In interviews with CNN, doctors who work in the fertility field, and academics who study the legal landscape around it, say there is grave uncertainty — both about how abortion laws already on the books will be interpreted and about how lawmakers and local prosecutors may seek to push the envelope, freed from the precedents that have effectively shielded the fertility process from government meddling. That lack of clarity, it is feared, will affect the treatments doctors are willing to offer IVF patients and the decisions people will have to make about how to pursue growing their families.

There are multiple stages of the fertility process that — without the Supreme Court’s current legal protections for abortion rights, which have been in place for 49 years– could be vulnerable to government interference, according to Seema Mohapatra, a law professor at SMU Dedman School of Law who specializes in assisted reproduction.

“It really does have these practical effects where, because of the lack of protection of Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, you actually might not be able to have this wanted child that you’ve been paying all this money and going through this physical process in order to have,” she said.

“We are dangling in the wind right now,” one Midwestern reproductive endocrinologist told CNN about the uncertainty looming. The doctor spoke on condition of anonymity because of the sensitive nature of their practice and the uncertain future of procedures like IVF in their state.

“States have already taken the liberty of having these expansive definitions. They just couldn’t really enforce them the way they wanted to because Roe and Casey stood in the way,” Rutgers Law School Dean and professor Kimberly Mutcherson said, referring to the 1973 and 1992 Supreme Court abortion precedents. But if Roe and Casey are overturned, Mutcherson said, that would effectively be the Supreme Court saying: “Do what you want to do, states!”

“And that’s a pretty wild place to be in,” she said.

“A bill like the one that’s proposed in Louisiana would prohibit IVF in that state, and that’s something we’re extremely worried about,” Dr. Natalie Crawford of FORA Fertility in Austin, Texas, told CNN. “We don’t think people understand the repercussions from some of these proposed bills.”

‘It’s a process of conception, not a moment’

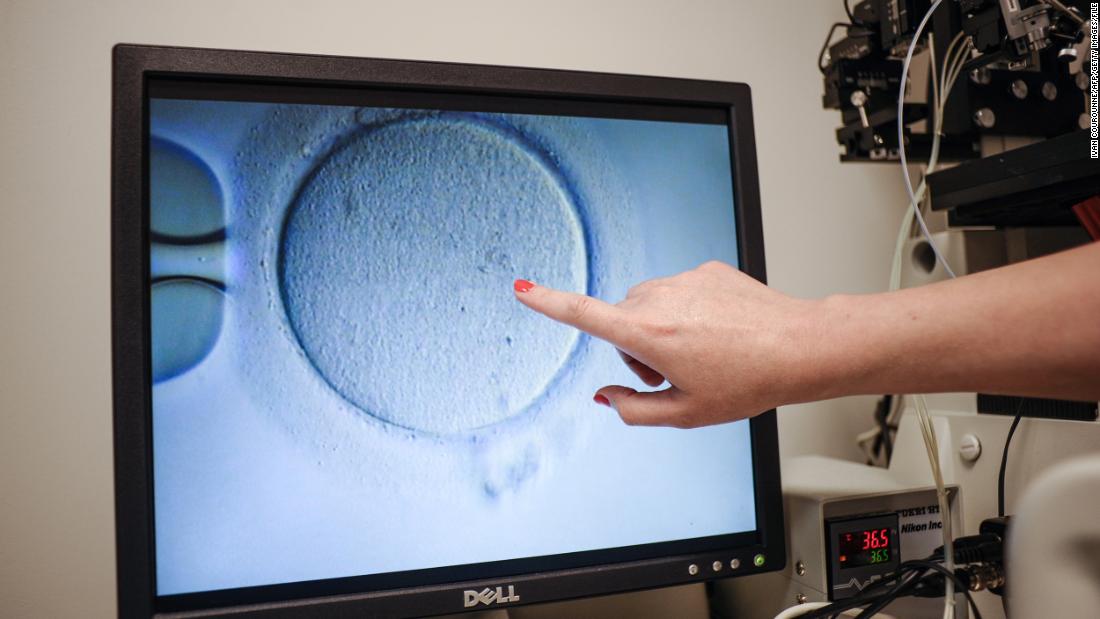

When an individual or couple undergoes the IVF process, the work begins in a lab, where a sperm fertilizes an egg after weeks of preparation. The goal is to ultimately transfer a healthy embryo into a person’s uterus. But first, the embryo must grow to blastocyst stage, which typically occurs between five and seven days after fertilization.

“It’s a process of conception,” the Midwestern doctor said. “Not a moment.”

IVF clinics typically use two people’s genetic material to create multiple embryos because they don’t know which ones will grow to the right stage or which ones will result in a successful pregnancy.

“The goal is generally to make as many embryos as possible,” the doctor explained. “That’s because, on average, half of all embryos are chromosomally abnormal.” These abnormalities can result in conditions like Down syndrome and trisomy 18 or may prevent the embryo from becoming a healthy pregnancy. Clinics and/or clients typically choose to discard them rather than implant them.

That creation of multiple embryos is where IVF clinics see potential legal trouble on the horizon. If a state defines an unborn child as existing at the moment of fertilization, clinics could violate the law by discarding chromosomally abnormal embryos or by terminating a pregnancy where multiple embryos have been implanted.

“The chances of a successful IVF cycle aren’t that high, so doctors will often implant multiple embryos to maximize the odds at least one pregnancy comes to term,” said Mary Ziegler, a visiting Harvard Law professor who writes extensively on abortion issues. “Sometimes, to maximize the chances a pregnancy comes to term, some of those pregnancies are terminated. A lot of people in the anti-abortion movement look at that and say that’s abortion.”

Individuals who undergo IVF may also choose to freeze unused embryos for later use, or for backup if a pregnancy is ultimately unsuccessful.

“There’s always extra embryos,” Mohapatra said. “You don’t know if it’s going to take on the first cycle.”

Crawford posted a lengthy thread on Twitter highlighting how restrictive abortion laws in several states could be detrimental to IVF, explaining that the process to “fertilize eggs, freeze embryos, test embryos, and transfer/discard embryos … is essential for safe, accessible and effective IVF care.” Crawford continued, “The fear is that when Roe is overturned states will then individually decide their stance on this matter … if life begins legally at fertilization — then we are limited in the above technology.”

‘What do I tell these patients?’

There’s no clear indication at this point if individual state legislatures will extend their abortion bans to explicitly apply to the IVF process. But ambiguity in how future abortion bans might be interpreted — particularly in a legal landscape where enforcement decisions could be made by individual prosecutors — is forcing those in the field to scrutinize what is possible.

“If I were at an IVF clinic, we would be wasting a lot of hours debating, ‘What does this mean? What do we have to do? How do we protect our patients?’ ” asked Katie Watson, a bioethicist and lawyer who is an associate professor at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. “So the chilling effect and the limitations on the smart practice of medicine will be significant even if it’s not what legislators intended.”

The Midwestern doctor who regularly sees patients battling infertility says the office phone has been ringing off the hook with people concerned about what a post-Roe world would mean for their reproductive journeys.

“Receptionists have asked me, ‘What do I tell these patients?’ ” the doctor said, adding that it’s been hard to give a definitive answer.

“All it takes in any event is a rogue prosecutor who wants to be aggressive in his or her interpretation of the law, and that could certainly create issues for those seeking IVF,” Kim Clark, senior attorney for Reproductive Rights, Health and Justice at the progressive advocacy organization Legal Voice.

Another complicating factor is what role civil enforcement measures — like the Texas six-week ban, allowing individual citizens to file lawsuits against anyone who facilitates a procedure prohibited by the ban — will play in the post-Roe world.

“When you have these citizen enforcement statutes, suddenly any random neighbor who says a blastocyst is a [person] can sue that clinic, and that’s where the chilling is phenomenal,” Watson said.

One thing is clear, however. If Roe is erased, an array of measures targeting IVF could “much more easily move forward,” according to Judith Daar, the dean at Northern Kentucky University-Salmon P. Chase College of Law, who formerly chaired the ethics committee for the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

“The reversal of Roe could motivate and certainly pave the way for new legislation that could specifically target IVF,” she said, while suggesting that states could, for instance, eventually ban the genetic testing that is now regularly performed on embryos to spot abnormalities before they’re implanted.

Mutcherson said fertility patients may seek to take proactive action, like move their embryos out of states expected to be hostile to abortion.

“The question really now is are there things that people should be doing to protect themselves before laws start to change?” Mutcherson said.