“The News This Week” by Julia McKenzie Munemo

“Did you hear about Ralph Yarl?” I ask George, my 17-year-old Black son on Tuesday night, five days after a white man in Missouri shot the 16-year-old Black child in the head and chest for knocking on his door; three days after a man in another state shot at a car that’d pulled into his driveway to turn around—20 year olds lost on their way to a party, and no cell service in those woods—killing the woman in the passenger seat; two days after a white student on my husband’s campus called in a shooter threat and my son and I had spent some of Sunday and Monday worrying—not for the life of his dad, whom we knew was unharmed, but for what it might be like to feel safe in this world again; the same day two cheerleaders in Texas were shot for mistakenly opening a car door in the dark, thinking it was their car. What has happened in this country that shooting at strangers has become our answer? What triggers our fears so deeply? Or is it that we’ve always been this scared and now just everyone has a gun?

George nods, keeps his eyes on Football Manager, sighs softly like his father might, sounding older than he is, and at a distance. I think he wishes he believed that if he knocked on the wrong door, sent to collect his younger siblings, this couldn’t happen to him. I think he wishes it were as simple as this world being so sad. He makes that sound, like he’s sighing from far away, and is it my job to bring him closer to this fear, or to let him stay distant?

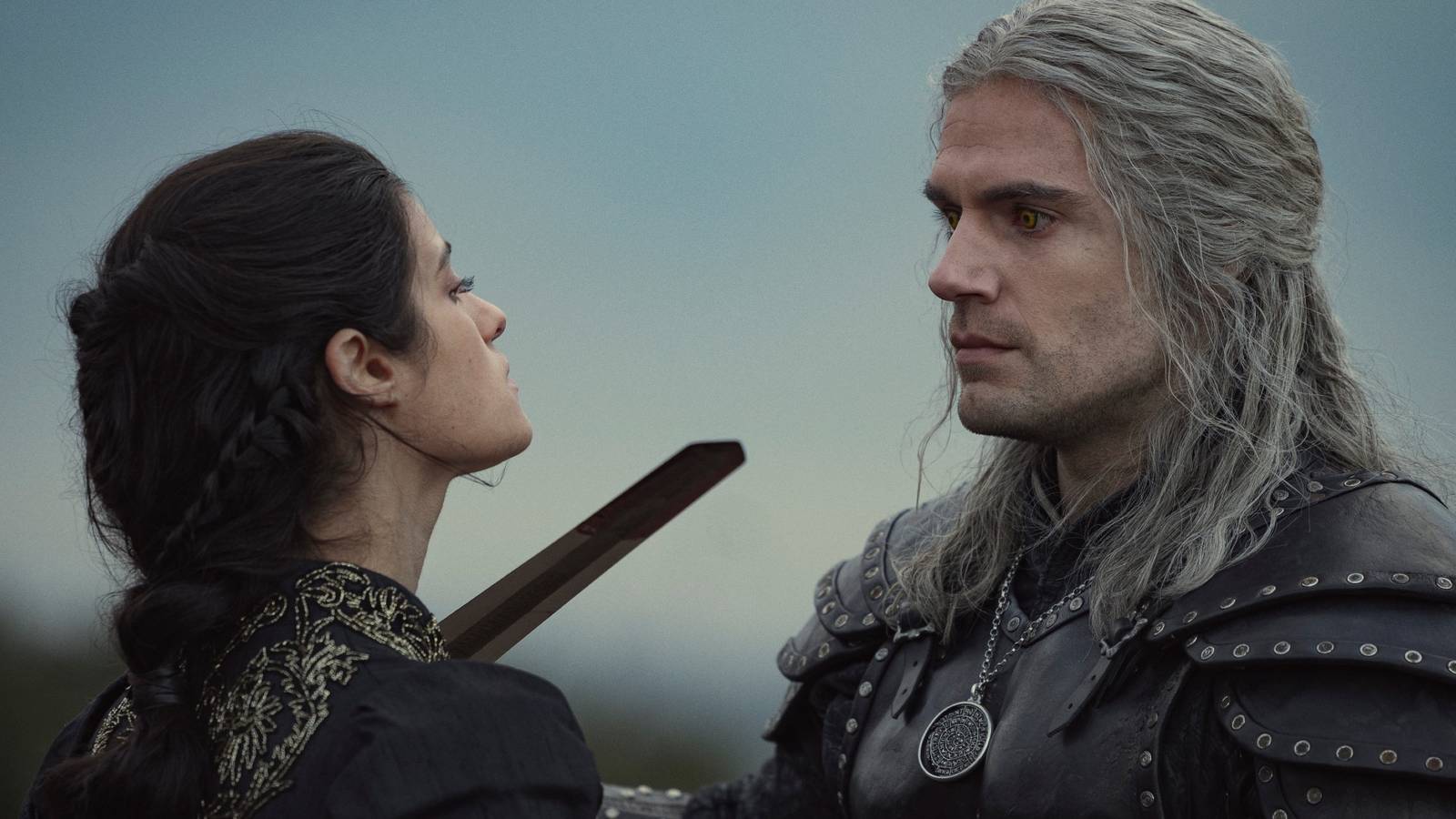

“I tried to start watching a new show with George tonight, but he just played Football Manager on the couch next to me,” I’d texted my husband Ngoni an hour earlier. My second son and I, living alone most of the time these days, have been bonding over TV shows and Martin Scorsese films.

I’m taking this too far, his eyes tell me.

“Sometimes just being in the same room is enough for George,” Ngoni reminded me. Sometimes George and I consume content together so it can be discussed and dissected and understood. Sometimes we just sit on the couch together—parallel play, they called it when we were talking about two year olds. I can still do that. I can always do that.

“Do you remember the night I told you about the shooting at the Sandy Hook school?” I ask next. He’d been just one year older than those children, too.

“Nope,” he says, looking up from Football Manager with annoyance. I’m taking this too far, his eyes tell me. I stop talking and scroll through my phone and realize my second son doesn’t remember an America where the school children weren’t being killed by guns. I stop talking and scroll through my phone and wonder what Ralph Yarl’s brothers thought about when he never arrived to collect them.

“I’m kind of heavy from the news this week,” I text Julius, my first son, in New York on Wednesday after we’ve had an exchange about his day at school and he’s asked how I am.

“Can I call?” he texts. Would the answer ever—ever—be no?

“I can’t imagine an America without racism,” I tell him when I pick up, “but I can imagine one without guns.” I don’t add that my imagination paints a giant magnet in the sky sucking up all our weapons, finite metal objects to be collected and destroyed. “And even still with racism, that would be better.”

“That would be better,” Julius agrees. “But every time something like this happens, I think we’re stretching and stretching and it just means the breaking point is coming sooner.” He’s talking about his favorite topic: when the nation states fail and news media is revealed to be the façade he’s long known it to be, and we rebuild society from the bottom. He really believes this day is coming. It’s his only hope in this world and who am I to say he’s wrong? Do I want him to be wrong?

“It’s not only race,” I tell George on the couch. “A young white woman was killed when the car she was riding in drove into the wrong driveway and the owner of the house came out shooting.” Why do I feel compelled to tell him this? Do I tell him this so he doesn’t feel like he’s the only target?

A detail I keep back: as the bird flies, this one happened around the corner. I want these things to only happen far from us. I want to pretend the Trump signs we drive by on our way to my mother’s house, the mall, the train station aren’t indications that this could happen to us. White mama, Black boy, side by side in a little orange car. If it breaks down? If we get lost and turn around in the wrong driveway? If I have an aneurysm and George runs for help? Knocks on the wrong door?

“I think this is all about covid,” Ngoni will say over FaceTime on Wednesday night. “Two years of lockdown made everyone so much more paranoid.”

As a child I worried my mother had been in a car accident

each time she was late to pick me up.

“I think this is all about guns,” I will say. My phone will be propped on my bedside table while I fold laundry. He will be ironing his shirt for the next day. In this new life of jobs at different colleges, we talk every night on FaceTime, but we sometimes don’t look at each other’s faces. “Fine to be paranoid, but if everyone didn’t have a gun, would Ralph Yarl just have been threatened with a baseball bat, plenty of time to outrun the old man? Would that girl Julius’s age still be alive?”

As a child I worried my mother had been in a car accident each time she was late to pick me up, that she’d drop a cigarette on the floor in her sleep and the house would burn down, that the airplane she was traveling in would fall out of the sky. The children today, their fears. I can’t begin to catalog them, or how much more likely they are to happen.

“Sometimes I think I just want to write my book, that that’s the contribution I should make,” Julius tells me through my AirPods. I want him to think exactly that thing and not any other thing. “But other times I think I have different skills. Maybe I could make a difference, ignite the next phase. But do you know three of the original BLM leaders died under mysterious circumstances?” He talks for a time, sources confusing and maybe exclusive to TikTok—which he would shame me for not trusting—asking: what if he became a leader of the movement and was killed by the CIA?

“It won’t be the CIA,” Ngoni will tell me over FaceTime in a few hours. I won’t ask who it will be. “But I’m glad he’s asking these questions. It means he’s not among the apathetic of his generation.” I can’t hear you I can’t hear you I can’t hear you. Just let my sons live their lives in peace, let them find joy and meaning, and later, so so much later, let them die of old age. This is my only wish.

I won’t move for fear of breaking the connection.

“Do you ever feel scared driving around in this town?” I ask George just one more question on the couch. I know he’s tiring of this, of me. But then I feel something else beyond his silent shaking head. A sweaty foot still in its sock pressing against the crook of my elbow. Casually. Like maybe my elbow is in the way but he’s not worried, we can share this space. Sometimes it’s enough to just be in the same room. Now I won’t move for fear of breaking the connection. I sit slightly sideways also, so casual and maybe not on purpose, but my body maintains the pressure against his body, so his body knows that his mother is here on the couch next to him, always. I scroll through my phone like I care what it says.

Would he tell me if he were afraid?

I am so scared I will lose my sons to this world.

“Before Sertraline, I used to think about all this stuff so much more,” Julius tells me through AirPods, “and I feel guilty about that. Like the medicine is just the same propaganda as everything else, a happy pill we take to keep us quiet.”

Ngoni will tell me over FaceTime in a few hours that propaganda isn’t the word he means and I’ll mutter something about our son being 20 and thinking it is the word he means and that isn’t the point, really. The point is that Julius might be considering going off his antidepressants because he thinks that might help him save the world, and these concentric circles frighten me on different levels I don’t have the words to express. They have something to do with me never wanting my sons to carry a gun and how the revolution he’s discussing won’t be peaceful; they have something to do with me worrying that grandiose thinking is a thing my first son has in common with my father, and does that mean it’s a sign of schizophrenia?

“I need to do the dishes,” I say after George’s sweaty foot slides away and he readjusts himself to sit with the laptop on his lap and Football Manager (his team is winning!) running his emotions. But I come right back into the living room because I suddenly very badly need to apologize for scaring him so late at night (it’s 8:20) and bringing him into this broken land in the first place and asking him to try to survive here when the world he experiences is a world I will never experience or understand and who was I to think our children would inherit a better one? But he’s not in the living room anymore, he’s downstairs now, standing outside the basement door, thinking—maybe—that I don’t know what he does out there. Or thinking—more likely—that I do. That I get it. Smoke wafts up my windows.

I spend so much time fighting the anxiety,

sometimes I forget that its job is to cover the fear.

“Let’s look at this structurally,” my therapist will say over Zoom on Friday morning, and I’ll wonder what she could mean. “All three of your men are in danger in this country, and your sons are both exhibiting signs of fear. Julius, for lack of a better word, through paranoia—” and I’ll wince. I will know she does not mean paranoia and I will know that she does. And I know that just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not after you, and I know that paranoia is the first word in one of my father’s diagnoses and I know that in addition to being afraid, so very afraid, that I will lose my children to this country, I am also afraid I will lose them to my father’s disease. But I breathe and I listen. “And George by numbing out.” And this I can hear.

I spend so much time fighting the anxiety, sometimes I forget that its job is to cover the fear. I forget how to tease it apart from the fear and sit with these things separately. “Anxiety is a constant, obnoxious force,” my therapist will say, and I’ll think about a child from grammar school, always buzzing in my ear when I was trying to learn science. “But fear, like grief, will come and go, and the trick is to learn to sit with it, and to breathe.”

I’ll recognize that it does come and go, the fear, and I’ll think about how I learned to put my fears in a box as a child. (Brick houses don’t burn down, stop worrying. But then the brick house across the street burned down.) And that fear closed away opens the door to anxiety.

“I am feeling some of the awfulness of the world after this week in the news,” I text my mother when she asks me how I am on Thursday morning.

“The news this week is awful,” she responds. “I am only happy the stupid old man didn’t manage to kill Ralph Yarl.”

“Me too, that kid is a wonder,” I type across state lines to my mother, not asking if she knows he ran away after being shot twice, that he knocked on three doors before someone helped him. Not asking if she knows what his brothers were thinking when he never came to collect them. “The girl in Hebron, NY, tho. The cheerleaders in TX. When did we become such paranoid people? Ngoni says covid. I say: when they gave every American a gun.”

“Or when we decided it was okay to own other people,” my mom types back faster than is typical for her poor eyesight and arthritic thumbs. “Always knowing deep down it was wrong and indefensible.”

And then she adds in a text bubble all its own: “Hence guns.”

My mother. How many 83-year-old white women in this country would throw down slavery as the cause of it all in one simple text, making her daughter feel so much less alone?

I asked if he’s scared to live in that world.

I am so scared to live in that world.

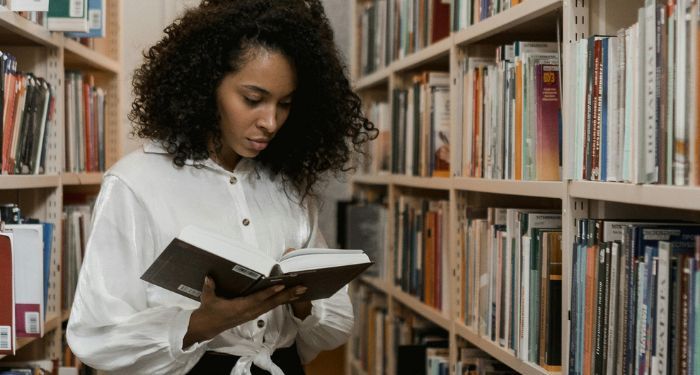

“Up to pee and this thought occurs to me,” I will type to Julius—who I know leaves his phone on silent—at 3:23 am on Thursday, on what will become my first sleepless night in a long time. “You might have thought about all this stuff more pre Sertraline, but you weren’t able to do anything about it bc of being too depressed to act/move/do. What if Sertraline allows you just enough freedom from that to be the very thing that gives you the ability to do something about it all?”

At 9:04, before he’ll even have seen the first text, I’ll be just out of the shower and will text him a Spotify link to Mos Def’s “UMI Says,” and hope he gets the message. It’s a song I sent George some months ago, too, after a similar conversation justifying antidepressants. Who can shine their light on this world without them?

One fall night last year, George and I drove through the backwoods of Massachusetts on our way home from a soccer game, and he spoke about beauty in nature and the end of the world.

“I know I’ll live to see a world without trees,” he said, looking at the trees all around. I strained not to see them, to imagine not being able to see them. “I need to paint all this before it’s too late, so we can remember.”

I’d recently hung one of his paintings on the wall, a landscape based on the view of trees and grass and sky from our back stoop, but all purples and reds and dark blues. That it is recognizable as our backyard speaks to his talent. That it represents how he sees this world speaks to his mind.

“I’ve been thinking about life after society has crumbled,” he said, and I asked if he’s scared to live in that world. I am so scared to live in that world.

“No,” he said quietly. Confidently.

“Because you feel equipped for it?”

“Humans adapt,” he said. “We always have.”

We were quiet for a moment, though I was certain it was my job to say something next. Instead, he continued: “I’ve been thinking about what it’s my responsibility to fix, since I was born into this moment.”

Overwhelmed with all there is to fix, I sighed and put my hand on the back of his neck, thankful he was born into this moment. That he’ll find what to fix in it.

Tonight George will have his friends over for homemade pizza—he and Ngoni built a wood-burning oven during the first covid summer, and he dried it out for the season last night; inaugural pizzas for him and his girl. He’ll blend his homemade tomato sauce, mix the dough in my KitchenAid, shred the cheese all over the counter. His friends in this small New England town are all white and they won’t talk much about Ralph Yarl. They’ll giggle and share stories about college visits they made during April break and smoke some weed and eat some pizza. And Ngoni will come home while they’re out there, pulling into the driveway like he does every second Friday night, like it’s home. I’ll pull the casserole out of the oven and wipe my hands on my apron and put on lipstick when I hear his car (just kidding; I’ll be wearing sweatpants and flip flops and dinner will be takeout; he’ll be tired and grouchy from a long day and a long drive and barely kiss me hello) and I’ll watch him walk up the stairs with his suitcase, like he’s checking into a hotel. Tomorrow, George will go to work at the restaurant where he’ll impress the rest of the staff with his maturity and cooking skills as he does every Saturday, and Ngoni and I will take down the corn house he built a few years ago to keep the squirrels out, which collapsed under two feet of March snow. The sun will shine, or it’ll be cloudy. The dog will chase the ball I throw for him. Or he’ll lie in the grass and watch for deer. George will come home from work smelling like bacon. Or—.

We’ll breathe.