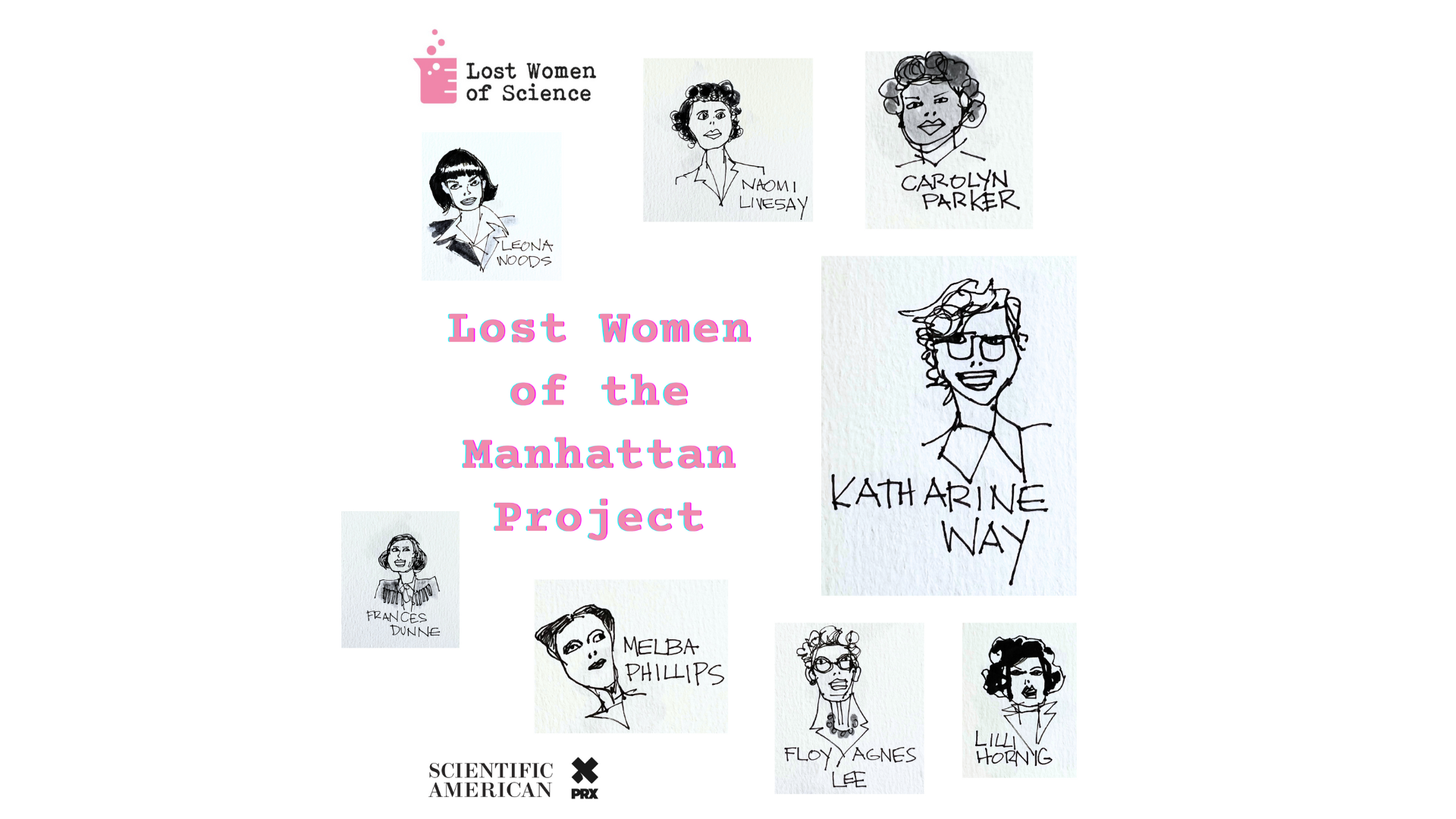

Back in September 2021, a friend sent me a paragraph-long notice in a magazine, reporting that Hollywood director Christopher Nolan was working on a film about J. Robert Oppenheimer. This was disturbing news to me, a co-author of American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, a 720-page biography of Oppenheimer that was published in 2005 and won a Pulitzer Prize in 2006. My co-author, Martin J. Sherwin, and I had never heard from Nolan.

But we had long hoped that our Oppenheimer biography might someday be turned into a film. Even before the book won the Pulitzer, a major Hollywood director had optioned the biography. Initially, we were thrilled. When we won the Pulitzer, the director sent us a bottle of French champagne. A script was written. But nearly four years later, a prestigious studio turned down the script, and the project was abandoned. When Marty and I were finally allowed to read the screenplay draft, we understood the problem: The script was flat and downright boring. The scriptwriter had attempted to tell Oppenheimer’s entire life story from childhood through his early death from esophageal cancer at the age of 62.

American Prometheus was optioned again in 2010 and a third time in 2015. Two more screenplays were drafted. The third one was so terrible that Marty and I felt compelled to draft a memo listing the 108 historical inaccuracies sandwiched into a script that featured a poet/ghost as narrator. By 2021, Marty and I had concluded that Hollywood was just not up to grappling with the complexity of Oppenheimer’s story or the existential issues surrounding the dawn of the atomic age.

But then in September 2021, soon after reading about Nolan’s Oppenheimer project, I got a call from Charles “Chuck” Roven, a producer who had worked on several Nolan films. He assured me that Nolan’s new project was indeed an adaptation of our book. The next day, I found myself speaking with Nolan on the phone. Later, he invited me to meet him in a Greenwich Village boutique hotel.

In our first meeting, Nolan explained that he had already written a script on spec. He hadn’t contacted us because he first wanted to see if he could tackle a script based on such a complicated biography. I eventually learned that in March 2022, Dave Wargo, the MIT-trained physicist who had last optioned the book, had flown out to Hollywood and managed to get the book into the hands of Roven. Soon afterward, Nolan read the book, and he spent the next five months trying his hand at a script.

Nolan said it was long — too long — and he was not prepared to share it with us yet. But he was prepared to answer our questions about what was in the script and what was not.

To begin on a light note, I asked him if he had managed to use Oppenheimer’s favorite toast for his potent gin martinis: “To the confusion of our enemies!” Nolan laughed and said that the toast had been in the script, but he had recently cut it out for reasons of space. He explained that he would lose artistic control if the film went longer than three hours.

I was still skeptical. But over the course of a two-hour conversation, my wife, Susan, and I came away with a sense that Nolan’s script might have promise. I explained that Marty and I had always believed that what had happened to Oppenheimer after he built the atomic bomb was essential to the story. Nolan responded that, yes, he agreed, and assured us that the 1954 trial, the kangaroo court of a security hearing, was featured heavily in his screenplay.

We left this first meeting impressed with Nolan’s intelligence and charm. Regrettably, Marty had been too ill to travel to New York that day. But I reported back to him that maybe, just maybe, Nolan was going to succeed where others had failed. Sadly, two weeks later, Marty died of small-cell lung cancer. He never had a chance to meet with Nolan in person.

Several months later, Nolan shared the finished script. It took me four hours to read it — and I was astonished by both its complexity and emotional intensity. He had captured Oppenheimer’s enigmatic personality, but he had also been faithful to the historical narrative. I found one small inaccuracy — but as I started to explain it, Nolan interrupted me and said, yes, he was aware of it and was trying to figure out how to fix it. (He did.)

I then asked him about the mystery witness who appeared in Lewis Strauss’ Senate confirmation hearing. This was a scene near the end of the film, and I did not recognize the scientist (played by Oscar winner Rami Malek). Nolan responded that he had been curious to know more about why Strauss had lost the 1959 confirmation — so curious that he had taken the trouble to track down the transcript of the Strauss confirmation hearing. This was something that Marty and I had not done. In our book, we had reported the outcome of the confirmation hearing, but we had not bothered to read the transcript. Nolan did — and he found in it the dramatic testimony by “scientist X” that is featured at the end of his film.

I was impressed. Nolan had done his own historical research.

When I finally saw the finished film, I was even more impressed. Nolan and his producer and wife, Emma Thomas, walked me into an empty Imax theater and sat me in the exact middle of the screening room, and then they adjourned to the end of the aisle, leaving me to watch the film in complete privacy. At times, I wept, partly moved by the images, but also for Marty’s absence. And when it was over, I walked over to Nolan, hugged him and whispered, “It is brilliant.” I then turned to Emma and said, “Usually, the author says the book is always better than the film. But in this case, I fear that some will say the film is better.”

I am still not sure.

Kai Bird is a Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer and the director of the Leon Levy Center for Biography.

This story first appeared in a February stand-alone issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.