For the residents of El Eco, the rural hamlet that gives Tatiana Huezo’s new film its name, life and death are inseparable — not in an abstract sense, but in the here and now, the day-to-day. Animals must be herded and cared for and sometimes slaughtered, crops planted and harvested, and schoolchildren are often right on the frontline with their parents, watching, learning, doing. Taking it all in, they’re smart and inquisitive, kids at their most unself-conscious and open, and with Ernesto Pardo’s extraordinary camerawork holding them close, you might find it hard to let them go. You might wish that Huezo would perhaps return for a follow-up, a Mexico-set spin on Michael Apted’s indelible Seven Up films.

After delving into narrative for the first time with Prayers for the Stolen, the Mexican-Salvadoran filmmaker returns to her nonfiction roots with this intimately observed exploration of tough and tender realities. The Echo focuses on three families, three generations of females in particular, in the evocatively named El Eco, in the state of Puebla. It’s about 10 miles from the nearest town, Chignahuapan, and a couple of hours from Mexico’s capital. And yet the village feels uncommonly remote, its green expanse tucked into a world that’s in full sync with the seasons. The action flows with the rhythms of play and labor, joy and grief, thanks to sensitive editing by Lucrecia Gutiérrez Maupomé and Huezo and the sound team’s evocative work.

The Echo

The Bottom Line

A resounding achievement.

Venue: Berlin Film Festival (Encounters)

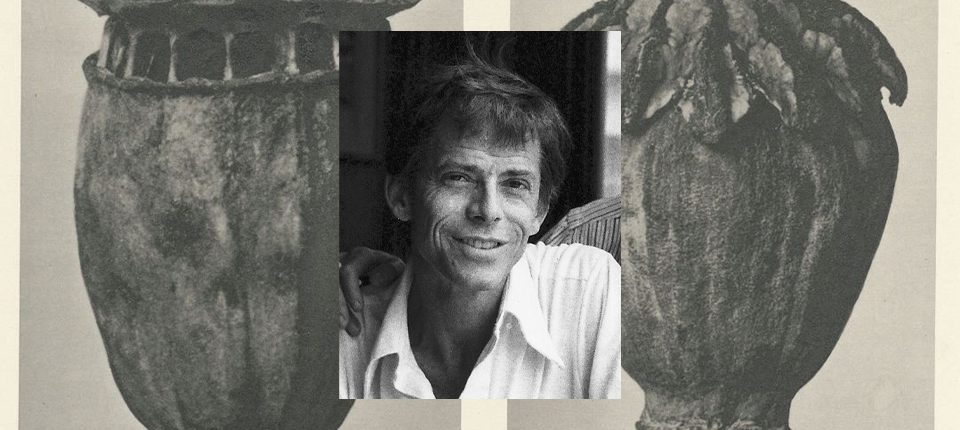

Director-screenwriter: Tatiana Huezo

1 hour 42 minutes

Whatever the reason for the village’s name, echoes of the visual and thematic sort are woven into the doc itself. The motif of water binds the two sequences, potent and eloquently lensed, that open the film. A woman and her children, tween Luz María, known to all as Luz Ma, and her younger brother, Toño, race to rescue a flailing lamb from a pond. Next, inside a house, a woman and her teen daughter bathe the elderly Abuela Angeles. “She’s your responsibility now,” the mother tells Montse (Montserrat Hernández Hernández), words of the deepest respect. It’s a responsibility the girl takes seriously and, as the film proceeds, it’s clear that the bond with her grandmother is one she cherishes.

Then there’s Sarahí, a born instructor if ever there was one. The time Huezo spends with the younger kids in their primary school classroom and with Montse in high school is time well spent, offering profound delights. But the tutoring begins with Sarahí playing teacher at home, presenting a lesson on the extinction of species to her dolls and stuffed animals. Later, in actual classrooms, she brings the utmost conviction and animation to one-on-one science instruction with another student. And as for her lesson on the Mexican Revolution — to two kids barely old enough to read — well, it’s a marvel of concision, complete with handouts and safety scissors. The Echo shows too that the injustice Zapata rose up against isn’t mere history to an observant kid; Sarahí has seen grown-ups being paid the equivalent of $13 for seven hours of farm work.

As in Prayers for the Stolen, Huezo is interested in matrilineal bonds and female strength and courage. The women raising children in El Eco, or at least those we see in the film, are on their own a good deal of the time while the men work elsewhere, and they’re endlessly busy on the home front and in the fields. Abuela Angeles was the first woman to move to El Eco, before she was married and chores took over: “I eventually gave up singing,” she recalls.

The division of labor apparently interests the watchful Luz Ma, who senses the tension between her parents and surprises her mother with questions about why she married at 14 and whether she wants another baby. Consider the silent explosion of Luz Ma’s reaction when her father tells her brother at the dinner table: “Leave your plate. Men don’t wash dishes. That’s what women are for.” A carpenter who’s working on the construction crew of an apartment building — 17 stories tall, much to the wide-eyed Toño’s amazement — he doesn’t understand when his wife asks him to “be more present” for his family. In his mind, they’re each playing their prescribed role, and she’s struggling to convince him that her work matters as much as his.

In El Eco, sequestered tradition and an awakening to the wider world are both alive. It’s a place where some women still warn their children about shape-shifting, baby-killing witches and the need to ward them off with scissors in a hat or prickly pears on the roof. And it’s a place where teenage Montse, a devoted and agile horsewoman, plans to defy her mother by entering a local race, and talks of joining the army because she doesn’t want to “wait for someone to always provide for me.” On the day of that race, Montse isn’t where she imagined herself, and her reaction to the circumstances attests to the power of the filmmaking; Huezo has captured who each of these people are so well, Montse especially, that no words are needed to understand what they’re not saying in intense moments like these.

That’s true too when the kids are sitting vigil with an ailing grandmother. As in the recent documentary What We Leave Behind, the picture of multigenerational family ties and a loving, unflinching embrace of the elderly and the dying is deeply moving. We should all be as cared for in our old age as the abuelos and abuelas of rural Mexico. Huezo captures another sort of communal vigil, another act of caretaking, when the village men descend on the night forest, watching for the timber poachers who have been cutting down and stealing trees by the truckload.

In the face of interlopers and climate challenges, the hardy residents of El Eco keep on keeping on, and in its youngest generation The Echo finds a vibrant mix of complex inheritance and newborn horizons. “Work is work,” a father tells his daughter as he shows her how to clear a cornfield. “It’s not easy,” he adds. “You have to do it with love.” In this clear-eyed and warmhearted chronicle, Huezo and her collaborators have done precisely that.