In early 2021 emergency room physician Torree McGowan hoped the worst of the pandemic was behind her. She and her colleagues had adapted to the COVID-causing virus, donning layers of protection before seeing each patient, but they’d managed to keep things running smoothly. The central Oregon region where McGowan lived—a high desert plateau ringed by snow-capped mountains—had largely escaped the first COVID waves that slammed areas such as New York City.

Then the virus’s Delta variant hit central Oregon with exponential fury, and the delicate balance McGowan had maintained came crashing down. Suddenly, COVID patients were streaming into the ERs at the hospitals where she worked, and she had to tell many patients she was powerless to help them because the few drugs she had didn’t work in late stages of the disease. “That feels really terrible,” McGowan says. “That’s not what any of us signed up for.”

It wasn’t just COVID patients McGowan couldn’t help. It was also everyone else. People still approached a health-care emergency with the expectation that they were going to be taken care of right away. But in the midst of the surge, there were no beds. “And I don’t have a helicopter that can fly you between my hospital and the next hospital,” she says, “because they’re all full.” A patient with suspected colon cancer showed up bleeding in the ER, and McGowan’s inner impulses screamed that she needed to admit the woman immediately for testing. But because there were no beds left, she had to send the patient home instead.

The need to abandon her own standards and watch people suffer and die was hard enough for McGowan. Just as disorienting, though, was the sense that more and more patients no longer cared what happened to her or anyone else. She had assumed she and her patients played by the same basic rules—that she would try her utmost to help them get better and that they would support her or at least treat her humanely.

But as the virus extended its reach, those relationships broke down. Unvaccinated COVID patients walked into the exam room maskless, against hospital policy. They cursed her out for telling them they had the virus. “I have heard so many people say, ‘I don’t care if I make someone sick and kill them,’” McGowan says. Their ruthlessness simultaneously terrified and enraged her—not least because she had an immunocompromised husband at home. “Every month I do hours and hours of continuing education,” McGowan says. “Every patient that I’ve ever made a mistake on, I can tell you every bit about that. And the thought that people are so callous with a life, when I place so much value on somebody’s life—it’s a lot to carry.”

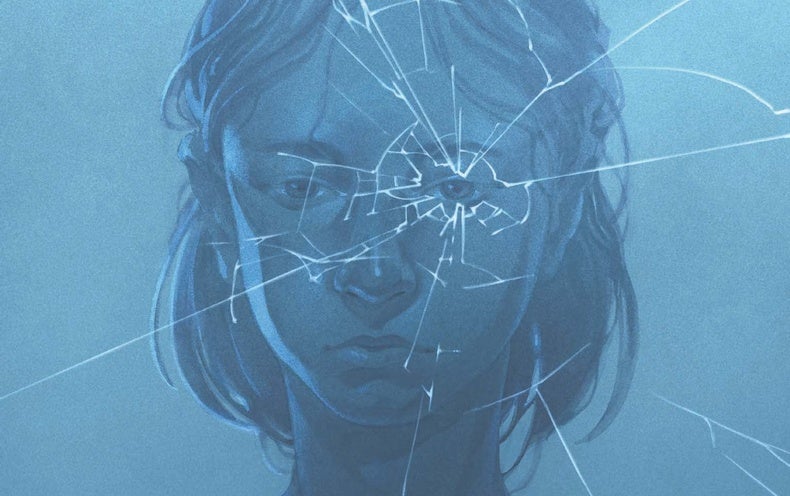

Moral injury is a specific trauma that arises when people face situations that deeply violate their conscience or threaten their core values. Those who grapple with it, such as McGowan, can struggle with guilt, anger and a consuming sense that they can’t forgive themselves or others.

The condition affects millions across many roles. In an atmosphere of rationed care, doctors must admit a few patients and turn many away. Soldiers kill civilians to complete assigned missions. Veterinarians must put animals down when no one steps up to adopt them.

The trauma is far more widespread and devastating than most people realize. “It’s really clear to us that it is all over the place,” says psychiatrist Wendy Dean, president and co-founder of the nonprofit Moral Injury of Healthcare in Carlisle, Pa. “It’s social workers, educators, lawyers.” Survey studies in the U.S. report that more than half of K–12 professionals, including teachers, moderately or strongly agree that they have faced morally injurious situations involving others. Similar studies in Europe show that about half of physicians have been exposed to potentially morally injurious events at high levels.

Even these figures may be artificially low, given scant public awareness of moral injury: many people do not yet have the vocabulary to describe what is happening to them. Whatever the exact numbers, the mental health effects are vast. In a King’s College London meta-analysis that surveyed 13 studies, moral injury predicted higher rates of depression and suicidal impulses.

When COVID swept the planet, the moral injury crisis became more pressing as ethically wrenching dilemmas became the new normal—not just for health-care workers but for others in frontline roles. Store employees had to risk their own safety and that of vulnerable family members to make a living. Lawyers often could not meet clients in person, making it nearly impossible to represent those clients adequately. In such situations, “no matter how hard you work, you’re always going to be falling short,” says California public defender Jenny Andrews.

Although moral injury doesn’t yet have its own listing in diagnostic manuals, there is a growing consensus that it is a condition that is distinct from depression or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This consensus has given rise to treatments that aim to help people resolve long-standing ethical traumas. These treatments—vital additions to a broad range of trauma therapies—encourage people to face moral conflicts head-on rather than blotting them out or explaining them away, and they emphasize the importance of community support in long-term recovery. In some cases, therapy clients even create plans to make amends for harms committed.

Even if moral injury research is a young and growing field, scientists and clinicians already agree that a key step toward healing for morally injured people—whether in therapy or not—has to do with grasping the true nature of what they’re facing. They’re not hopeless, “bad seeds” or uniquely irredeemable. They may not fit the criteria for PTSD or another mental illness. Instead they’re suffering from a severe disconnect between the moral principles they live by and the reality of what is happening or has happened. In moral injury, “that sense of who you are as a person has been brought into question,” Dean says. “We have a lot of people saying, ‘This is the language I’ve been looking for for the past 20 years.’”

Ancient Origins

Although VA psychiatrist Jonathan Shay coined the term “moral injury” in the 1990s, the phenomenon predates its naming by millennia. In the ancient Greek epic The Iliad, the hero Achilles loses his best friend Patroclus in battle and then inwardly tortures himself because he failed to shield Patroclus from harm. When world wars broke out in the 20th century, people labeled as “battle fatigued” the returning soldiers who bore mental scars. In reality, many of them were tortured not by shell shock but by wartime deeds they felt too ashamed to recount. In the 1980s University of Nebraska Medical Center ethicist Andrew Jameton observed that this kind of moral distress was not confined to the military realm. It often “arises when one knows the right thing to do,” he wrote, “but constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action.”

What spurred the first rigorous study of moral injury, however, was the multitude of U.S. soldiers struggling after serving in wars in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan. Psychologist Brett Litz of the Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System saw quite a few vets of these conflicts who weren’t responding well to counseling after their deployments ended. They seemed to be stuck in stagnant grief over acts they’d committed, such as killing civilians in war zones. They reminded Litz of one of his past therapists who’d seemed oddly detached, never mentally present in the room. Afterward Litz found out why. “Probably months before I went to him, he had opened his car door, and he killed a child who was just biking down the road,” Litz says. “He was as broken as can be. I witnessed firsthand what that was.”

In long conversations with veterans, Litz grew convinced he was witnessing a condition that was different from PTSD and depression. PTSD typically takes root when someone’s life or safety is threatened. But much of the lingering trauma Litz saw in vets had nothing to do with direct personal threat. It was related to mounting guilt and hopelessness, “the totality of the inhumanity, the lack of meaning and the participation in grotesque war things,” he says. “They were pariahs—or felt that way, at least.”

Building on Shay’s earlier work, Litz resolved to develop a working concept of moral injury so that researchers could study it in depth and figure out how best to treat it. “I thought, ‘This is going to affect our culture, and there are going to be broad impacts,’” he says. “We needed to bring science to bear. We needed to define the terms.”

To that end, Litz and his colleagues published a comprehensive paper on moral injury in 2009, outlining common moral struggles veterans were facing and proposing a treatment approach that involved making personally meaningful reparations for harm done. He noted, too, that not all “potentially morally injurious events” cause moral injury. If you kill someone, and you feel totally justified in having done so, you may not experience moral injury at all. Moral injury tends to turn up when you have a vision of the world as fundamentally fair and good and something you’ve done or witnessed destroys that vision.

Litz’s paper soon caught the attention of Rita Nakashima Brock, then a visiting scholar at Starr King School for the Ministry in California. A theologian and antiwar activist, Brock was preparing to convene the Truth Commission on Conscience in War, an event where returned soldiers would testify about the moral impact of engaging in battle.

Brock’s antiwar activism had personal roots. After her father, a U.S. Army medic, returned from Vietnam, he withdrew from his family. When he did speak to his loved ones, he lashed out with an escalating rage. “My dad was so different that I didn’t even want to be at home anymore,” she says. After Brock’s father died, she pieced together more of his story with a cousin’s help. He had worked with a guide while deployed, a young Vietnamese woman who was later tortured and killed. He was horrified at what had happened—and likely also racked with guilt because he knew his ties to the guide could have put her in danger.

As soon as Brock saw Litz’s moral injury paper, something clicked. “When my colleague and I read it, we said, ‘Oh, my God, this is what the whole thing is about,’” she recalls. “We sent it to everybody testifying and said, ‘Read this.’”

Chronicling the Unspeakable

After Brock’s 2010 Truth Commission, her committee set forth a key objective: creating programs to inform the public about moral injury. With a grant from the private Lilly Endowment, Brock established a moral injury research and education program at Texas’s Brite Divinity School. Later Tommy Potter—then a development officer at Brite—mentioned Brock’s work to his childhood friend Mike King, CEO of the national nonprofit Volunteers of America (VOA), and Brock and King arranged a time to meet.

VOA had long focused on helping marginalized populations, and when Brock described the moral injury concept to King, “it just instantly resonated with every area of our work,” King says. “It is profoundly there with veterans. But I could see it in our work with folks coming out of incarceration and certainly with health care.” So in 2017 VOA put up about $1.3 million in funding to create the Shay Moral Injury Center in Alexandria, Va., named for Jonathan Shay. Brock became the center’s first director, heading up research and training programs aimed at understanding and treating moral injury.

Meanwhile moral injury research at Litz’s lab and elsewhere was starting to take flight. In 2013, along with his health-care colleagues, Litz debuted and road tested what he called the Moral Injury Events Scale, a measure of exposure to events that can cause moral injury. The scale assessed things such as how much people felt they’d violated their morals, how much they felt others had betrayed important values and the level of distress they experienced as a result. Other investigators have confirmed moral injury can come with significant mental health burdens: in a 2019 study of five VA clinics across the U.S., people who’d experienced moral injury consistently had a higher risk of suicide than control participants.

Other research also backs up Litz’s initial hunch that moral injury is distinct from PTSD, although the two conditions sometimes overlap. A 2019 study by researchers at the Salisbury VA Healthcare System in North Carolina reports that moral injury has different brain signatures than for PTSD alone: People with moral injury have more activity in the brain’s precuneus area, which helps to govern moral judgments, than those who only have PTSD. And after people suffer moral traumas, they display different brain glucose metabolism patterns than those who suffer direct physical threats, according to a 2016 study by researchers at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and their colleagues. The results support developing theories that moral injury is a unique biological entity.

As Brock’s Shay Moral Injury Center was being established, she forged connections with powerful people who could get the word out about moral injury—including Margaret Kibben, the current chaplain at the U.S. House of Representatives. Kibben holds regular events for House members, and one of her recent talks was about moral injury. The event drew about three times more members than usual, Brock reports, “and they all wanted to talk about their experience.” Brock and Kibben’s partnership reflects a growing trend in the study of moral injury: collaboration between scholars and clergy members who aim to chronicle the unspeakable and to help people through it. Moral injury “does really bring together a lot of disciplines,” says psychologist Anna Harwood-Gross of Metiv, the Israel Psychotrauma Center in Jerusalem. “It’s rare to see articles written by chaplains and psychologists together.”

As COVID ravaged the planet from 2020 onward, moral injury research and inquiry took a distinct new turn. Health-care workers spoke out about how rationing care was affecting them psychologically, and Dean and her colleagues Breanne Jacobs and Rita Manfredi, both at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, published a journal article that urged employers to monitor moral injury’s effects. “We need time, energy and intellectual capacity to make peace with those specters,” they wrote.

The moral injury Dean sees in health care often doesn’t stem from one-time, cataclysmic events. Many providers are suffering what she calls “death by a thousand cuts”—the constant, stultifying knowledge that they have to give people subpar care or none at all. “They think they suck. They think they’re inadequate,” says trauma surgeon Gregory Peck of New Jersey’s Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. “No one’s putting their finger on ‘You don’t suck. This is moral injury you’re suffering.’” Psychiatrist Mona Masood, who founded the Physician Support Line in 2020, has heard countless doctors agonize over daily moral compromises. “We’ll hear, ‘Am I really a failure? Have I failed my calling? Am I something not human anymore?’”

Off-Axis

Those words would surely resonate with McGowan. During an increase in COVID cases, as we approach a hospital where she works regular shifts, an ambulance pulls out of the parking lot, lights flashing, underneath looming clouds. “That’s probably another transfer,” McGowan says. Someone, in other words, has claimed one of the few available COVID beds in the region, meaning someone else—someone just as sick—may have to do without. Inside the ER, a bare-bones suite of rooms and hallways, glove boxes and black cords dangle from the walls. As we walk around, we spot warning signs of other moral compromises ahead. A scrawled note on a hallway whiteboard reads, “Critical shortage of green top tubes. 0-day supply of blue tops.” When these tubes run out, McGowan explains, she may not be able to order blood tests patients need—and, as a result, may have a hard time figuring out what’s wrong with them.

On many days during the pandemic, McGowan has struggled with the dislocation of shuttling between the ER—a personal hell of COVID deniers, irate family members and dying patients—and the outside world, which feels disturbingly normal. How, she wonders, can people nonchalantly chat and sip coffee when, minutes before, she sent someone home who could barely breathe? How can her own moral world be knocked so profoundly off-axis while the larger world continues to spin with scarcely a wobble?

McGowan sees a therapist to help her process the situations she’s faced, which she says has been helpful. Yet she continues to grapple with the fallout of moral dilemmas, reflecting a growing consensus that traditional therapy may not always be enough to help morally injured people get past lingering demons. Those who seek help sometimes make headway with basic cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), the current gold standard among insurers. Some researchers think CBT approaches are sufficient to treat moral injury.

But one sticking point with CBT is that it focuses on correcting clients’ distorted thought patterns. For people with moral injury who’ve experienced wrenching events that upend their entire value system, ethical distress is genuine, not the product of distorted thinking, Harwood-Gross says. If people with moral injury simply try to retrain their thoughts, they may be left unsatisfied and unhealed.

Therapies for PTSD can likewise fall short for morally injured patients, in Harwood-Gross’s experience. PTSD-focused approaches teach clients to adapt to traumatic triggers, such as fireworks that sound like gunshots, but this exposure approach doesn’t really help them resolve deep ethical conflicts. Effective moral injury counseling is “more about the processing,” Harwood-Gross says. “There has to be that movement: ‘How do I see it for what it is and, from there, develop something more meaningful?’ It’s a more spiritual approach.”

Recognizing moral injury’s unique challenges, psychologists such as Litz have been creating therapies that more directly address clients’ needs. Litz and other providers have pioneered a moral injury treatment called adaptive disclosure. Researchers at Australia’s La Trobe University and University of Queensland have developed a similar approach called pastoral narrative disclosure. The latter involves discussing moral issues with a chaplain or other spiritual adviser rather than a doctor.

These therapies stress the importance of moral reckoning. They encourage clients to accept uncomfortable truths: “I led that attack on Iraqi civilians”; “I sent that suffering patient home without treatment.” Then, with clients’ input, counselors can help them develop strategies for making amends or pursuing closure—say, apologizing to a family whose child they injured.

Early evidence suggests these approaches make headway where others can’t. In Litz’s initial trial of adaptive disclosure on 44 marines, participants’ negative beliefs about both themselves and the world diminished. Most also said the therapy helped to resolve their moral dilemmas.

Earlier this year Litz wrapped up a 173-person clinical trial of adaptive disclosure at VA sites in Boston, Minneapolis, San Diego, San Francisco and central Texas. The trial’s results have not yet been published, but Litz found that, in general, adaptive disclosure boosted participants’ level of functioning over time. Litz says his goal is not to wipe people’s moral slates clean but to restore their ability to thrive. “You’ll never not feel awful when you think about what happened,” Litz adds. “That’s going to be the new normal. The question is ‘How do you rehabilitate and live a good-enough life?’”

For Brock’s VOA team, moral injury rehabilitation also involves a suite of peer-support programs. The Shay Moral Injury Center’s core group offering, Resilience Strength Training (RST), is a 60-hour, in-person program where people with moral injury share stories about events that caused it, engage in talks about forgiveness (for themselves or others), and do exercises to help them define their value system and purpose going forward. In a survey study at two VOA program sites, participants scored an average of 46 percent higher on a scale of post-traumatic growth and 19 percent higher on a scale of perceived meaning in life than they had before starting the program. Although the in-person program paused during the pandemic, plans to restart it are currently underway.

In 2020 VOA created an online version of RST for health workers and others called Resilience Strength Time (ReST). Free ReST sessions run a few times a week, and attendees sign up for as many as they want.

During a recent ReST video meeting, several people showed up to talk for an hour about their moral challenges on the health-care front lines. One spoke about feeling helpless as she watched a patient verbally abuse a nurse giving vaccines. Peer-session leaders Bruce Gonseth and Jim Wong, both war vets, listened closely to each attendee’s dilemma and empathized, often sharing recollections of similar situations they had faced. “To me, what we experienced in the war was exactly what frontline workers are experiencing: the invisible enemy,” Wong told the group. “You may feel like you’re letting other people down. You may observe others engaging in harmful behaviors. You’re not alone. We’re here to support you.”

In most therapeutic relationships, a power differential exists between therapist and client. VOA’s groups, where members and facilitators take turns being vulnerable, put participants on a more even footing. This openness builds bonds that support people’s recovery, ensuring their moral struggles won’t isolate them. “These are people who know them well and intimately, and it matters,” Brock says. “Moral injury is a relationship break—you have an identity crisis. You have to establish new relationships that sustain you.”

Therapies addressing moral injury that bolster clients’ sense of purpose share a common goal with treatments developed by Austrian psychologist Viktor Frankl, who believed that a personal search for meaning could fuel trauma recovery. To survive his imprisonment in Nazi camps, including Auschwitz, Frankl focused on what motivated him to go on—his boundless love for his wife, his commitment to rewrite a research manuscript the Nazis had destroyed. “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing,” Frankl wrote, “the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.” After his liberation in 1945, Frankl refined a treatment approach called logotherapy, which emphasized that a sense of purpose could help people endure the gravest suffering.

As Frankl would have done, therapists such as Litz and Harwood-Gross encourage clients to accept the depth of inhumanity in the world rather than attempt to blot out awareness of that inhumanity. The essential question—the same one Frankl confronted—then becomes: “In the midst of what has happened and what is still happening, how can I find meaning in life?”

Partnerships between clinicians and religious leaders have helped facilitate that search for meaning, Brock says. Mental health treatment can feel like a formalized setup in which “the role of the professional is not to be personal,“ she says. But clergy often excel at connecting on a more informal, human level—an asset in dealing with morally injured people who have come to doubt their own humanity. “Chaplains don’t bill by the hour,” Brock says. “They spend the time they need to spend with people.”

No Easy Way Out

Moral injury treatments are a needed safety valve for people battling guilt and ethical vertigo. Even so, as old hands on the front lines note, nudging the morally injured toward self-repair goes only so far. Therapy can help you move on from past choices, but unless your employer hires more staff or supplies more resources, chances are you’ll have to keep making decisions that violate your ethics, compounding your trauma. A lot of problems that cause moral injury “require systemic solutions on a much broader level,” says Andrews, the California public defender.

Yet many organizations are taking the easy way out, Dean says. Instead of launching systemic reforms that could help head off moral injury, they’re offering “wellness solutions” such as massages and meditation tips, which can amount to putting a Band-Aid on a broken bone. “If I have to listen to another ‘eat well, sleep well, do yoga’ conversation, I’m going to throw up,” says New York City ER doctor Jane Kim. What would be better, she thinks, is in-depth, system-wide conversations about what frontline workers actually need to do their jobs ethically, not what outside wellness providers assume they need. She argues that reforms based on these frank internal assessments would benefit both workers and those they serve. “We care for other people,” she says. “But if we are broken ourselves, how can we possibly help others?”

As the pandemic drags on, similar thoughts occupy McGowan’s mind. Although COVID hospital admissions have decreased somewhat in her area, workers have been quitting in droves, which means there still aren’t enough providers to give patients adequate treatment. “I compare it to the Bataan Death March. There’s no end in sight,” McGowan says. On a bookshelf in her light-filled farmhouse, a plaque reads, “You never know how strong you are until being strong is the only choice you have.”

The windows overlook a parched expanse of field—McGowan’s farmer husband grew just a fraction of his usual hay crop last year because of a drought. In some ways, they face the same existential dilemma: What do you do when forces beyond your control shrivel your highest intentions?

To counter thoughts of hopelessness, of failing her medical calling, McGowan tries to focus on specific acts of good she’s been able to perform. When she’s not in the ER, she serves as a lieutenant colonel in the Oregon Air National Guard, and her unit has vaccinated more than 100,000 people against COVID.

Mentoring other doctors, too—offering advice as they process the same kinds of harrowing choices and regrets she’s had—has buoyed her. “That’s helped me learn to be a little bit kinder to myself,” McGowan says. “The same words that I tell them, I try to repeat to myself: You did the best that you could.” She inhales, hesitating. “And you are still a good doctor. I would still let you take care of my family.”