I was first just reading about how MRIs have got really big magnets in them, and thinking: I know that the magnetic field extends out away from them. It can’t extend out forever, because when I drop my keys, they don’t go flying off to the nearest MRI.

So the first question is: How far out does that magnetic field go? That I could figure out by looking at MRI manuals. I was reading through these guides, and they were like: “If you have this kind of equipment, you need to put it this far away. And if you have this kind of equipment, it needs to be this far away. Here’s a diagram showing the zones around the machine where you shouldn’t have any magnetic tape equipment. You can’t have credit cards inside this distance.” And then it would mention that this far out, you might get interference with sensitive magnetic sensors.

That was neat, just realizing that in a hospital, you might have lots of different equipment, so there’s a whole complicated process for figuring out what can go how close to an MRI … and then I would just start Googling “helicopter MRI,” “MRI helicopter report,” trying to figure out: Has this ever come up? And then was sort of surprised to find that there was an incident report.

Is there anything recently that you’ve read that has really excited you, that you wish more people knew about?

I feel like all I am is a pile of facts that I’m excited to tell people about. There was a chapter on disintegrating a block of iron. Someone was like: “What if I vaporize a block of iron in my yard? What consequences does that have?”

I know that if you vaporize iron it’ll react with the oxygen in the air and form iron oxide, which will precipitate out into little particles that float around. But I don’t know what that does. Is that good? Is that bad?

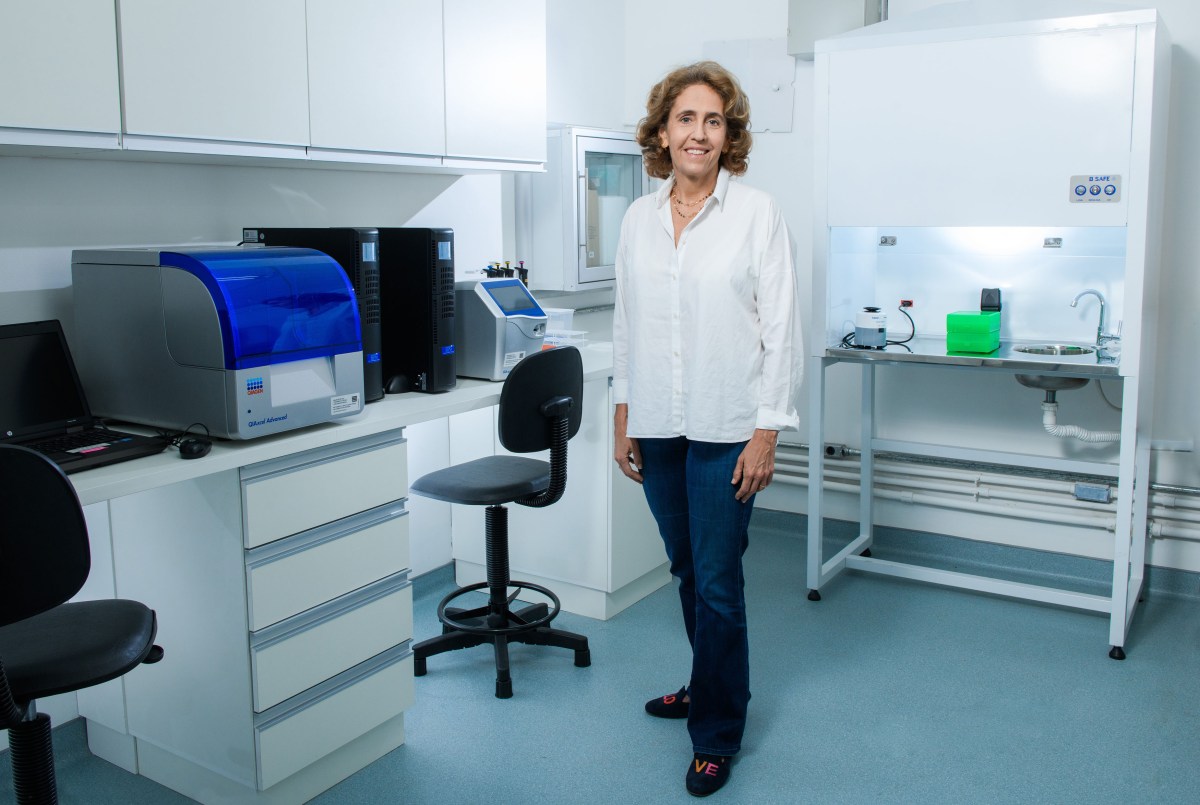

And so I ended up getting in touch with an expert in iron transport in the atmosphere, Natalie Mahowald, who worked on the IPCC Climate report. I asked: “Okay, what happens if you just inject a bunch of iron into the air?” Which turns out to be an interesting question that they’ve looked at for climate and ocean fertilization reasons. Something she said that stuck out was: “If you live downwind, and this iron vapor comes through and you breathe it, it’ll be bad for you.”

And I asked: “Is that because it’s a metal? Is it toxic? Is it bad for your lungs?”

She said something along the lines of: “It’s not that it’s a metal, it’s just that your lungs are supposed to breathe air. And there’s just not a lot of particulates you can breathe in that are good for you.”

Huh! It doesn’t really matter what it is. It’s just not air.

It’s funny how often that’s come up since then. We think of toxins, or we think about how these chemicals are bad for you, or these substances are bad for you. But ever since I saw it framed that way, I’ve realized how many different areas of life where the question of, “Are these small particles that you’re breathing in bad for you?” has, again and again, the answer of, “Anything that’s not air is not great for you.”

![[VIDEO] ‘Physical’ Season 2 Trailer, Release Date on Apple TV+ [VIDEO] ‘Physical’ Season 2 Trailer, Release Date on Apple TV+](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/physical-season-2-date.jpg?w=630)