A torn membrane around the brain might not sound like a major surgical complication, but it is. When the dura mater tears during neurosurgery, whether accidentally or intentionally, cerebrospinal fluid can leak out. The incidence rate is roughly 32 per cent, and the consequences range from delayed wound healing and persistent headaches to meningitis or arachnoiditis.

Achieving what surgeons call watertight dural closure is critical. Yet the current approaches all have drawbacks.

Sutures remain the gold standard, but they’re time-consuming to place and each needle puncture potentially damages the dura further. Tissue adhesives seemed promising until surgeons discovered their tendency to swell excessively after application, creating what’s known as a mass effect. That’s dangerous pressure on the brain. Glue-based sealants also have an unfortunate habit of flowing freely into areas where they shouldn’t go, potentially penetrating into the central nervous system.

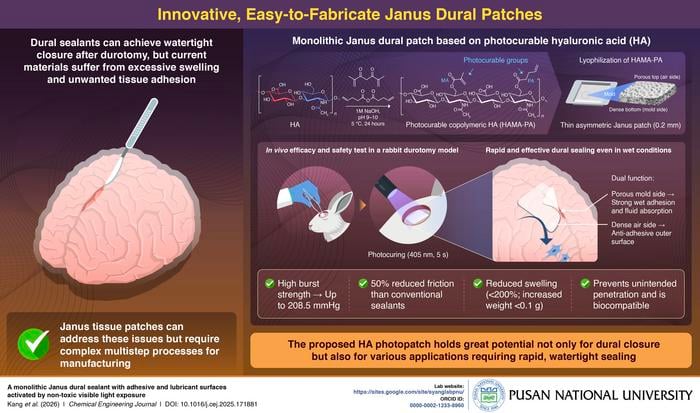

Seung Yun Yang and colleagues at Pusan National University in South Korea have developed a different approach: a patch made from photocurable hyaluronic acid that bonds to wet tissue after just five seconds of visible light exposure.

The material is based on hyaluronic acid, a natural biopolymer already present in many soft tissues. Yang’s team chemically modified it by attaching photocrosslinkable groups to the polymer backbone. Two types: methacrylate and 4-pentenoate. When exposed to 405-nanometre violet light, these groups rapidly link together, transforming the material from a flexible patch into a firm hydrogel.

The fabrication process creates what’s called a Janus structure. That means two different faces with distinct properties. The researchers dissolve the modified hyaluronic acid in water, pour it into moulds, then freeze-dry it. During lyophilisation, the surface exposed to air becomes relatively dense, whilst the surface touching the mould remains porous. They then compress the patches to roughly 0.2 millimetres thickness.

That asymmetric structure proves useful in practice. The porous side rapidly absorbs blood and tissue fluid, creating intimate contact with the wound surface. This takes about 20 seconds. The partially dissolved hyaluronic acid infiltrates the micro-rough structures of the tissue. When violet light hits the patch, photocrosslinking occurs and the material solidifies into a hydrogel that interlocks mechanically with the tissue.

In laboratory tests using punctured collagen sheets, meant to mimic the dura mater, the patches achieved impressive results. Burst pressures up to 208.5 mmHg when the porous side faced the tissue. That’s roughly ten times greater than typical intracranial pressure, which sits around 16 mmHg. Commercial fibrin sealant Tisseel and liquid versions of the photocurable hyaluronic acid both performed poorly by comparison, unable to seal effectively because they flowed through the holes.

The adhesive strength was substantial as well. When used to bond two collagen sheets together, the patches showed adhesion strengths of 31 kilopascals using the porous side. Nearly tenfold higher than Tisseel’s 2.9 kilopascals.

The dense outer surface has its own advantages. It forms a smooth, lubricating barrier that reduces friction by roughly 50 per cent compared to commercial sealants. This matters because postoperative tissue adhesion causes complications. Healing surfaces can stick together inappropriately, leading to chronic pain, nerve damage and bleeding.

Laboratory tests showed the patches also resist cell attachment. When fibroblasts were cultured on the photocured patch surfaces, the cells struggled to adhere and failed to spread properly, appearing round rather than elongated. This anti-adhesive property comes from hyaluronic acid itself, which has a high negative charge and strong hydration layer that together inhibit protein adsorption and cell attachment.

Weight matters in neurosurgery, where any additional mass pressing on the brain is undesirable. The patches showed less than 200 per cent swelling by weight when immersed in physiological fluid. That’s considerably better than existing products like CoSeal, which swells by roughly 560 per cent, or DuraSeal at approximately 200 per cent.

The team tested the patches in rabbits with induced dural tears. After hydration with saline, mimicking the wet conditions during actual surgery, and five seconds of light exposure, the patches sealed effectively. Four weeks later, examination revealed the skull and dura mater had repaired without postoperative adhesion to surrounding tissue. The patches had completely biodegraded, and there were no degenerative changes like necrosis or inflammation in the skull, dura or nearby brain tissue.

Safety questions naturally arise around the degradation products. The photocrosslinking process creates chemical bonds between the attached groups, which eventually break down through hydrolysis in the body. To assess this, the researchers administered potential breakdown compounds to rats intravenously. The substances cleared rapidly from the bloodstream, with half-lives ranging from roughly 21 to 77 minutes depending on the compound. Most was excreted through the kidneys. Twenty-four hours after administration, none of the compounds remained detectable in plasma or tissues including brain, liver, lungs, kidneys, spleen or ovaries.

SNvia, a biotechnology company and subsidiary of Pusan National University, has licensed the technology and established manufacturing facilities for the photocrosslinkable hyaluronic acid. They call it PhotoQ-HA. According to the press release, preclinical studies are expected to conclude in the first half of 2026, with a clinical trial application to South Korea’s Ministry of Food and Drug Safety planned for the same timeframe.

The applications might extend beyond neurosurgery. The material’s strong adhesion to wet tissues suggests potential uses in drug-delivery patches, cell-laden constructs for tissue engineering, and artificial tissues. But for now, the immediate clinical benefit is clear: rapid wound sealing that reduces the risk of cerebrospinal fluid leakage after dural tears.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!