Electric Literature Urgently Needs Your Help

For the 15,000 people who visit our site every day, reading Electric Literature costs nothing. And yet Electric Lit is not free. We need to raise $25,000 by December 31, 2024 to keep Electric Literature going into next year. If the continued existence of Electric Literature means something to you, please make a contribution today.

When I was a ‘90s teen consuming literary novels and stories at a breakneck pace, I couldn’t have imagined that three decades later, there would be a glorious abundance of interesting fiction written by and about the Indian diaspora.

It’s perhaps because of today’s range of culturally grounded books that in my second short story collection, How We Know Our Time Travelers, I felt free not to make culture an element of narrative interest. As in my first collection, which often delved into dramas around identity—race, caste, and gender—the protagonists of the new book are Tamil Americans with both Christian and Hindu backgrounds. The far greater cultural force exerted in the book, is that of the West Coast, with its social and environmental particularities.

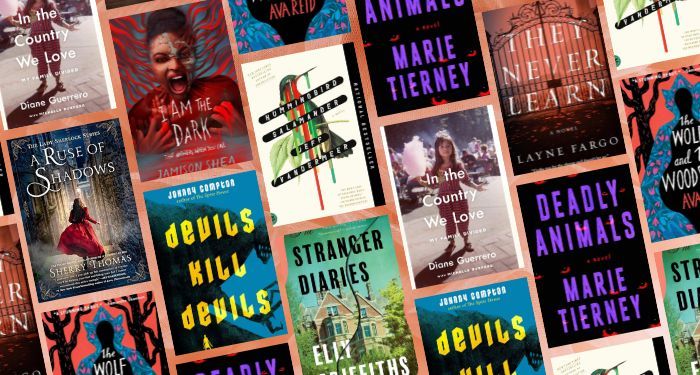

For the last few years, I’ve been secretly gathering my list of diasporic authors I’d like to invite to a massive dosa fusion dinner party with bird’s eye chili drinks. I don’t know, really, if they’d all get along, but hey, a little friction could be a fun thing (and makes it more likely we’d all want to write about it)! The following books strike me for their imagination, observations, and inventive spirit—and often, their moving risks. Whoever says it’s all been done clearly hasn’t encountered these works.

Loot by Tania James

James is one of the best contemporary literary fiction authors in the Indian diaspora—every book she publishes is an event for me. In her latest, a fun historical novel and love story set across 65 years in eighteenth century India and Europe, she tells the story of a teenage woodcarver who is asked to build a tiger automaton for a sultan’s sons who’d been captured and returned by the British. It is to be “a gift of such grandeur and ferocity that it will silence all memory of the boys’ exile.” When the British attack and plunder Mysore, they seize the automaton and place it with other plundered art in a collection, the woodworker must go get it back.

This is Salvaged by Vauhini Vara

One of the things that intrigues me most about Vauhini Vara’s stunning fiction is how intimately embodied it is, how unafraid it is of revealing all that is flawed or potentially unappealing about human bodies. This collection of ten visceral, intelligent stories are tied together by questions of connection, family relationships, alienation, and grief in all its different permutations. Where Vara’s The Immortal King Rao contended primarily with algorithm-driven technology, which sometimes uses quantification and rules to predict, This is Salvaged pays more attention to characters’ potential for unpredictable and emotionally demanding action.

I’m a Fan by Sheena Patel

Sheena Patel’s voice-driven debut—what a thrill. In what feels like a diary, a self-destructive young woman (who has a boyfriend) breathlessly reveals her sexual relationship with a toxic married white man and her obsession with one of his several other girlfriends. That girlfriend is an Instagram lifestyle influencer, and her careful social media curation involves expensive, tasteful things. The book involves not only an engaging, up-to-the-minute story but also an acidic critique of overconsumption, class, structural racism and patriarchy as filtered through online spaces.

Circa by Devi Laskar

In this lyrical coming of age novel, which follows Laskar’s acclaimed The Atlas of Reds and Blues, a young Indian American teenager feels caught between the traditional Bengali culture inside her house and the culture of the American South outside its doors. She and her friends, a brother and sister, rebel in all kinds of ways, much to her parents’ disapproval. When a tragedy occurs on the cusp of adulthood, grief soaks into everything, altering the choices they make and the people they might otherwise have become. Told in second person, the narrative follows the evolution of the friends’ relationship.

A Small Sacrifice for an Enormous Happiness by Jai Chakrabarti

Jai Chakrabarti is a master of the realistic short story—I’ve been keeping an eye on his work ever since he was the 2015 A Public Space Emerging Writer Fellow. In these stories, he unfurls the vagaries of the human heart. A gay man confronts his lover’s wife with his longing to have a child. A woman wonders if her husband sees her as anything more than a caregiver. A married music teacher is attracted to a student in India. Brothers take an overnight bus to go become monks—one of them has abandoned his wife and child. And the beauty of Chakrabarti’s introspective sentences! Here’s one: “She was grateful for it now, that sublime feeling of one’s own silence.”

A New Race of Men From Heaven by Chaitali Sen

Sen is a versatile fiction writer who excels at conveying small but devastating moments in her characters’ lives. In this, her first collection of stories, which won the Mary McCarthy Prize in Short Fiction as judged by Danielle Evans, she writes of a baffled author who is lauded for a story he didn’t write, a couple whose different responses to a parent-teacher conference for their twins leads them to realize their deeper differences, a couple anxious that their neighbors are Trump supporters, and a young woman who discovers her mother was responsible for breaking up her father’s earlier marriage.

Mirror Made of Rain by Naheed Phiroze Patel

The narrator of Patel’s debut, which explores the clash of conservative tradition and modernity, is a young, upper middle class Parsi woman with a difficult relationship with her mother, who has mental health problems, and struggles around addiction and rape. The novel looks at trauma as an inheritance. Drawing an angry, self-destructive female narrator is a particularly fearless, taboo-breaking move for a diasporic author. The dark vigilance of an affluent, patriarchal Indian community—its exertion of control over young women by fomenting fear around their reputations, valuing that above all else—is finely drawn.

How to Make Your Mother Cry by Sejal Shah

Reminiscent of Maxine Hong Kingston or Claudia Rankine’s hybrid work, Sejal Shah’s collection of 11 evocative linked stories is lovely and unusual—experimental without being showy. First-person stories about diasporic girlhood, young womanhood, and finding one’s way that frequently feel autobiographical are interspersed with images, ephemera, and letters. What is especially attention-getting here is the unusual poetic and impressionistic language. In one story that leaves a mark, “mary, staring at me” a girl massages cured sesame oil into the back of the narrator, whose “back twists into the treble clef.” This bold collection follows Shah’s more straightforward This Is One Way to Dance: Essays about Race, Place, and Belonging, and certain elements cross both.

The Way You Make Me Feel: Love in Black and Brown by Nina Sharma

This thoughtful memoir moves us through Sharma’s relationship with her husband Quincy, a Black man, and her parents’ anti-Blackness, which seems to soften as they get to know Quincy. Interleaved with relatable scenes of family life are relevant slices of Asian American history, summaries of caste’s import, and political discussion. Here, too, are glimpses into Sharma’s mental health struggles. Her courageous discussion around race, caste, and more quietly, mental illness, is astute and admirably frank—within many Indian American immigrant homes, these are taboo topics that everyone is expected to avoid.

The Lucky Ones by Zara Chowdhary

In 2002, when Chowdhary was 16 years old, living with her Muslim family in Ahmedabad, a city with a long history of religious violence, a train fire resulted in 58 deaths. The chief minister of the state at that time was Narendra Modi—India’s present-day prime minister, who has taken the country to nationalist intolerance, autocracy, and violent attacks on minorities such as Muslims. He cast the train fire as an Islamic terrorist act, triggering widespread violence. For three months, Hindu mobs turned against Muslim citizens, once friends and neighbors—looting, raping, and burning them alive. Chowdhary’s family, who are memorably sketched this memoir-cum-history stayed inside their apartment to stay alive.

Quarterlife by Devika Rege

This is an absorbing and fascinatingly constructed debut. Wall Street consultant Naren comes home to Mumbai after Prime Minister Modi and his intolerant nationalist party take power and attempt to unmake what was a secular nation and we follow Naren, his brother Rohit, and Amanda, a white woman who has made it her mission to help Muslims in a slum. Most of the book occurs through fascinating, extended jostling blocks of opinionated, philosophical dialogue and debate about conditions in India including income inequality, caste, secularism, and the perceived need for unification of identity in an extremely heterogeneous country.

Twilight Prisoners: The Rise of the Hindu Right and the Fall of India by Siddhartha Deb

This is the swift nonfiction book anyone who is interested in what’s happened to the India of their memories or imagination needs to read. Deb makes a smart, lucid, and pointed case for how the country descended into authoritarianism and religious fundamentalism after Modi and the BJP took control. Deb talks to minority people, jailed dissenters, the impoverished, scholars, and other writers—readers would do well to remember he’s well-positioned to report on and write about this partly because he’s not broadly under threat from censors. Earlier this year, Modi and the BJP unexpectedly lost seats across the country, but this book remains crucial to understanding conditions there, which also have something to say to America.

A Bomb Placed Close to the Heart by Nishant Batsha (forthcoming, July 2025)

Next summer, Batsha, author of Mother Ocean, Father Nation, returns with his second novel, set at the start of World War I—it’s one of my most anticipated. A Bengali revolutionary seeking material support to overthrow British rule and an idealistic graduate student, the daughter of an engineer working around the mines of the West, meet at Stanford, and find themselves of like minds about ideas regarded as radical. They cultivate a passionate romance amidst the heady protests of anticolonials and gatherings of anti-British activists, and intellectuals in Palo Alto and Berkeley. As the United States is pulled into the war, the climate becomes hostile to dissent, and the couple quickly marry and flee to an uncertain future in New York City, where the marriage is tested by their differing ambitions. Look out for this one!