Since Walt Whitman, the American sentence has shape-shifted in and out of forms, from race-car lyrical lines that drive off the page, to fields of hailstorm words floating in white space in a way that resembles visual art, and back to semi-formal stanzas that lilt and groove around a pentameter-like beat.

I’ve designed my poetry collection Tiny Extravaganzas around experiments that push against the boundaries of the American sentence. There’s a quiet thrill in being part of a tradition that turns away from the English iambic pentameter line and tries to define the characteristics of a sentence that is uniquely American. We’re at a time when the sentence has virtually no limits. I can build an entire stanza around one transitive verb, so the verb is fixed and the stanza is free. I can use pauses to force the breath to shorten over three monosyllable words, and then speed up or get talkative to create the drama of conversation—and interrupt or end it abruptly after the first word following a line break, just when you feel the line is getting started. There’s a way to gently push white space around words, stretch a melody out. Manipulating pacing across syntax, and hearing the tiny explosions that result, is a puzzle and a thrill.

My sentences focus on identity, dialect, and cadence—often indirectly, but in a radically democratizing vernacular that pulls toward and away from the lyric. I’m interested in chasing rhythm and chopping it up, and generally finding new ways to shatter the traditional American sentence with style and verse. I veer from talkative to incantatory, with tone shifts from jazz to lament. I work on a presumption that the sentence is political and a woman must move the sentence in new directions.

Here are collections by women working the American sentence relentlessly, applying power through acoustics and rhythm while documenting harsh histories. Some poems are elliptical or visually fragmented, and others seem orderly on the page but the sentences are boiling inside. Some pretend to be prose, but they are not. Like me, all of these poets are working in a style that is closer to music and chant than to conversation.

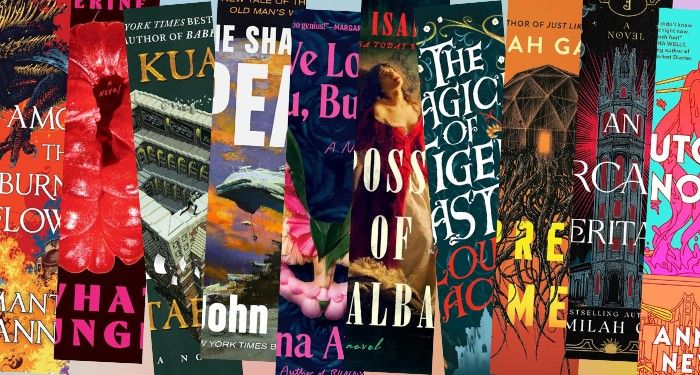

Arrow by Sumita Chakraborty

Chakraborty language is so cosmological and expressive that you can’t help but wonder if her larger project is to about language fails to express. “Some bright and sun-kissed, some dark and pulp-dashed, / your and our blood across the burnt orange schist,” she oozes. Her tone is effusive, her diction lush. But below her sweepingly lyrical lines and her conversational intimacy is linguistic play and argument. The heart of Chakraborty’s collection, and a showcase for her radiant talent, is her eleven-page poem lament for her sister, “Dear, Beloved,” and possibly the most poignant and skillful short epic in contemporary poetry. Her book exists in the liminal space of grief, but it is grief that gives shape to the book. Her high emotional pitch is bracketed by poems in conversation with other writers—grief does not sideline her intellectually, and she is determined to make something of it. O Spirit extracts and remixes words from Melville’s Moby-Dick; another poem refracts Rilke’s Les Fenêtres. Her riffs create a feeling of improvisation but she is the middle of an intellectual conversation. Language outside of time is the argument she hinges the book on. Chakraborty makes her case through Michel Foucault: “The original title of The Order of Things is Les mots et les choses, or Words and Things. The substitution of Order for Words speaks to one of our most pervasive myths, that words have a clear order.” As she weaves a myth of her sister into an epic dirge that includes a Greek creation myth, Chakraborty is telling us that language is meaningful, even if time is disorderly. She is working out what pain is. “Please leave the window unlatched,” she says.

West: A Translation by Paisley Rekdal

Rekdal’s project is a hybrid multivocal poem documenting two histories: the transcontinental railroad and Chinese migrants detained at the Angel Island Immigration Station during the Chinese Exclusion Act. The book is part oral history, part “translation” in which she turns the American sentence into a document of witness. The poems often locomote down the page, without stanzas, as in Soil: “General, / we worked your grading to Monument Point, in thousands / drilled and blasted, rent the very foundations / of the earth until these hills swarmed with our fresh / encampments.” She takes different approaches to educate us. One poem is a list of questions to show us what it feels like to be Chinese and suspected: “How many water buffalo / does your uncle own? Do you love him?” She is graceful about filtering the voices of migrants through her own. In Lament, on the invention that is the train, she recreates the American sentence: “the buckskin ties tamped tight / to their irons, / shadowing his canvas margin.” The snap and lyricism is her precision style; she inclines to lyricism naturally but defers to journalism for this book. She works in dialogue, correspondence, photographs, illustrations of torn maps or torn notes, and miniature essays or elegies. The prose sections reveal how the railroad enabled industrial expansion, political rallies, the transfer of munitions, and human settlement. At every step, she complicates the narrative by connecting immigrant stories to ways the railroad creates conditions of power or powerlessness. In Close Eye: “Between 1854 and 1929, over 250,000 children were sent by train from New York City to the West to be adopted.” After children arrived in the “orphan trains” were they protected or harmed? “Perhaps, like me, you are afraid to find out,” she says.

Grief Sequence by Prageeta Sharma

Every variety of mood appears into Sharma’s sentences, which are sometimes so interior that they are uniquely beyond the American line and sentence—yet still materially in it. Sharma’s sequence combines lament, letter, diary, conversation, and obituary. It is heart-shatteringly good and accessible. Sharma expands the tradition of lament in verse, as original an experiment in understanding and processing grief as anyone has written. The sequence mimics the cycles of grief itself, an intimate meta-journey into the riddle of sorting out what time is when your lover no longer exists. As she writes, and writes, trying to find the life in her, and the life of an expression in the form of a sentence, you cannot help but wonder what a sentence is, if not an act of duration. And when the sentence is over, what memory stays? Sharma brilliantly creates memory through her sentence, shattering any grief-cycle that has come before. She has created, artlessly, a theory of sentences. The senses blur and combine in Sequence 1: “Memories curved and then sounded: were sibilant and jest, and from not-his-mouth, and not-his-teeth, and the breath grew so sharp and he grew so thin and gaunt that he was buried in a slander his body made of him.” Because many of the poems are presented as lists or prose poems, within the framework of a chronology of dying and death, you can easily fooled that Sharma is writing prose sentences rather than verse—but she takes care with her sentences and is fiercely intellectual. She shines when she loses the encumberments of line breaks, which seem, in her deft hands, altogether unnecessary to the American sentence.

The Beloved Community by Patricia Spears Jones

Spears Jones’ imagistic internationalist, docu-political sentences resemble conversation but stop you in your tracks. Her opener in Celia Cruz Snow Angels electrifies: “The Great Gatsby jazzed the sorrows of summers where the wealthy misspend their wealth.” In one sentence she sums up the tone and sweep of the novel, soused partiers, and the way they “misspend” their sad, rich, empty lives. She is deeply invested in the ability of American speech, both conversation and slang, to reveal the consequences of materialism: inequity, poverty, murder, violence, masculinity. In Poverty, she marries her diction and sentences to the spareness of the condition itself: “[Poverty] Is a broken tooth / No smile— // Is bone poorly reset / Weak limbs, medicos various.” The tooth remains broken, the shoddy medical care creates lifelong problems. She is expert at shaping the way a sentence sounds around its content, especially when pain of family secrets and histories come into play. In Cousins, the stanzas shorten from seven lines to four, as if narrowing in on a secret. From the first line (“What genes we carry this making of Americans”) to the last (“cousins many times removed”) is about discovering, or hiding, an uncomfortable ancestral truth. Chillingly, she demands to know: “Who grabbed the girl and made her pregnant? / Who walked away when her father was lynched? Who snatched / whose land?” And when Spears’ diction is easy, you know something else is coming. Adornment begins: “Red cap / Red scarf / Red balloon // phalanx of protesters / quarrel of militia—off camera.”

Blood Snow by dg nanouk okpik

What syntactical tension electrifies Okpik’s poems! The poetic throughline is the metaphor of flight. Her sentences mimic it by moving forward while monosyllables pile up and slow you down, pull your attention back to earth, to a single syllable. It forces you to look, recite, listen. Her sentences are dense while the book has an emotional spaciousness about it. Some of this is pure technique: multiple beats on a line. Her pile-up of heavy beats and strong diction recalls Gerard Manley Hopkins’ amplified speech, measured by duration in what he called “sprung rhythm.” She is as close as anyone has come to approximating that technique with contemporary elan. Lovely and rare is the way her diction takes a multitude of sounds from the natural world, evidenced by the way a sentences forces your mouth to twist and your tongue to move around your mouth to get the sounds right: “pistils of bear grass, stamen of indian paints, / ovules of Mozart’s string quartet” in I want to believe. Birds and other winged creatures string the collection together expertly. Mosquitoes, hornets, geese, a woodpecker, bluejay, hawk, duck, raven, ptarmigan, magpie, flea, and grouse have cameos. Where there are no winged animals, there is wind and storm in motion. Over the sentences are an aerial view of imagistic land formations, and contemplations on the inheritance of land. And, as in any aerial view, sentences unwind in long expanses in one poem and abbreviate in short, abstracted views in another.

Oceanic by Aimee Nezhukumatathil

One thing to know about Nezhukumatathil’s poems, even when they resemble fragments on a visual plane, is that she is always writing clear sentences whose meanings turn back on themselves or which slowly reveal more of the narrative. The craft of storytelling with an unreliable narrator shows up continually. The way she turns her sentences turn into poetry is through the breath. It’s a lyrical device to breathlessly roll along your sentences, and it becomes a poem when the breath enters—in her case often breathlessly—and adds emotional color or reshapes how you hear and where you pause. Part of her technique is a jazzy stream of consciousness populated with words that jam up in your mouth: tar, asphalt, fistful, thistle. Her sentence jolt because they are simultaneously propulsive and balanced, a feat because to balance a line is to risk making it flat—but the diction engineers something unusual. In When Lucille Bogan Sings “Shave ‘Em Dry” she upshifts over a line break, and charges forward on the verb: “When I say flower I mean how her song // blooms in the electric Mississippi light.” And Nezhukumatathil has a flair for thickening sentences with meaty sounds such as “shushing tassels” and inserting consonant-connected phrases (“crystals of chalcopyrite”) in a poem packed with easygoing monosyllables. The Whitmanesque title poem Invitation should be read on repeat, for the sounds, but also as a lesson in how to intensify a sentence and refuse to let up: “Clouds of plankton hurricaning in open whale mouths will send you east and chewy urchins will slide you west.”

suddenly we by Evie Shockley

Shockley’s homophones and verbal play shred the sentence into its most basic units. The result is as charming and fun as it is political. Her book probes inheritance: what we inherit from history and from language. She undermines the value of language itself with slick technique. Her poem v is a pun in a square: starsarewh / atshinesinthe / spacesmadeb / etweenuswhe / nwegetcloser. How experimental she pretends to be! She wants us to look closer, read slow, insert spaces between words. The larger project of this tiny poem is getting closer figuratively; by the time this poem concludes, we understand Shockley better. She is an elaborately smart lyric poet. Her sounds are expert, and with lowercase letters and experiments as a distraction, she adores styling a proper line: “my pose proposes anticipation. i poise / in copper-colored tension, intent.” It’s a winning approach. When she writes about segregation, her sentences expand as a way of say that American can limit your body but not your mind. She plays with opposites and form in carolina, a beautiful poem with alternating quatrains and tercets: “I’m dark except where I’m / darker,” followed by a memory catalogue to show us how resilience works. It is a rare collection in which poetic forms vary this much from one page to the next. No sentence in this language, Shockley indicates, will ever be enough. Lines are captive in stanzas, spliced open, indented. She is not afraid to use and reuse words every which way: “the jitterbug got the jitters,” she says in Rose.