Meanwhile, anti-encryption initiatives in the US, including proposed legislation like the Earn It Act, continue to pit law enforcement against technical protections. Pfefferkorn is clear about the divide. “You really can’t be pro-choice and anti-encryption at this point,” she says.

Researchers point out that encryption is often thought of in the context of enabling free speech, but it can also be looked at through the lens of self-defense.

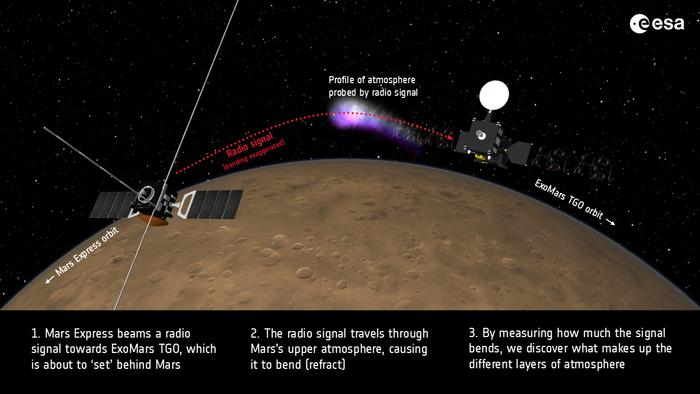

“Effective, uncensorable, secret communications are certainly far more valuable to resistance movements than small arms are,” says computer security consultant Ryan Lackey. “If you had magic, secure telepathy between everyone in your organization, in a civil war or resistance scenario where some of your allies were inside the opposition, you wouldn’t need a single gun to win.”

Lackey points out that there are parallels between encryption and firearms, as laid out in the Second Amendment, an observation that others have explored at times. The crucial element, though, is the connection to a right to self-defense, which the Supreme Court’s Second Amendment absolutists cite repeatedly as the law’s “central component.”

Beyond end-to-end encryption’s ability to protect people from their government, police, and prosecutors, it also protects them from other people who seek to enact harm, be they criminal hackers or violent extremists. While equating encryption to a weapon misconstrues its function—it’s much more shield than sword—these defenses remain the most powerful tool people everywhere have to protect their digital privacy. And a clear parallel can be drawn to the fervor with which gun advocates embrace their right to bear arms.

Stanford’s Pfefferkorn points out that it is logical and necessary for abortion providers, patients, or anyone who is pro-choice to embrace and defend encryption in general, but particularly so in light of the overturning of Roe v. Wade. She adds that in this moment, when the Supreme Court is reversing decades of established precedent on a variety of issues at once, the most important generalizable takeaway is the benefits of access to end-to-end encryption, and the necessity of preserving that access.

“Laws can change. Social rules can change. The perfectly harmless conversation you had yesterday might come back to hurt you years from now,” says Johns Hopkins cryptographer Matthew Green. “That’s why we don’t write down every spoken conversation and keep it forever. Encryption is just a way to give digital communications the same basic protections.”

Twenty-six states have either criminalized abortion, will do so, or are likely to take that step. How those laws will be enforced remains unknown. What’s certain is that millions of people who had nothing to hide before the Supreme Court’s June 24 decision now face the prospect of potential targeting, surveillance, and even prison over their reproductive health. And comprehensive encryption will be essential to their self-defense. As Signal’s Marlinspike said during a panel discussion at the 2016 RSA security conference in San Francisco, “I actually think that law enforcement should be difficult … I think it should actually be possible to break the law.”