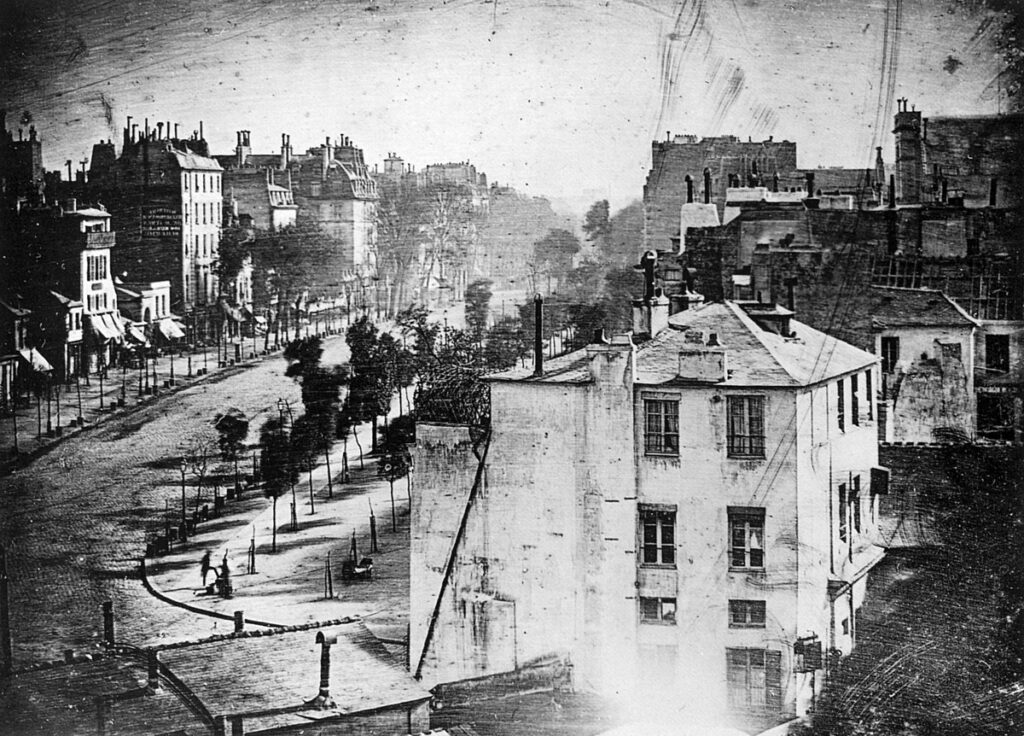

More shadows than men, really; just silhouettes, might as well be smudges on the lens. Hard to notice at first, the two undifferentiated figures in the lower left-hand of the picture, at the corner of the Boulevard du Temple. A bootblack squats down and shines the shoes of a man contrapasso above him; impossible to tell what they’re wearing or what they look like. Obviously no way to ascertain their names or professions. At first they’re hard to recognize as people, these whispers of a figure joined together, eternally preserved by silver-plated copper and mercury vapor; they’re insignificant next to the buildings, elegant Beaux-Arts shops and theaters, wrought iron railings along the streets and chimneys on their mansard roofs. Based on an analysis of the light, Louis Daguerre set up his camera around eight in the morning; leaves are still on trees, so it’s not winter, but otherwise it’s hard to tell what season it is that Paris day in 1838. Whatever their names, it was by accident that they became the first two humans to be photographed.

“I have seized the light,” Daguerre supposedly said. “I have arrested its flight!” About six by five inches of metal were polished to a sheen, all traces of detritus burned away with nitric acid, placed into the plate holder opposite from a lens placed into a wooden box, treated with iodine fumes, and exposed to heated mercury until an alchemical miasma reproduced a Paris morning. The boulevard should have been filled with people, busy rushing to work or purchasing groceries, perhaps stopping for pan de chocolate, and yet the street is silent, everything quiet except for these two men unified in anonymity. Such quietude is illusory, for when Daguerre set up his mechanism, no doubt the boulevard was filled with people. Yet their existence was too wispy to ever be recorded, the exposure being at least eight minutes long. Unknown to the photographer, only the bootblack and his customer stood still long enough to be observed by eternity. There are some who claim they see a child looking out of a window, or a horse standing stationary on the boulevard. Like most of us, just ghosts in a vacuum.

In the beginning there may have been the Word, but several millennia later there was the Image. The two most revolutionary technological advances in human consciousness are the invention of writing and then the ability to record life as-it-is in the form of photography and sound recording. Neither Guttenberg‘s printing press or Alan Turing‘s computer come close in importance. At best they extended those earlier revolutions, but ultimately print and digital were just means of disseminating words and images more efficiently. When Daguerre unveiled Boulevard du Temple at the Academy of Fine Arts and Academy of Sciences in 1839, it was as if delivered by angels. Reflecting in 1859 on how surprising the invention was, Oliver Wendell Holmes claimed in The Atlantic Monthly that “in all the prophecies of dreaming enthusiasts, in all the random guesses of the future conquests over matter, we do not remember any prediction of such inconceivable wonder.” As a statement there are aspects of this that are both true and false—Daguerre drew on several different technical innovations, some which went back centuries, and other methods were simultaneously developed. Yet by the time Boulevard du Temple was exhibited it must have seemed like a miraculous surprise, for as Mary Warner Marien writes in Photography: A Cultural History, “Unlike other transformational technologies such as air travel and automobile, photography was not foreseen in the centuries before it was invented.”

In the beginning there may have been the Word, but several millennia later there was the Image. The two most revolutionary technological advances in human consciousness are the invention of writing and then the ability to record life as-it-is in the form of photography and sound recording. Neither Guttenberg‘s printing press or Alan Turing‘s computer come close in importance. At best they extended those earlier revolutions, but ultimately print and digital were just means of disseminating words and images more efficiently. When Daguerre unveiled Boulevard du Temple at the Academy of Fine Arts and Academy of Sciences in 1839, it was as if delivered by angels. Reflecting in 1859 on how surprising the invention was, Oliver Wendell Holmes claimed in The Atlantic Monthly that “in all the prophecies of dreaming enthusiasts, in all the random guesses of the future conquests over matter, we do not remember any prediction of such inconceivable wonder.” As a statement there are aspects of this that are both true and false—Daguerre drew on several different technical innovations, some which went back centuries, and other methods were simultaneously developed. Yet by the time Boulevard du Temple was exhibited it must have seemed like a miraculous surprise, for as Mary Warner Marien writes in Photography: A Cultural History, “Unlike other transformational technologies such as air travel and automobile, photography was not foreseen in the centuries before it was invented.”

While unforeseen, the technical reasons for why the annus mirabilis for photography was 1838 are befuddling, because theoretically it’s conceivable that it could have been invented far earlier. Daguerre combined two different processes. The first was the optical effect known as “camera obscura,” whereby a lens can focus an upside down image onto a wall, and the second was the fact that there are certain chemicals which are sensitive to light. Camera obscuras were first written about by the Chinese philosopher Mozi four centuries before the Common Era, and explored by dozens of others, including Aristotle and Leonardo da Vinci, with the latter having noted in the Codex Atlanticus that “If the façade of a building, or a place, or a landscape is illuminated by the sun and a small hole is drilled in the wall of a room […] which is not directly lighted by the sun, then all objects illuminated […] will send their images through this aperture and will appear, upside down, on the wall facing the hole.” Renaissance painters would avail themselves of the effect to more accurately trace pictures onto canvases.

Regarding light-sensitive substances, as early as 1717 the German chemist Johann Heinrich Schulze used a combination of exposed silver, nitric acid, and chalk to make outlines of letters that could be considered the first “photographs,” even while their life-span was but a few minutes. Nor was Daguerre the only person working on the problem; notably, there was Edward Fox Talbot‘s almost simultaneously developed method of reproducing images on paper, which would eventually supplant the metal plates of the daguerreotype. Also invaluable to Daguerre’s work was Nicéphore Niépce, whom the former readily credited, and who took the first photograph of anything in 1826, View from the Window of Le Gras, which required an exposure of several days. Examining View from the Window of Le Gras, it’s difficult to see what’s significant; it looks like nothing. As Robert Hirsch writes in Seizing the Light: A Social and Aesthetic History of Photography, the “camera was not designed as a radical device to unleash a new way of seeing,” but as “with most inventions, unforeseen side effects create unintentional changes.” At the very least Daguerre understood what he was offering—not just representation, or artifice, or even mimesis. His invention, he wrote, was “not merely an instrument which serves to draw Nature; on the contrary it is a physical and chemical process which gives her the power to reproduce herself.” Photography gave reality itself the ability to self-generate.

Regarding light-sensitive substances, as early as 1717 the German chemist Johann Heinrich Schulze used a combination of exposed silver, nitric acid, and chalk to make outlines of letters that could be considered the first “photographs,” even while their life-span was but a few minutes. Nor was Daguerre the only person working on the problem; notably, there was Edward Fox Talbot‘s almost simultaneously developed method of reproducing images on paper, which would eventually supplant the metal plates of the daguerreotype. Also invaluable to Daguerre’s work was Nicéphore Niépce, whom the former readily credited, and who took the first photograph of anything in 1826, View from the Window of Le Gras, which required an exposure of several days. Examining View from the Window of Le Gras, it’s difficult to see what’s significant; it looks like nothing. As Robert Hirsch writes in Seizing the Light: A Social and Aesthetic History of Photography, the “camera was not designed as a radical device to unleash a new way of seeing,” but as “with most inventions, unforeseen side effects create unintentional changes.” At the very least Daguerre understood what he was offering—not just representation, or artifice, or even mimesis. His invention, he wrote, was “not merely an instrument which serves to draw Nature; on the contrary it is a physical and chemical process which gives her the power to reproduce herself.” Photography gave reality itself the ability to self-generate.

Audio preservation was accomplished by Daguerre’s fellow countryman Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville (exactly two decades before Thomas Edison) with his invention of the phonautograph, meant to visually transcribe sound waves onto a bit of sooty paper. By 1877, the phonograph cylinder as produced by Edison would actually allow for playable recordings, and by 1894 the inventor would open one of the first film studios that produced sequential celluloid photographs that would be rapidly projected to simulate the effect of motion. By the time director Alan Crosland had effectively merged moving image and sound with the first full-length “talkie” movie, The Jazz Singer, in 1927, the revolution in consciousness had reached its culmination. Now humanity had the ability to present reality in a way that we never had before. Everything that has happened since has merely been an adaptation of that idea, even if in the technical particulars have immeasurably improved. It was the most radical change in how we viewed existence since Mesopotamian scribes first pushed wedged letters into baked tablets made of clay from the Euphrates.

Four years before Boulevard du Temple, Paul-Louis Robert wrote in The Journal of Artists that Daguerre was working on a procedure whereby “a portrait, a landscape, or any view […] leaves an imprint in light and shade, and thus presents the most perfect of all drawings [preserved] for an indefinite time.” Enthusiasts for the new medium, once it became widespread after the French government bought the patent in exchange for Daguerre’s life-time pension and then released the technology for free into the world, wrongly claimed that it would make painting redundant. But where photography does do something unique is in collapsing distance and time so as to present the immediacy of a present that has since moved on; it gives the appearance of reality. Susan Sontag writes in On Photography that the form “is the reality; the real object is often experienced as a letdown.” As soon as photography was invented, trick photography followed, but such hoaxing is only so successful because the original form was so powerful. You’re only apt to believe the lie because photography appears so trustworthy. By contrast, painting offered something different and irreplaceable, where the artifice was always embedded in the experience, even while photography gifted something novel. When Caravaggio depicts Judith’s sword garroting into the sinews of Holofernes’s neck, the picture is more sublime than reality; Rembrandt‘s black-bedecked gentleman present a gauzy tableau that feels like midnight as much as it looks like it. What Boulevard du Temple offers is exactly what somebody would see if looking out that window in Paris. That’s why they’re both sublime.

Four years before Boulevard du Temple, Paul-Louis Robert wrote in The Journal of Artists that Daguerre was working on a procedure whereby “a portrait, a landscape, or any view […] leaves an imprint in light and shade, and thus presents the most perfect of all drawings [preserved] for an indefinite time.” Enthusiasts for the new medium, once it became widespread after the French government bought the patent in exchange for Daguerre’s life-time pension and then released the technology for free into the world, wrongly claimed that it would make painting redundant. But where photography does do something unique is in collapsing distance and time so as to present the immediacy of a present that has since moved on; it gives the appearance of reality. Susan Sontag writes in On Photography that the form “is the reality; the real object is often experienced as a letdown.” As soon as photography was invented, trick photography followed, but such hoaxing is only so successful because the original form was so powerful. You’re only apt to believe the lie because photography appears so trustworthy. By contrast, painting offered something different and irreplaceable, where the artifice was always embedded in the experience, even while photography gifted something novel. When Caravaggio depicts Judith’s sword garroting into the sinews of Holofernes’s neck, the picture is more sublime than reality; Rembrandt‘s black-bedecked gentleman present a gauzy tableau that feels like midnight as much as it looks like it. What Boulevard du Temple offers is exactly what somebody would see if looking out that window in Paris. That’s why they’re both sublime.

Daguerre’s method was supplanted by quicker, simpler, and more accurate ways of preserving an image. What Daguerre gifted us was a significant development in consciousness, which allowed anyone to record themselves or what they seen or who they love and to transmit that experience to others. At an 1861 address, Frederick Douglass—among the most photographed men in America at the time—said that “Daguerre, by simply but all abounding sunlight has converted the planet into a picture gallery[.…] Daguerreotypes, Ambrotypes, Photographs and Electrotypes, good and bad, now adorn or disfigure all our dwellings[.…] What was once the exclusive luxury of the rich and great is now within reach of all.” Working class people flocked to studios to have their images preserved, seeing in the process the equivalent of an affordable portrait; abolitionists used it to record the horrors of slavery and to capture the dignity of Black Americans; war correspondents conveyed the barbarity of battle. Paul Valery writes in Alan Trachtenberg‘s anthology Classic Essays on Photography that “man’s way of seeing began to change, and even his way of living felt the repercussions of the novelty […] creating new needs and hitherto unimagined customs.” Improvement was swift. Talbot introduced paper photographs; by 1884 George Eastman patented dry gel paper or film, and four years later his Kodak Corporation camera allowed for amateurs to take pictures that would be developed by others. Color photography, Polaroid photography, digital photography, social media all followed. Ours is a post-Daguerre world. Our vision is in photographs, our perspective is in photographs, our memories are in photographs. In the last two minutes the cumulative number of pictures taken—uploaded to Facebook and Instagram, sent in emails and texts—surpasses the number of photographs from the entirety of the nineteenth-century. Since that anonymous bootblack and his customer had their portraits shot, there have been an astounding 3.5 trillion photographs taken.

Daguerre’s method was supplanted by quicker, simpler, and more accurate ways of preserving an image. What Daguerre gifted us was a significant development in consciousness, which allowed anyone to record themselves or what they seen or who they love and to transmit that experience to others. At an 1861 address, Frederick Douglass—among the most photographed men in America at the time—said that “Daguerre, by simply but all abounding sunlight has converted the planet into a picture gallery[.…] Daguerreotypes, Ambrotypes, Photographs and Electrotypes, good and bad, now adorn or disfigure all our dwellings[.…] What was once the exclusive luxury of the rich and great is now within reach of all.” Working class people flocked to studios to have their images preserved, seeing in the process the equivalent of an affordable portrait; abolitionists used it to record the horrors of slavery and to capture the dignity of Black Americans; war correspondents conveyed the barbarity of battle. Paul Valery writes in Alan Trachtenberg‘s anthology Classic Essays on Photography that “man’s way of seeing began to change, and even his way of living felt the repercussions of the novelty […] creating new needs and hitherto unimagined customs.” Improvement was swift. Talbot introduced paper photographs; by 1884 George Eastman patented dry gel paper or film, and four years later his Kodak Corporation camera allowed for amateurs to take pictures that would be developed by others. Color photography, Polaroid photography, digital photography, social media all followed. Ours is a post-Daguerre world. Our vision is in photographs, our perspective is in photographs, our memories are in photographs. In the last two minutes the cumulative number of pictures taken—uploaded to Facebook and Instagram, sent in emails and texts—surpasses the number of photographs from the entirety of the nineteenth-century. Since that anonymous bootblack and his customer had their portraits shot, there have been an astounding 3.5 trillion photographs taken.

The invention of photography, less than 200 years old, seems both strangely recent and perilously distant. 1839 is an impenetrable barrier, as the entirety of human history before then was filtered through the descriptions of writers or the imaginations of artists, but in the exact particulars of what somebody looked like, the experience of an event, the sense of a place, the details themselves are forever hidden behind a veil. So new is photography that there are the figures whom we almost could have seen rendered in metal and chemical—Benjamin Franklin, Jane Austen, Napoleon Bonaparte—all just slightly beyond that horizon. Sontag writes that if given the choice between Hans Holbein having lived long enough to paint Shakespeare, or the camera having been invented early enough to capture an image, most of those who worship the playwright would opt for the latter, for even if the “photograph were faded, barely legible, a brownish shadow, we would probably still prefer it[.…] Having a photograph of Shakespeare would be like having a nail from the True Cross.”

Photographs can be artful and they can be amateurish, they can be accurate and they can be misleading, they can be redemptive and they can be demeaning, but what they supply is an unmediated present. This is not an insignificant thing. “Down Wall, from girder into street noon leaks,” writes poet Hart Crane about Brooklyn Bridge, describing how “A rip-tooth of the sky’s acetylene; / All afternoon the cloud flown derricks turn[…] / Thy cables breathe the North Atlantic still.” Crane is doing many things, all of them masterful. He is conjuring a deeper understanding, incanting a mystic sense of the Brooklyn Bridge. He is perhaps obliquely describing it. But if you can imagine what the Brooklyn Bridge looks like while reading Crane, it’s undoubtedly because you’ve seen a photo before. If all you had to go on was Crane’s description, you’d never get it right. Albert Camus in his American Diaries wrote of the Manhattan skyline that “Sometimes from beyond the skyscrapers, across thousands of high walls, the fearful cry of a too-well-known voice finds you in your insomnia in the middle of the night, and you remember that this desert of iron and cement is an island of un-reality.” It’s evocative, it’s beautiful, it’s certainly true, but Camus writes in poetry, not in images (as anyone working with words must). When he describes New York as a “desert of iron and cement,” it’s a spiritually true assertion, and you can probably see in your mind the art deco golem of the Chrysler Building, the behemoth of the Empire State, the leviathan of Rockefeller Center, but you’ve first seen them as photographs. If you can envision Manhattan, and you’ve never been there, then it’s because of a picture, not because of anything Camus wrote.

Photographs can be artful and they can be amateurish, they can be accurate and they can be misleading, they can be redemptive and they can be demeaning, but what they supply is an unmediated present. This is not an insignificant thing. “Down Wall, from girder into street noon leaks,” writes poet Hart Crane about Brooklyn Bridge, describing how “A rip-tooth of the sky’s acetylene; / All afternoon the cloud flown derricks turn[…] / Thy cables breathe the North Atlantic still.” Crane is doing many things, all of them masterful. He is conjuring a deeper understanding, incanting a mystic sense of the Brooklyn Bridge. He is perhaps obliquely describing it. But if you can imagine what the Brooklyn Bridge looks like while reading Crane, it’s undoubtedly because you’ve seen a photo before. If all you had to go on was Crane’s description, you’d never get it right. Albert Camus in his American Diaries wrote of the Manhattan skyline that “Sometimes from beyond the skyscrapers, across thousands of high walls, the fearful cry of a too-well-known voice finds you in your insomnia in the middle of the night, and you remember that this desert of iron and cement is an island of un-reality.” It’s evocative, it’s beautiful, it’s certainly true, but Camus writes in poetry, not in images (as anyone working with words must). When he describes New York as a “desert of iron and cement,” it’s a spiritually true assertion, and you can probably see in your mind the art deco golem of the Chrysler Building, the behemoth of the Empire State, the leviathan of Rockefeller Center, but you’ve first seen them as photographs. If you can envision Manhattan, and you’ve never been there, then it’s because of a picture, not because of anything Camus wrote.

Those aren’t dings on Crane or Camus—far from it. No writer could provide the complete and utter texture of description which a photograph accomplishes, at least not without gruelingly slow exposition, which fortunately isn’t the purpose of writing. Chaucer can’t drop you into Canterbury nor can Cervantes into Andalusia—that was never their intent. But photography can—the form democratized experience because it collapses those distinctions of space and time. The medium would never replace writing or painting because it did something new. At the same time, and precisely because of that “something new,” writing and painting are irrevocably altered, our experience can’t be the same as those who read before Daguerre. Chaucer and Cervantes might not bring to mind an exact image of Canterbury and Andalusia, but they do for us, and that difference is technological. “Photography mirrored the external world automatically, yielding an exactly repeatable visual image,” writes Marshall McLuhan in Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. “It was this all important quality of uniformity and repeatability that had made the Gutenberg break between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance”—and then again between what came before Daguerre and afterwards. McLuhan underscores that it’s more than just verisimilitude that makes photography different (though it is that). It’s also replicability. Any argument that photography wasn’t so radical because painting was already capable of conveying reality ignores that most people weren’t privy to Caravaggios or Rembrandts (at least not until they could see photographs of them), and though there were means of producing images (woodcuts, lithographs, engravings, mezzotint) the realism of the medium differentiates it. Unequivocally this would alter perspective, would shift consciousness, and it’s obvious in both art and literature. Walter Benjamin writes in his 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” that the “amazing growth of our techniques, the adaptability and precision that have attained, the ideas and habits they are creating, make it a certainty that profound changes are impending the ancient craft of the Beautiful […] neither matter nor space nor time has been what it was from time immemorial.” The result of photography and sound recording was that we became new, post-Daguerre humans.

Those aren’t dings on Crane or Camus—far from it. No writer could provide the complete and utter texture of description which a photograph accomplishes, at least not without gruelingly slow exposition, which fortunately isn’t the purpose of writing. Chaucer can’t drop you into Canterbury nor can Cervantes into Andalusia—that was never their intent. But photography can—the form democratized experience because it collapses those distinctions of space and time. The medium would never replace writing or painting because it did something new. At the same time, and precisely because of that “something new,” writing and painting are irrevocably altered, our experience can’t be the same as those who read before Daguerre. Chaucer and Cervantes might not bring to mind an exact image of Canterbury and Andalusia, but they do for us, and that difference is technological. “Photography mirrored the external world automatically, yielding an exactly repeatable visual image,” writes Marshall McLuhan in Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. “It was this all important quality of uniformity and repeatability that had made the Gutenberg break between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance”—and then again between what came before Daguerre and afterwards. McLuhan underscores that it’s more than just verisimilitude that makes photography different (though it is that). It’s also replicability. Any argument that photography wasn’t so radical because painting was already capable of conveying reality ignores that most people weren’t privy to Caravaggios or Rembrandts (at least not until they could see photographs of them), and though there were means of producing images (woodcuts, lithographs, engravings, mezzotint) the realism of the medium differentiates it. Unequivocally this would alter perspective, would shift consciousness, and it’s obvious in both art and literature. Walter Benjamin writes in his 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” that the “amazing growth of our techniques, the adaptability and precision that have attained, the ideas and habits they are creating, make it a certainty that profound changes are impending the ancient craft of the Beautiful […] neither matter nor space nor time has been what it was from time immemorial.” The result of photography and sound recording was that we became new, post-Daguerre humans.

Painters reacted to the rise of the photograph by embracing abstraction. Impressionism, with its consideration of color and light, proceeds from photography. For all of the stereotypical carping about how modern art lacks technique, the ability to produce paintings that are indistinguishable from reality awaited artists like Richard Estes, Audrey Flack, Ron Kleeman, John Baeder, Tom Blackwell, and Chuck Close, who are conveniently labeled “photorealists.” Meanwhile literary modernism, with its attraction towards fragmentation, bricolage, and multiple perspectives, resembled an assemblage of photographs hanging on a gallery wall, with the poetic embrace towards lyric an acknowledgement that each picture is as if a poem. Because Western chauvinism has largely resisted the integration of word and image, canonical novels which integrate photography is surprisingly slim. Virginia Woolf‘s 1928 novel Orlando included a photograph of her lover Vita Sackville-West as the gender bending titular character. W.G. Sebald included pictures in his novels The Emigrants, Rings of Saturn, and Austerlitz, writing in that last title that “It seems to me then as if all the moments of our life occupy the same space,” a succinct description of the post-Daguerre world. Poets, perhaps because they already worked in a form that is episodic and crystalline, embraced the new technology more fully. Dadaist artist Man Ray and poet Paul Eluard produced a volume that combined both in Facile, while more current titles include Lisa Scalapino‘s Crowd and Not Evening or Light and poet Ian Thomas‘s and photographer Jon Ellis‘s I Wrote This for You.

Then there are photography books, which are not just adornment for coffee tables but literature. In Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, the writer James Agee and photographer Walker Evans travelled Depression-era United States, recording stoicism and poverty, resolve and degradation. Alabama sharecroppers with faces as ragged as the red soil, determined laborers with tired eyes staring at the camera as if Medieval icons, families with bare feet and dirty fingernails huddled in front of dilapidated wooden shacks, all marshaled to demonstrate that “next to unassisted and weaponless consciousness,” the camera is the “central instrument of our time.” Nan Goldin used the camera on a different subject, if based in similar principles, in her 1986 book The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. Chronicling her own experiences in New York with transients and junkies, queers and sex workers, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is an honest and unabashed account of existence among the marginalized, as true as anything in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. “There is a popular notion, that the photography is by nature a voyeur,” Goldin writes, “but I’m not crashing; this is my party. This is my family, my history.” From the very beginning photographers were drawn to celebrity, glamor, and elegance, a natural manifestation of aristocratic portraiture, and Annie Leibovitz has both embodied and subverted that purpose. A radiant, pregnant Demi Moore cradling her belly in the nude on the cover of Vanity Fair and appearing as if the Virgin Mary; Yoko Ono in jeans and a black turtleneck, embraced by a naked John Lennon clutching to her in a fetal position; a beautiful, young Leonardo DiCaprio in black with a white swan cradled around his neck. Flipping through Annie Leibovitz Portraits: 2005-2016, we’re apt to agree with the artist’s lover Sontag who wrote, “So successful has been the camera’s role in beautifying the world that photographs, rather than the world, have become the standard of the beautiful.”

Then there are photography books, which are not just adornment for coffee tables but literature. In Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, the writer James Agee and photographer Walker Evans travelled Depression-era United States, recording stoicism and poverty, resolve and degradation. Alabama sharecroppers with faces as ragged as the red soil, determined laborers with tired eyes staring at the camera as if Medieval icons, families with bare feet and dirty fingernails huddled in front of dilapidated wooden shacks, all marshaled to demonstrate that “next to unassisted and weaponless consciousness,” the camera is the “central instrument of our time.” Nan Goldin used the camera on a different subject, if based in similar principles, in her 1986 book The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. Chronicling her own experiences in New York with transients and junkies, queers and sex workers, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is an honest and unabashed account of existence among the marginalized, as true as anything in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. “There is a popular notion, that the photography is by nature a voyeur,” Goldin writes, “but I’m not crashing; this is my party. This is my family, my history.” From the very beginning photographers were drawn to celebrity, glamor, and elegance, a natural manifestation of aristocratic portraiture, and Annie Leibovitz has both embodied and subverted that purpose. A radiant, pregnant Demi Moore cradling her belly in the nude on the cover of Vanity Fair and appearing as if the Virgin Mary; Yoko Ono in jeans and a black turtleneck, embraced by a naked John Lennon clutching to her in a fetal position; a beautiful, young Leonardo DiCaprio in black with a white swan cradled around his neck. Flipping through Annie Leibovitz Portraits: 2005-2016, we’re apt to agree with the artist’s lover Sontag who wrote, “So successful has been the camera’s role in beautifying the world that photographs, rather than the world, have become the standard of the beautiful.”

A perfect photograph is a lyric poem. It gestures towards narrative, but does not spell it out; it relishes in detail, but is not didactic; it’s as in love with the granularity of beach wood or the smoothness of a mirror as much as it is with any abstraction. How much more incomplete would our love of Abraham Lincoln be if the camera had been invented later? Only 130 photographs of Lincoln exist—there are many more pictures of my dog in existence than there are of the sixteenth president. He sat for any number of photographers, including several times for the nineteenth century’s greatest master of the daguerreotype, Matthew Brady, and yet it’s Alexander Gardner’s 1863 picture that most fully exemplifies Lincoln. Walt Whitman described Lincoln, whom he loved to the point of idolatry, as “crooked-legged, stoop-shouldered” and with “anything but a handsome face,” a visage so distinctive and “so awful ugly it becomes beautiful.” When painted, Lincoln appears at best homely. But Gardner’s photograph conveys the awesome weight of Whitman’s observation. The granitoid face, the hawkish nose, the warm and exhausted eyes, the ring of prophetic beard and the springy, parted hair, the lined forehead and high cheekbones, the deep fissures and wrinkles that appear as if the landscape of the fractured country itself. Very different commitments are on display in a photograph from Leni Riefenstahl‘s 1973 book The Last of the Nuba, commensurate with Benjamin’s observation that the “logical result of Fascism is the introduction of aesthetics into political life.” Without biographical context, such an observation could at first seem surprising when applied to Riefenstahl’s consummately well-done photograph. A Sudanese warrior stands shirtless, toned, muscular, and powerful, two geometrical scarification tattoos about his pectorals; he stares away at the camera, not disturbed by it so much as indifferent. In another picture, a warrior with white face paint sits staring down, a wooden staff in his hand. In a third photograph, Riefenstahl captures two nude fighters in the midst of a ritual wrestling match, expressions hardened in rage, muscles tense and arms poised to strike.

The figures in Riefenstahl’s lens are gorgeous, women and men who are physically perfect, with the photographer purposefully contrasting the darkness of their skin against the brightness of the Sudanese sun. Riefenstahl also neglects to capture any of the inner life of these people, treating them as props, an assemblage of mechanisms that demonstrate the human body’s athleticism. “Although the Nuba are black, not Aryan, Riefenstahl’s portrait of them is consistent with some of the larger themes of Nazi ideology,” argued Sontag in a controversial essay in The New York Review of Books. Analyzing how Riefenstahl reduced the Nuba into “Noble Savages,” Sontag also observes the way in which the photographer enshrines strength over weakness, purity over corruption, power over infirmity, beauty over ugliness, simplicity over complexity. Perhaps all of this would have been interpreted as over-interpretation were it not that Riefenstahl had been the most celebrated of Nazi propaganda filmmakers, depicting Adolf Hitler as a messianic figure in movies like Olympia and Triumph of the Will, technical masterpieces completely devoid of anything that could be called basic human feeling.

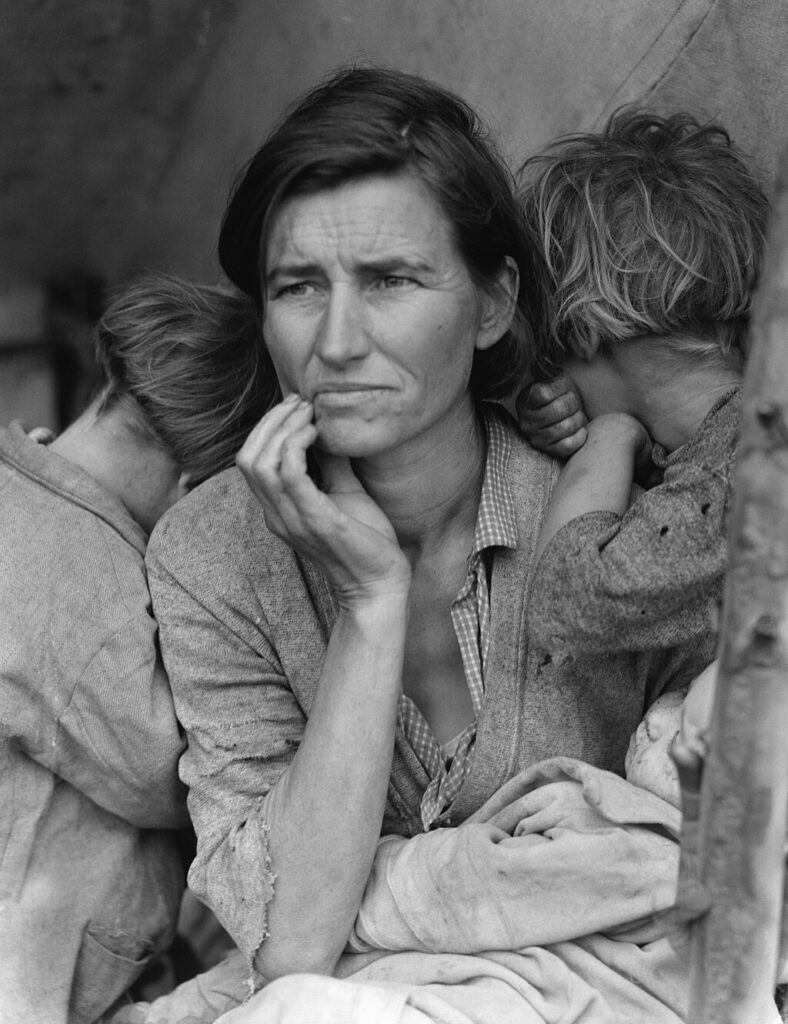

At the same time that Riefenstahl was filming Hitler emerging in a prop plane like a conquering Valkyrie, the photojournalist Dorothea Lange was traversing the United States with funding from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt‘s Farm Security Administration. Traveling through rural California, Lange chronicled the effects of the Dust Bowl, particularly among those internal refugees disparagingly called “Okies.” By far her most recognizable picture is Migrant Mother, a portrait of the itinerant farmer Florence Owens Thompson shot in 1936. Of partial Cherokee ancestry, the Oklahoma-born Thompson had migrated to Bakersfield, California, to work, picking upwards of 500 pounds of cotton a day, and later laboring in the beet fields near Imperial Valley. Lang recalled in Popular Photography, “I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet…[she] seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.” Thompson is exhausted, dust-caked, weary-eyed. Her children crowd around behind her, faces away from the camera, like angels whom it’s impossible to look directly towards. The woman looks worried, the only emotion that perhaps competes with her exhaustion. In their brief exchange, Thompson told Lang that the family was surviving on vegetables frozen in the field and dead birds her children found. Unlike Riefenstahl’s subjects, Lang preserves the core of humanity in Thompson. A sadness not dissimilar to Gardner’s conjuration of Lincoln, a deep and abiding sense of embodied pain.

A few decades later, Diane Arbus would capture a less divine picture of childhood in her faintly disturbing Child with Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park. Taken in 1962, Arbus’s photograph is of a skinny, tow-headed young boy in overalls who would be the prototypical example of all-American wholesomeness were it not for the toy weapon he holds with a claw-like grip, and the maniacal, vacant, slightly-demonic expression on his face. The boy’s figure seems dark, even while he stands in a light speckled bit of pavement, benches in the background, a canopy of trees overhead. Drawn to the seamier side of American mid-century life—circus geeks and strippers, weight lifters and drag performers—Arbus highlighted degenerate enchantment. Like Goldin after her, she was attracted to that which normative society discarded. Nominally, the child in this photograph is perhaps not as extreme as some of Arbus’ other subjects, and yet his expression, his posture, his slightly nefarious goofiness – the boy is obviously a misfit, an odd-ball, an outsider, a weirdo. Colin Wood, the boy in the picture, recalled years later to The Washington Post that Arbus had caught “me in a moment of exasperation. It’s true, I was exasperated […] there was a general feeling of loneliness, a sense of being abandoned. I was just exploding. She saw that and it’s like […] commiseration. She captured the loneliness of everyone.”

Another misfit was the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, who like Arbus would find in New York his great arcade of human experience, millions of human poems. Most notoriously identified with the BDSM images he produced, which merited attacks by Republican congressmen over his receiving a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, Mapplethorpe was also an exporter of downtown effortless cool. Associated with sadomasochistic and homoerotic images—gigantic exposed cocks, bullwhips in anuses—Mapplethorpe also turned his lens to celebrity, producing iconic images of Iggy Pop, Andy Warhol, Philip Glass, and Patti Smith. The latter had been his former lover and lifelong friend, and Mapplethorpe enshrined Smith on the cover of her debut album Horses. As rendered by Mapplethorpe, the punk-poet is an apotheosis of androgynous beauty. In black jeans and white button up with a jacket confidently slung over her shoulder, strangely evoking a young Frank Sinatra, Smith reverses the scopophilia that marks Western depictions of femininity —she looks back at you. As Smith writes in Just Kids, a memoir of her and Mapplethorpe’s life together, “Robert took areas of dark human consent and made them into art [.…] Without affectation, he created a presence that was wholly male without sacrificing feminine grace.”

Another misfit was the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, who like Arbus would find in New York his great arcade of human experience, millions of human poems. Most notoriously identified with the BDSM images he produced, which merited attacks by Republican congressmen over his receiving a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, Mapplethorpe was also an exporter of downtown effortless cool. Associated with sadomasochistic and homoerotic images—gigantic exposed cocks, bullwhips in anuses—Mapplethorpe also turned his lens to celebrity, producing iconic images of Iggy Pop, Andy Warhol, Philip Glass, and Patti Smith. The latter had been his former lover and lifelong friend, and Mapplethorpe enshrined Smith on the cover of her debut album Horses. As rendered by Mapplethorpe, the punk-poet is an apotheosis of androgynous beauty. In black jeans and white button up with a jacket confidently slung over her shoulder, strangely evoking a young Frank Sinatra, Smith reverses the scopophilia that marks Western depictions of femininity —she looks back at you. As Smith writes in Just Kids, a memoir of her and Mapplethorpe’s life together, “Robert took areas of dark human consent and made them into art [.…] Without affectation, he created a presence that was wholly male without sacrificing feminine grace.”

By being able to bottle an impromptu second, photography is able to do something which only automatic writing or jazz improvisation did before. Such an art can show Truth—or a truth—in a manner unforeseen. Aesthetician John Berger writes in Understanding a Photograph that “most photographs taken of people are about suffering, and most of that suffering is manmade.” Gardner’s pile of bodies near a wooden fence in Antietam, Maryland, impossible to tell the color of their uniforms, in 1863. David Jackson‘s 1955 photograph of Emmett Till in his open casket, his face beaten to something inhuman, while his parents look at the camera with sadness inconceivable. Eddie Adams in Saigon, 1968, preserving the terrified look on Viet Cong captain Nguyen Van Lem‘s face in the seconds before South Vietnamese Brigadier General Nguyen Ngoc Loan fired his pistol into Lem’s head. John Paul Filo‘s shot of a Kent State University student at a protest, face down and dead, a friend next to the body screaming in 1970. Nick Ut‘s 1972 photo of nine-year-old Phan Thi Kim Phuc running naked outside of Trang Bang village after the South Vietnamese Airforce had dropped napalm on the civilian settlement. Jeff Widener‘s picture of a solitary, still anonymous man stopping a line of tanks in Tiananmen Square in 1989. Therese Frare‘s picture from 1990 of an emaciated, Christ-like David Kirby dying from AIDS, cradled as if a pieta by his grieving father. Richard Drew‘s 2001 image of a man falling from the collapsing World Trade Center, legs contrapasso just like the anonymous bootjack from Daguerre’s first photograph. U.S. Army Sergeant Ivan Frederick, both observer and perpetrator, snapping an anonymous Iraqi man in conical hood with arms outstretched during a torture session at Abu Ghraib prison in 2003. What each of these photographs capture is invaluable; they show the moment of grief, of tragedy, or desperation, of horror. They do something that millions of words in the Pentagon Papers or the 9/11 Report could never do. They speak the ineffable, they depict the inexplicable. Barger writes that photography derives not from “form, but […] time,” for the medium “bears witness to a human choice being exercised.” By collapsing space and time, photography made horror, sadness, hatred, despair present. But it could also capture love, it could transmit intimacy, joy, ecstasy across those same fathoms. For just as the instantaneous display of cruelty or anger or fear could be recorded, so too was it now possible for unmediated bliss to be preserved.

By being able to bottle an impromptu second, photography is able to do something which only automatic writing or jazz improvisation did before. Such an art can show Truth—or a truth—in a manner unforeseen. Aesthetician John Berger writes in Understanding a Photograph that “most photographs taken of people are about suffering, and most of that suffering is manmade.” Gardner’s pile of bodies near a wooden fence in Antietam, Maryland, impossible to tell the color of their uniforms, in 1863. David Jackson‘s 1955 photograph of Emmett Till in his open casket, his face beaten to something inhuman, while his parents look at the camera with sadness inconceivable. Eddie Adams in Saigon, 1968, preserving the terrified look on Viet Cong captain Nguyen Van Lem‘s face in the seconds before South Vietnamese Brigadier General Nguyen Ngoc Loan fired his pistol into Lem’s head. John Paul Filo‘s shot of a Kent State University student at a protest, face down and dead, a friend next to the body screaming in 1970. Nick Ut‘s 1972 photo of nine-year-old Phan Thi Kim Phuc running naked outside of Trang Bang village after the South Vietnamese Airforce had dropped napalm on the civilian settlement. Jeff Widener‘s picture of a solitary, still anonymous man stopping a line of tanks in Tiananmen Square in 1989. Therese Frare‘s picture from 1990 of an emaciated, Christ-like David Kirby dying from AIDS, cradled as if a pieta by his grieving father. Richard Drew‘s 2001 image of a man falling from the collapsing World Trade Center, legs contrapasso just like the anonymous bootjack from Daguerre’s first photograph. U.S. Army Sergeant Ivan Frederick, both observer and perpetrator, snapping an anonymous Iraqi man in conical hood with arms outstretched during a torture session at Abu Ghraib prison in 2003. What each of these photographs capture is invaluable; they show the moment of grief, of tragedy, or desperation, of horror. They do something that millions of words in the Pentagon Papers or the 9/11 Report could never do. They speak the ineffable, they depict the inexplicable. Barger writes that photography derives not from “form, but […] time,” for the medium “bears witness to a human choice being exercised.” By collapsing space and time, photography made horror, sadness, hatred, despair present. But it could also capture love, it could transmit intimacy, joy, ecstasy across those same fathoms. For just as the instantaneous display of cruelty or anger or fear could be recorded, so too was it now possible for unmediated bliss to be preserved.

Not shadows at all, really; but a couple. Hard not to notice, the woman and the man—she’s in a smart jacket and navy skirt, he’s dapper in a vest and suit—leaning against the 1940 Cadillac of photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris. Sometimes known as “One Shot” for his ability to capture the perfect photograph almost instantly, Harris was employed by The Pittsburgh Courier, the nation’s largest Black newspaper, where he chronicled life in the Hill District. The couple are young, beautiful, and in love, for the look that they give each other could be replicated by only the most talented of painters, her leaning against the shiny black steel of Harris’s car parked on Centre Avenue, a line of brick storefronts with canvas awnings behind them, the twinkle of a Coca Cola sign in one shop’s window. Imagine Harris returning with film back to his studio, setting up the baths of water, dimezone, sodium hydroxide, acetic acid, ammonium thiosulfate, shrouded in the uncanny red light of the darkroom. Moving photo paper back and forth from pools of liquid, and there as emerging from the firmament, like reality from chaos, coalesces the Cadillac, and the storefronts, and the shop’s sign, and the handsome couple from outside, their smiles coming from a nothing into an everything, as if light itself had been seized.