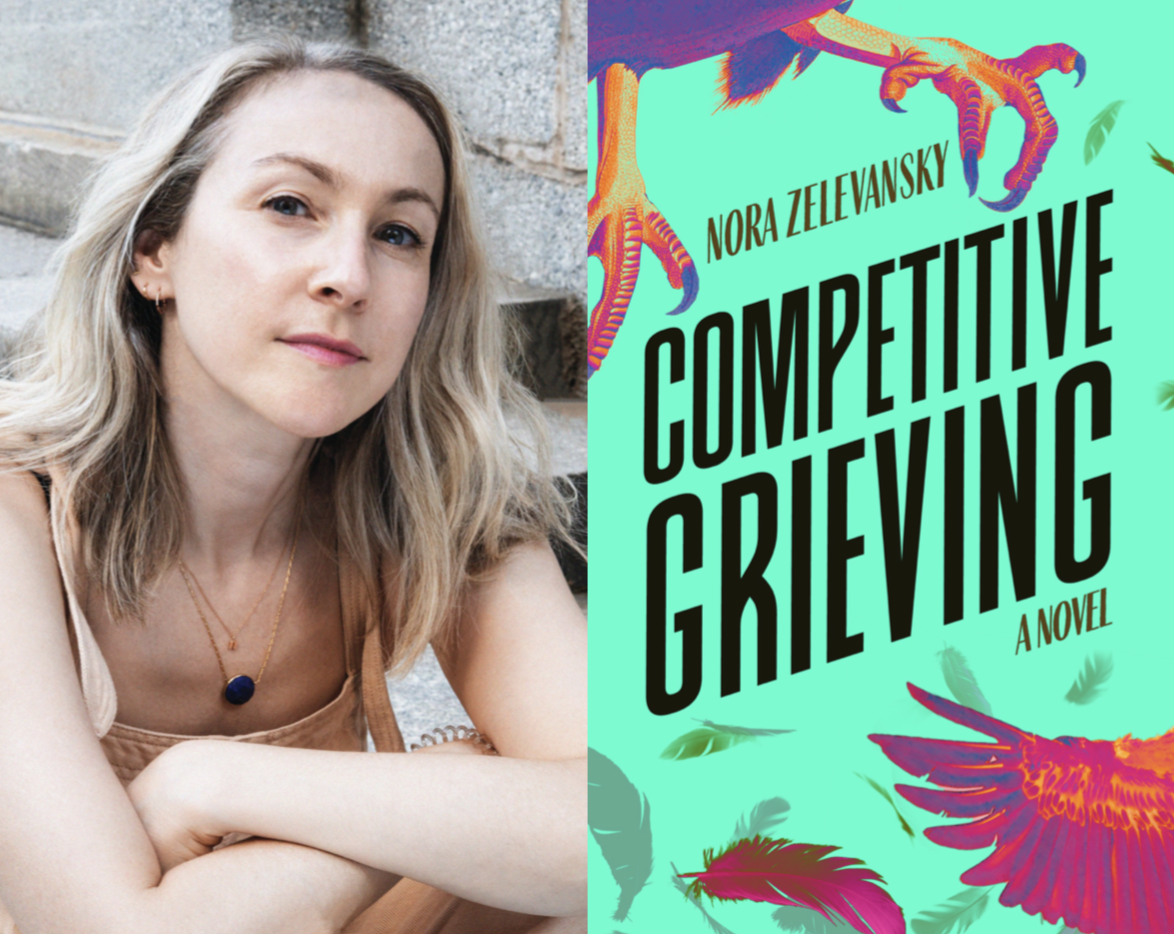

Nora Zelevansky’s latest novel, Competitive Grieving, out in paperback from Blackstone on TK, follows Wren, who is reeling after the sudden death of her best friend Stewart. Daunted by the intensity of her grief, she does whatever she can to avoid facing reality—namely, dreaming up the perfect funeral plans for everyone she meets. But when she is tasked with taking care of Stewart’s estate, she can no longer hide from her loss as she reflects on—and discovers new things about—Stewart’s life.

Zelevansky is also the author of the novels Will You Won’t You Want Me? and Semi-Charmed Life. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, Vanity Fair, Elle, and elsewhere. We caught up with her to talk about parenthood, self-help, artmaking, and the personal story behind Competitive Grieving.

Zelevansky is also the author of the novels Will You Won’t You Want Me? and Semi-Charmed Life. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, Vanity Fair, Elle, and elsewhere. We caught up with her to talk about parenthood, self-help, artmaking, and the personal story behind Competitive Grieving.

The Millions: The impetus for writing Competitive Grieving was very personal for you. Can you talk a bit about that?

Nora Zelevansky: In 2017, a year that was tumultuous for many of us, one of my best friends from childhood died, a friend who I considered like a kindred soul. (That’s not usually how I express myself, but, in this case, it felt true.) He was charismatic and gifted at everything and had experienced a moment of notoriety as a musician, so many people felt close to him. In the aftermath of losing him, I watched (and, okay, sometimes participated) as people behaved not at their best, clawing for a kind of recognition of their significance to him. Of course, the only person who could really confirm or deny any of it was him—and he was gone. I became fascinated by the whole phenomenon and, one day, announced to another mutual best friend that I was going to write a book called, Competitive Grieving. For maybe two minutes, I was kidding. And then I realized I wasn’t.

TM: The novel’s protagonist, Wren, feels so fully fleshed out. Did you find you were infusing any parts of yourself into her character as you wrote her? Did she come to you fully formed or did you discover her as you wrote?

NZ: Thank you! I guess, as a writer, you always infuse some elements of your own worldview into your characters, unless they’re so drastically different from you that you’re envisioning your opposite. I tend to give them exaggerated versions of my flaws (at least, I hope they’re exaggerated). Wren’s habit of planning strangers’ funerals does mirror a habit I have of imagining strangers’ love stories and my own funeral, actually, but I don’t struggle with the same issues as she does in relationships. Maybe, in some ways, all of my characters are Sliding Doors versions of me. I never write with an outline though, so she definitely wasn’t fully fleshed out at the outset and came to fruition as I went along—and was even more fleshed out after my many, many edits.

TM: Though its subject matter is serious, and it certainly strikes darker chords throughout, Competitive Grieving is at its core a comedy, as well as a love story. How were you able to balance the novel’s shifting moods and genres, tackling grave issues while maintaining a sense of levity?

NZ: For me, humor is a gigantic coping mechanism. The most important one, maybe. Especially in dark times (the last few years in the world, for example), I need those moments of levity to keep me afloat. And I like to read that way too, especially lately. I need bursts of light to balance out the dark, an edge of hope to keep me going. So, it was natural for me to approach the idea of grieving with comedy. I find those moments—when you’re reminiscing with friends about someone you lost, for example, and all burst out laughing about some flaw that he had—to be the most authentic and cathartic. Laughter is the truth.

TM: In addition to being a moving story, Competitive Grieving contains a lot of insights that readers can apply to their own lives as they grief. How do you feel fiction might be able to help us lead better lives in a way that is unique from, say, self-help literature?

NZ: I’m not a reader of self-help, though I’ve spent many years covering wellness and editing wellness content. I think it’s totally possible to find solutions via those types of books, but nothing is one-size-fits-all. Sometimes, assuming that there’s one surefire solution can put pressure on us to fix ourselves and make us feel like we’ve failed if it doesn’t help. Stories, on the other hand, contain multitudes. Whether fiction or memoir, to be able to read about someone else’s experience and perhaps relate or commiserate is invaluable. To be able to laugh and cry at someone else’s journey, with someone else, when perhaps you’re working through your own personal issues, is cathartic. Of course, fiction has the added benefit of wish fulfillment, if the author so chooses. In grieving through make-believe, everything can wind up okay in the end.

TM: Since the start of the pandemic, the experience of grief has become ubiquitous, whether people are mourning the loss of loved ones or mourning the loss of milestones or mourning the life they thought they might have. Although you wrote the book before the pandemic, this is the world that Competitive Grieving was published into in 2021. How did you find that shaped readers’ reception to the book? Were you at all surprised by the newfound resonance it took on given how the world had changed?

NZ: Were it not for the 2020 election, which created a kind of publishing blackout except in specific sectors, Competitive Grieving would have been published that fall. I’ll be honest: I was initially bummed about having to wait so long to see it all come to fruition. But it turned out to be the most amazing blessing. The book came out when the world actually needed these kinds of stories, and it became a small part of what I see as an incredibly important conversation about grief. One silver lining to the pandemic’s horrible toll has been a new kind of openness about loss, a dispensing with taboo, and I am so honored to be part of that discussion on any level. One of the greatest rewards of this book has been having people reach out to me to share their own competitive grieving stories. It’s something I never anticipated and has meant a ton to me.

TM: Last year, you wrote an essay about the challenges of grieving while being a parent. In it, you talk about how you found sharing stories about loved ones with your children as a way to communicate your grief. Sharing stories is, of course, what writers do. Did becoming a parent at all change you as a writer or impact your writing? Did it shape Competitive Grieving at all?

NZ: Becoming a parent definitely changed my writing routine, I’ll say that. I used to think I needed some kind of immaculate setting in which to write—only first thing in the morning, only with the right cup of tea, only before anyone spoke to me, only when the moon was in Sagittarius and waning (just kidding—I don’t even know if that’s a thing). But, when that became an impossibility, I changed my tune. Necessity is indeed the mother of invention (no pun intended). Before I had children, I remember stressing aloud to my father, who is a visual artist, about having time to write once I became a mother. He said, “You can’t believe how much you can get done in a short amount of time until you have kids.”

TM: Two of the epigraphs that preface Competitive Grieving are attributed to Groucho Marx and Katherine Hepburn—so it’s no surprise that in college you majored in film and visual art. How do you find your knowledge of film and visual art shape your work as a novelist?

NZ: Both mediums are so inextricably linked to my being at this point. I grew up on the Upper West Side with a visual artist father and contemporary curator mother. I spent my early childhood running around performance art events in Soho when it was still a dilapidated pit (which is to say, there was not yet a J. Crew), and wandering MoMA’s galleries alone while the museum was closed to visitors. My parents’ friends were all freaky but serious artists and writers. And my older sister was born obsessed with performance and currently runs a theater incubator called The Mercury Store. So discussions around this kind of creative work—and even having “important work”—were the entire backdrop of my childhood.

As for film, I worked as a development exec in LA before I became a writer and married a filmmaker-cum-graphic novelist. Even my in-laws are documentarians! So, my intense exposure to all of this art (high-low and in so many forms) no doubt shapes everything I do from the ground up. Honestly, the really crazy thing would have been if I became an accountant or corporate lawyer. That would have been more lucrative, in retrospect.

TM: You wrote two novels prior to Competitive Grieving, Will You Won’t You Want Me? and Semi-Charmed Life. How did the experience of writing Competitive Grieving compare to your previous novels?

NZ: The year I started writing Competitive Grieving was so overwhelming. Trump had just taken office, I was pregnant with my second child, I had a toddler, my best friend died, my uncle died, I had a big birthday (don’t worry about it!). That’s all to say that I have little to no memory of writing this book. Maybe it’s because it was so linked to my mourning process too. I wrote my first novel during National Novel Writing Month and, for me, the best process is still always to dump a first draft quickly, so I can go back in and get to the nitty-gritty. I do know that, because of the circumstances of having a newborn and a toddler, I wrote this one in small chunks—even writing an entire chapter on my phone in the car on a road trip while the kids slept.

TM: Do you have any recommended reading for those working through grief right now?

NZ: I think different people probably need different things, and at different points in the process. I do think there’s such thing as too soon. When feelings are so raw at the beginning, I imagine most of us need to hide in distraction and escape—anything but thinking about the actual loss. But, whenever one is ready, some of my person favorite books about loss are This Is Where I Leave You, Beach Read, The Year of Magical Thinking, A Man Called Ove, The Great Believers, and, most recently, Crying in H Mart. The J.D. Salinger short story “A Perfect Day for Banana Fish” is maybe my favorite of all time. Again, for me, a mix of humor, pathos and raw honesty is the pinnacle.

NZ: I think different people probably need different things, and at different points in the process. I do think there’s such thing as too soon. When feelings are so raw at the beginning, I imagine most of us need to hide in distraction and escape—anything but thinking about the actual loss. But, whenever one is ready, some of my person favorite books about loss are This Is Where I Leave You, Beach Read, The Year of Magical Thinking, A Man Called Ove, The Great Believers, and, most recently, Crying in H Mart. The J.D. Salinger short story “A Perfect Day for Banana Fish” is maybe my favorite of all time. Again, for me, a mix of humor, pathos and raw honesty is the pinnacle.