The world of online advertising has changed dramatically since Ghostery first launched in 2009 to help people understand and block all the ways that advertisers were tracking them.

Since then, Ghostery and ad blocking at large have attracted a significant user base. (In Ghostery’s case, the company says it has been downloaded more than 100 million times, with 7 million people using the app or browser extension on a monthly basis.) At the same time, the major browsers have promised more privacy-friendly features, and the European Union even attempted to regulate the issue through legislation known as GDPR.

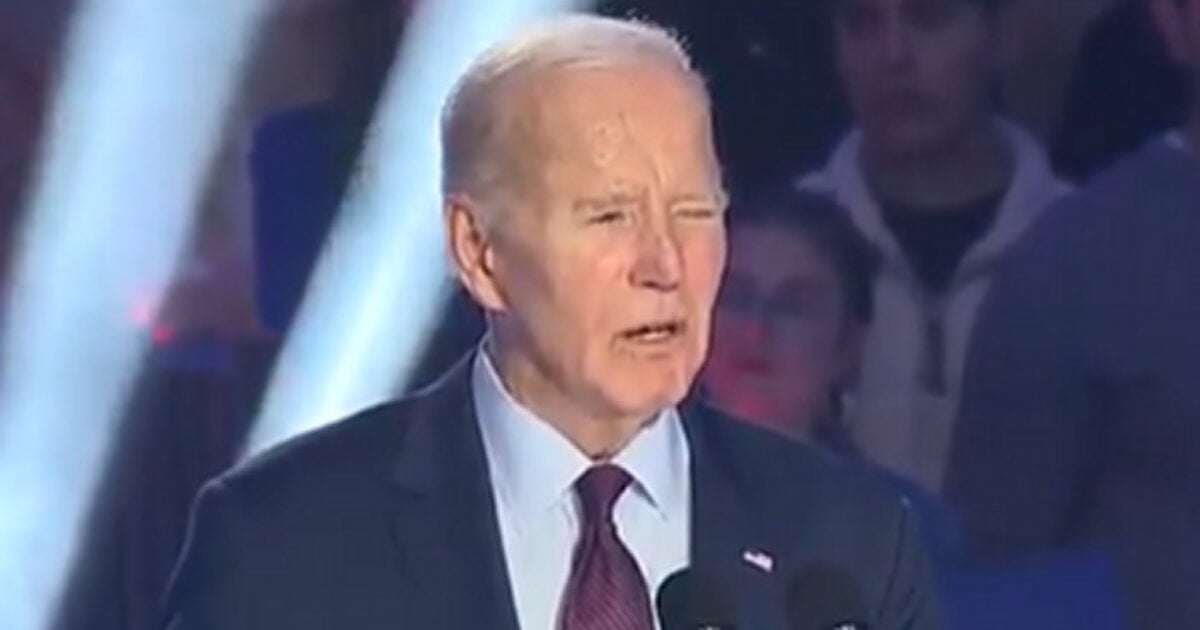

So with Ghostery turning 15 years old this month, TechCrunch caught up with CEO Jean-Paul Schmetz to discuss the company’s strategy, the state of ad tracking, and why he doesn’t believe regulation is the most effective path to protecting online privacy.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

We’re here to talk about 15 years of Ghostery. Maybe the best place to start is your own involvement: What’s your history with Ghostery?

I became deeply involved in 2016, so about halfway through the 15 years, when we acquired Ghostery.

If you go back to 2008 or 2009, it was really the time where the web started to change. Because before that, Google was a remarkably private company, it was just doing search, there was no huge industrial tracking to speak of. But Facebook was emerging with all kinds of social profiling, etc., etc., and a group of engineers, including myself at that time (I was more on the search side) began to notice that we didn’t really like the way our browser was being used to send signals invisibly to a bunch of third parties.

So what you start doing is, you start to just block [trackers], which basically is Ghostery, and many [other products] that emerge around that time. Then you notice that you get less ads, and then you notice that obviously, you don’t like ads too much, either. So you start blocking that. And eventually, over the last 15 years, it’s been an ever increasing trend in the industry to go towards more and more third-party [tracking], more and more and more things happening behind your back.

And when you say you bought Ghostery, that was through Cliqz, right?

Correct. Back then, Cliqz was a search engine. And we noticed that as an independent search engine, we needed the browser, because Google was not going to distribute us, Firefox was in bed with Google, Safari was in bed, basically everyone was in bed with Google, so we decided we needed to build a browser. And because of this history I just mentioned, we wanted a browser that would, out of the box, take care of the tracking and blocking, etc. That’s essentially how we became interested in acquiring Ghostery, to have that capability.

[The Cliqz search engine was subsequently acquired by privacy-focused browser Brave, which used the technology to launch a search engine of its own.] Is there still that idea of using the search engine and the browser together, using Brave and Ghostery together?

Now, Ghostery is an extension. So it has the advantage, for some people, that you can continue using the tools that you are used to. If you like Safari, you put Ghostery on top of it, if you like Chrome, you put Ghostery on top of it.

Brave is a lifestyle change. Both are equally good, I would argue, but we definitely have an easier time getting users, just because we are a very small decision, right? You just download the extension. You don’t have to change your password, your bookmarks — everything will continue working exactly as it was before.

When you look at Ghostery 10, we spent a lot of attention making sure that normal users have a good UI: It’s not too techie, it informs you a lot, and it pulls back if the web stops working for some reason. We spend a lot of time not assuming that our users are super techies who can figure things out, so we help them make the right decision to disable anti-tracking for the next five minutes.

More broadly, it sounds like you’re seeing the number of trackers just continue to increase?

Quantity has definitely increased, massively. There was a little bump, or a little fork in the road where GDPR came in, in Europe, where we noticed first a decrease, and then massive increase, as companies managed to figure out their consent layers and stuff like that.

At the moment, we’re noticing a shift towards first-party cookies versus third party, but that probably changed again [this week], when Google announced that they will not pull the third-party cookies after all.

It’s a bit unclear what happens [next], I actually believe that Google wants to [block third party cookies], but the publishers, the advertisers, the competition authority all went up in arms and said, “Wait a minute, if you do this, you will hurt my business.”

And Google [this week] announced that they would make it a choice for the user. That’s very interesting, because they don’t tell you if the choice is to turn on privacy or to turn it off. We will have to find out, but the problem is — and the reason why Ghostery continues to be super relevant — is that you just cannot trust Big Tech [or] regulation to come to your rescue.

I want to talk about both of those categories, Big Tech and regulation. You mentioned that with GDPR, there was a fork where there’s a little bit of a decrease in tracking, and then it went up again. Is that because companies realized they can just make people say yes and consent to tracking?

What happened is that in the U.S., it continued to grow, and in Europe, it went down massively. But then the companies started to get these consent layers done. And as they figured it out, the tracking went back up. Is there more tracking in the U.S. than there is in Europe? For sure.

So it had an impact, but it didn’t necessarily change the trajectory?

It had an impact, but it’s not sufficient. Because these constant layers are basically meant to trick you in saying yes. And then once you say yes, they never ask again, whereas if you say no, they keep asking. But luckily, if you say yes, and you have Ghostery installed, well, it doesn’t matter, because we block it anyway.

And then Big Tech has a huge advantage because they always get consent, right? If you cannot search for something in Google unless you click on the blue button, you’re going to give them access to all of your data, and you will need to rely on people like us to be able to clean that up.

So when it comes to Big Tech and their browsers, they also talk about taking additional steps against cookies and other kinds of tracking. Do you think they’ve made meaningful progress?

Safari did for sure at one point, and nearly destroyed Facebook’s business. But as you can see, Facebook rebounded, right? So they find ways, because the browsers themselves are afraid to go [all the way], because it does have an effect on breaking certain websites. As Ghostery, we can protect our users and be mindful of what they see. I don’t know how it is when you work for Safari, and you have a billion users or whatever they have, right? It’s a different ballgame. [Some reports have indeed placed Safari’s reach at more than 1 billion users.]

My feeling is that browsers will, by definition, be much slower than extensions. We can be at the forefront. But it is also clear that if we do something that actually works and that users absolutely want, browsers will eventually copy us.

Before we talked, I was trying to track down some numbers about ad blocker usage over the last decade or so. I don’t know if there’s anything definitive, but my sense is that growth has flattened over the last few years. Is that your sense as well?

We don’t really see it like that. When you ask people [if they use an ad blocker], the number that comes out is very, very high.

I mean, you’re getting into the deep mass market, so it is kind of normal that it flattens out, but the need for it is still the same, and the ease of use has become better, and [on more platforms]. For example, for a long time, it was impossible to use on mobile. And now it is actually possible to use it on Safari [on mobile]. So you can start to be so the usage is growing, if only by platform.

I’d also like to talk about YouTube, because that seems to be how ad blocking suddenly goes from a niche topic to something everyone’s talking about, whenever YouTube makes a change. The way I’ve heard it characterized is as an ongoing cat-and-mouse game between the ad blocking companies and YouTube. Is that just how it’s going to be for the foreseeable future?

The cat-and-mouse game, I believe, is a dangerous game to play for YouTube, because every time they do it, they piss off the users. That is consistently what we find in surveys, people notice what we do for them exactly in these moments. And they take us with them when they go from [one browser to another]. We are the only constant, let’s say. So yes, it is a cat-and-mouse game, but it’s not as easy as good guy or bad guy. Because it’s also about who is doing what for the user, and who the user tends to be quite attached to.

Whenever I speak to someone in ad blocking about how much tracking is going on, I start to wonder why so much of the internet economy is built this way. We’ve been talking about what you need to do as an individual to protect your personal privacy, but do you have any hope that this is going to lead to broader change?

Why is it like this? Because the prevalent business model of the internet has been, for the last 10 years, some kind of programmatic advertising that relies on collecting data on one side and monetizing it somewhere else. That’s the root cause. Now, the user could change that — if everyone tomorrow would start using Brave, programmatic advertising would die. And then publishers and advertisers would need to find another way to monetize, which is possible. Magazines make money, TV makes money without having all this tracking going on.

But if, let’s say 70% of the population does not protect themselves, programmatic advertising is so convenient for everyone involved. I don’t believe regulation can stop that, because the solution is always consent— which, unfortunately, Facebook and Google and Amazon will always get. I don’t think the authorities have the guts nor the will to say, “this is forbidden.” They’re going to try to attack it sideways, but not frontally.

So it’s really about users. The more users protect themselves, the more it becomes unsustainable. That’s the only vector of change that’s really possible.