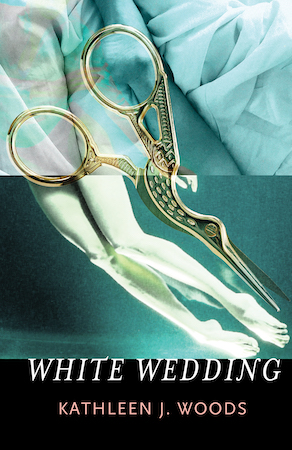

Porn and weddings: two of America’s most beloved forms of sexual fantasy. The former imagines a world where the fucking is both constant and constantly good, while the latter plays out a virginity pageant in which the indelicate deed doesn’t happen at all until marriage. Whether the fetish gear of choice is a white dress or a leather harness, our thirsts for both kinds of wet dream show no signs of abating. COVID sent internet pornography use through the roof as horny people the world over sheltered in place, while the gradual lifting of those same home confinement rules a few months later has positioned 2022 to be the most prolific year in four decades for American nuptials.

Kathleen J. Woods’s novella White Wedding is a psychedelic marriage of these two species of erotic reverie. A nameless woman arrives at a mountainside wedding, uninvited, and serially seduces anyone in her path, from the father of the bride to the caterer. Meanwhile, we slowly learn about the woman’s prior work in a pleasure mansion in the woods, where she fulfilled other women’s highly particular desires. Magic blurs with queer smut and kink as the woman seems to intuit exactly what each of her marks wants in their filthiest, softest heart of hearts—even if they don’t yet know they want it. She would also know exactly what you want. Can you imagine anything hotter? Can you imagine anything more terrifying?

Indeed, those darker body genres, horror and fairytale, are also at play in Woods’s erotica—and they don’t always play nice. From a tender fisting scene on a playground slide to a taxi driver who takes an unusual interest in his fares’ hookup habits, the fantasies in White Wedding push just as hard on the bounds of propriety as they do on those of literary genre. Woods’s interlinked tales are refreshing in their refusal to frame sex either as morally degrading or as intrinsically liberating. In a year when the rights of women, queer, and trans people undergo fresh assaults every week—legal attacks on abortion and on trans children’s access to gender-affirming care being just two recent instances thereof—White Wedding frankly asserts our rights to sex, freedom, and power.

Chelsea Davis: What attracts you to writing porn, as a genre?

Kathleen J. Woods: The pornographic mode was appealing to me because of its potential to not just be academically unsettling or philosophically unsettling, but to be viscerally unsettling to the reader. To enact confusion at the bodily level of the reader; to engage them in a way so that their senses are actually engaged and immersed; to make them discomfited by their own responses to what they’re reading. And also to give them some feeling of being out of reality.

When I was working on White Wedding, I found very useful a book called The Feminist Porn Book, which gives the following definition of feminist porn: “using sexually explicit imagery to contest and complicate dominant representations of gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity, class ability, age, body types, and other identity markers. It explores concepts of desire, agency, power, beauty, and pleasure at their most confounding and difficult.” I’ve found this definition to be guiding because it’s quite broad: it doesn’t lay out a specific way that feminist porn must appear, but is instead interested in an unsettling of normative standards of sexuality and in asking probing questions.

CD: Speaking of normative standards of sexuality: as we speak, it’s been less than a week since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. Has your book assumed any new significance for you since that court decision?

KW: The writing of the book happened over about seven years. Some of my initial impulses to write about a woman who is divorced from a past but who embodies sexual desire—those came from a world that already had a lot of misogyny and suspicion of overt sexuality. The election of Trump, and the #MeToo movement becoming really widespread, for example; those happened during the writing of the book. So the book already contains cathartic expressions of my anger in response to those events.

But the book has also remained a constant touchstone for me, of trying to ask, “What is a feminine sexuality, a queer sexuality, that isn’t a response to the harms of what the world does to us?” That’s not a question I think is answerable, for myself, outside of fiction.

CD: I think one of the ways your book answers that question is to depict scenes of non-mainstream sexuality with great detail and tenderness. But because of that intense detail (and I don’t say this with any moral judgment, of course), some of the book’s more intense edgeplay scenes were squirm-inducing for me, personally, to read. There’s a scene in the pleasure mansion where the woman pierces a lady’s back with small metal hoops, and another where the woman does a sounding act on the bride’s father, penetrating his urethra.

KW: It wasn’t out of a desire for shock value that I wrote those scenes. I was instead thinking about the different modes of the erotic. Feminine desire (and I’m going to continue using the word “feminine,” here, even acknowledging its limitations as a blanket term) to me does often seem like it centers on fantasies outside of the typical penetrative act. That is, feminine desire is not just for penis-in-vagina sex, which has so often been used to define sex in our Judeo-Christian culture, beginning with the concept of “virginity.”

With the corseting scene, I was also thinking about all the ways in which performing the feminine involves alteration of the body—how there can be a horror in that. So I included a shaving scene and a piercing scene. And it’s not just any back piercing that takes place; it’s a series of piercings in the shape of a corset. Today, corsets evoke a desire for the forbidden: we have more or less concluded that the corsetry of the past was painful and unnecessary for women—yet corseting remains a big part of contemporary kink, as does extreme body modification.

In writing that scene I wanted to make the medium of language as visceral as it would be if you were watching it in a movie or experiencing it in real life. Such that you want it to let up, you want relief—the same way that the girl who’s being corseted by the woman does. Using all five senses in those scenes was important to me, in order to have that penetrated effect on the reader.

CD: Of the five senses, smell is the sense that the reader gains the most access to in this book. On the one hand, there are the odors that accumulate on the woman’s body over the course of her repeated sex acts. But then there are also the odors that she’s constantly noticing in the world, from mulch to fabric softener. I thought your choice to focus on scent was fascinating because it’s so often a collective open secret that sex has a smell, or smells, associated with it. We all know it, yet much erotica doesn’t talk about it beyond a cursory nod to “musk.” I was curious why you chose to deviate from the pornographic norm in that way.

What is a feminine sexuality, a queer sexuality, that isn’t a response to the harms of what the world does to us?

KW: Smell seems to me like one of our most animalistic senses. And we don’t have very much control over our reactions to it—over whether we’re excited by a smell or revolted by it. Smell enters us, penetrates us.

It’s also a sense that the form of fiction, versus a painting or a film, has a unique ability to capture. I mean, I’ve definitely seen smell evoked in film. But it still seems like something that the page had a particular advantage in approaching.

CD: Much of your book takes place in a mysterious pleasure mansion in the woods, where women come to have erotic desires of all stripes fulfilled by the woman in a private room. Elsewhere, you’ve noted that the pleasure mansion is a recurring setting in erotic fiction and film, from Pauline Réage’s novel The Story of O to the video for Beyoncé’s song “Haunted.” We could also add the music video for “WAP” to that list. What do you think is so appealing about the pleasure mansion as a structure of sexual fantasy, perhaps even especially (since those creators I’ve just named are all women) of female erotic fantasy?

KW: There’s something that I find personally true about the vision of desire as a hallway of doors, in which what is behind them is suspected, but unknown. And your own response to what’s behind the doors is also both suspected and unknown. You move through this mysterious space with the agency of movement, with the agency of opening the door, with the agency of walking through and deciding to enter or look into a room—but also with a lack of agency in the sense that you have no control over what’s going to be behind that door.

You see this in so many stories about female curiosity, right? Eros and Psyche; Bluebeard’s wife; Pandora. It feels like an image that comes from our cultural makeup around women’s desire. There’s the thrill of the closed door and the long stretching hallway of what could be there. What could I find, and will it delight me? Will it hurt me? Will it condemn me?

CD: In some ways your book is itself structured like a pleasure mansion itself. The novella consists of a series of interpolated stories, like a hallway of doors each with private fantasies behind them. A character will describe a sexual encounter they’ve had in the past (or perhaps one they would’ve liked to have), which will then infect the listening character with lust, the desire to recall her own real or imagined sex scene. Why did you choose to arrange the book this way, with even more of an emphasis on erotic storytelling than on real-time sex scenes?

KW: One of the themes I was reflecting on a lot as I was approaching this book was the narratives we hear about sex—how we form our own story of what desire should be and what sex looks like through a bunch of different sources. We hear snippets of conversation; there are stories that we inherit from reading books and watching movies; and there are also the stories that we are told by figures in our life. It’s very confusing: you get a lot of contrasting stories. So the storytelling form itself is in question here—how true any of these stories that the Woman tells are.

I also wanted the book to have that feeling of an unsettling of time, of temporality being hazy and a little confused. Because I also think that is part of what is so potentially sometimes liberatory and terrifying about sexual pleasure is that, in moments of orgasm or pleasure, you’re often removed from and out of time. You are fully in the present in a way that is not true (for me, at least) a lot of the time out in the world. You get to exist without a past, without a future for a brief second (or a brief few seconds, or hours, depending on—you know—exactly what’s going on).

As in, you can briefly think, “I still have rights!” Although it’s not a perfect trick. Even during sex recently, “Roe v. Wade” has flashed through my brain.

CD: So even if sex can potentially create a sort of floating shell around you, sometimes the outside world still intrudes.

KW: Yeah. And I think sometimes that intrusive world is from those stories that we hear throughout our lives, too. As in, “I shouldn’t be doing this.” Or “I should hide this part of my body.”

CD: One of my favorite sequences in the book is a four-part Russian nesting doll of stories about just that—how body image concerns can intrude upon women’s experiences of sex. It begins when the bride’s father, Greg, gives a speech at the wedding about the bride’s sexual play with Barbie dolls as a child (every bride’s worst nightmare). And that speech spurs the Woman into telling a story to the bride’s stepsister about two women at a bar, a singer and a bartender. It’s a romance that’s become sexually fraught because the singer is ashamed of the shape of her vulva and is planning to undergo a kind of labiaplasty surgery known as “the Barbie procedure.” Then the Woman shows up and helps the bartender and singer fuck in a playground slide. But in between that frustrated beginning and that cathartic ending, the woman and the bartender tell each other what I think are the novella’s scariest stories. One is about a professor who makes dolls out of little girls’ corpses. And the other is about a father-daughter pair who kidnap and mutilate women together. I was really affected by the mixture of horror and catharsis and liberation throughout the sequence. It was a heady and, as you were saying earlier, confusing thing to encounter as a reader.

I was very tired of the idea that, ‘Oh, a woman is a sexual aggressor because this horrible thing happened to her.’ Is that really our only reason why a woman can be a horny monster?

KW: Some of the pieces of that sequence developed as I experienced and learned about things in the real world. So, for example, while I was writing the book, I was also working separately as a content writer on a contract basis. And I was assigned to help women who were sexual health advocates write a free guide about labiaplasty and its potential harms. So I had to research labiaplasty for many, many, hours, and that’s when I encountered the very real “Barbie procedure.” This is an operation that was developed to make a woman’s vulva look flat and “neat”—“neat” is the word I kept seeing, “tidy,” “clean.” This is a plastic surgery that is solely for the aesthetics of the vulva, even though you lose sensory tissue, and you can also damage the clitoris and clitoral hood. I was not pleased reading about these things. And the book already had some dolls in that scene, and so the Barbie procedure just seemed like an obvious fit.

While I was writing, I also learned about the other stories you mentioned, which are the only other parts of this novella that have some basis in real, true-crime stories—those about the man who made dolls out of the corpses of young girls, and the one about the father and daughter. I think those are the parts of my own narratives I’ve inherited about being a woman in the world. And after I learned about those incidents, I just remember thinking, “Ugh, get out of me, stop being in my head.” So they had to be in the book, I guess, for that reason.

CD: Well, the woman says this really interesting thing of the father-daughter torture team. She says, “They wanted what they wanted and they took it.” Which speaks to the fact that, yes, these people are doing horrific things, but what they’re doing also started as a fantasy, for them. What could be a more literal living out of your own fantasy than making a real human corpse into your fantasy doll?

KW: Yeah, totally. And I also became really interested in the idea that there are always these stories that are trying to break down the psychology of, for example, the man who dug up corpses and made dolls out of them, like, “Oh, he did it because of this. He had this trauma that there’s this reason why he did these things.” And I thought about how a figure like the woman would be pretty uninterested in that reasoning versus the actual act of just grabbing what you want.

CD: Your book doesn’t shy away from depicting sexual trauma, but it also never focuses on trauma as the sole reason that anyone acts in a certain way, sexually or otherwise. It’s a real intervention, given the ubiquity of the term “trauma” in today’s discourse around sex. Was that a conscious choice, on your part, to avoid the language and narrative structures of trauma?

KW: Yeah. As a person, outside my writing, I value conversations around the impacts of sexual trauma. They’re important. But in the world of fiction, in the world of an erotic novel that is moving through pleasure and desire, I was finding myself very weary and tired of the idea that, “Oh, a woman is a sexual aggressor because this horrible thing happened to her.” Is that really our only reason why a woman can be a horny monster? Why can’t she just be the horny monster, you know?

CD: Let’s talk more about her, your central monster-character. Even though the woman’s senses are so finely tuned, and she really takes in the world through her body—is, in some ways, nothing but a body, one that tastes and smells and touches and fucks—she lacks most of the markers of physical character description. We don’t know what color her hair is; we don’t know what her build is. You’ve also labeled her with a prototype instead of a specific name—“the woman.” Why did you choose to make your focalizing character a kind of everywoman in these ways?

You experience the world through your body, but your body is also read by others. Those two things are too interconnected to be separated.

KW: Early on in the writing of this book, one of my graduate thesis advisors, Elisabeth Sheffield, said, “It’s probably intellectually and artistically dishonest to ignore that the woman is passing through this wedding of all these white people so easily that she’s probably white.” And I was like, “Oh, yeah, you can’t write an ‘everywoman.’ That was naive of me.”

And so that is where I became interested in further developing this idea of whiteness throughout the book. You experience the world through your body, but your body is also read by others. Those two things are too interconnected to be separated.

That also brings me back to, what I was talking about with the corset piercing in the mansion, or the erotic shaving scene. These oppressive ideas of what a female body is supposed to look like come from white standards of beauty, specifically. Hairless, thin, all that stuff.

And so the wedding itself just became whiter and whiter as I wrote. It was important to me that it wasn’t divorced of race just because there are only white people there. Whiteness is as racialized as being nonwhite.

CD: This is flagged in the book’s title, of course. “White” is doing a lot of work there.

KW: And it’s not just about the purity fantasy of weddings, which is already disrupted the moment the reader realizes the bride is pregnant. It is also about white, upper-class codes of conduct.

CD: I’m curious about your experience of reading your work in public. Porn is not a shocking thing to encounter in San Francisco (your and my home city) in the year 2022, but the genre definitely still has its associations with taboo in some circles. What’s it like to know that you might be arousing your audience, or even angering or shocking some of them?

KW:: If they’re just angry because it’s porn, that’s not an interesting critique to me, so I don’t worry about it. I’ve mainly gotten feedback from the audience in the vein of, “I was very frightened and aroused.” And I’m like, “Good. Perfect. It worked.”

![‘House of the Dragon’ Recap: Season 1, Episode 8 — [Spoiler] Dies ‘House of the Dragon’ Recap: Season 1, Episode 8 — [Spoiler] Dies](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/house-of-the-dragon-recap-season-1-episode-8-viserys-dies.jpg?w=620)