“You can play ‘dress up’ or whatever, but why on earth would you post these photos on the internet? People will think it’s weird!”

While this might sound like a parent chastising their young child who got ahold of their iPad, this was a line my dad uttered to me, a queer person in their late 20s at the time, while he was driving me to the airport to fly back to San Francisco after one of my regular trips to Georgia, where I grew up.

I’d grown accustomed to these types of interrogations on my visits home, and just before I left and was trapped in the car for 45 minutes always seemed to be the best time for my parents to express their concern around how California had “changed” me and question where my life was headed. During this particular episode, my dad was sharing his disdain around my newfound hobby: performing in drag clubs as Mary Lou Pearl.

This exchange between us was in stark contrast to how my dad reacted when I first came out as gay over 10 years earlier. For him ― a physician from central Mississippi who has never lived outside the South, except for a brief stint in Oklahoma for his medical residency ― sexual orientation was part of one’s genetic makeup. When he realized I was gay, he assured me that although the road ahead would be tough, and my mom would struggle because of her religious convictions, this is who I was, and he’d support me. In the same breath, he cautioned me to not be one of “those gays,” going on to add that I shouldn’t make anyone feel uncomfortable or throw my sexuality in their face by “wearing women’s clothes or marching in the Pride parade.”

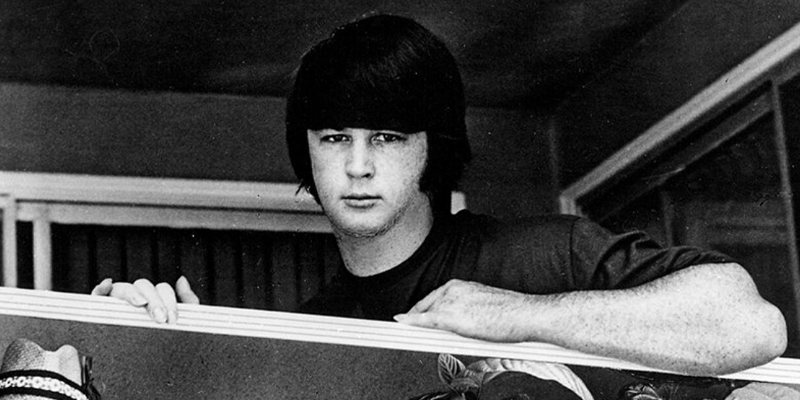

Well, you can probably guess how this turned out. In fact, the heated conversation we were having in the car on that day was sparked by photos that surfaced of me and my then-partner doing drag in the San Francisco Pride parade.

Courtesy of Blake Mitchell

Even though my dad had a supportive stance around queer sexual orientation, I quickly learned that his understanding of gender-nonconforming behavior and queer gender identity was quite limited. And, as such, he was afraid and critical of it.

My dad grew up in a religious, conservative community where, by his own admission, there weren’t any openly LGBTQ+ people. Queerness was spoken about as something evil and of the devil. It was something to be shunned and condemned, and if someone found themselves a “victim of same-sex attraction,” as they’d referred to it, they better pray hard for God to save them.

So, as you can imagine, when I called my parents last year to let them know I’d been vaccinated and was coming home to visit them, I was stunned to learn that my dad wanted me to bring home my drag makeup and put him into drag. He even had a name picked out.

This was a vast departure from our discussions about drag over the four preceding years. Sure, I’d finally convinced my parents to come see me perform back in 2019, but it was clear that my dad was quite uncomfortable, and I suspected he’d mostly done it to appease my mom, who had done some strong lobbying behind the scenes to get him there. When I asked him after the show what he thought and how he felt, he simply replied, “Well, you either evolve, or you die,” then shuffled to his Uber and back to his hotel room.

We’d moved beyond his outright condemnation of me doing drag, but rather than a peace agreement, it had felt much more like a ceasefire arrangement.

“This goes beyond my limits of understanding, but I love you and know you to be a good person, and this seems to make you happy, so I’ll let it go,” he’d said.

We left it at that. The next time I suggested my parents come to San Francisco to see me perform in a drag competition, my mom booked her flight and explained away why my dad wouldn’t be able to join.

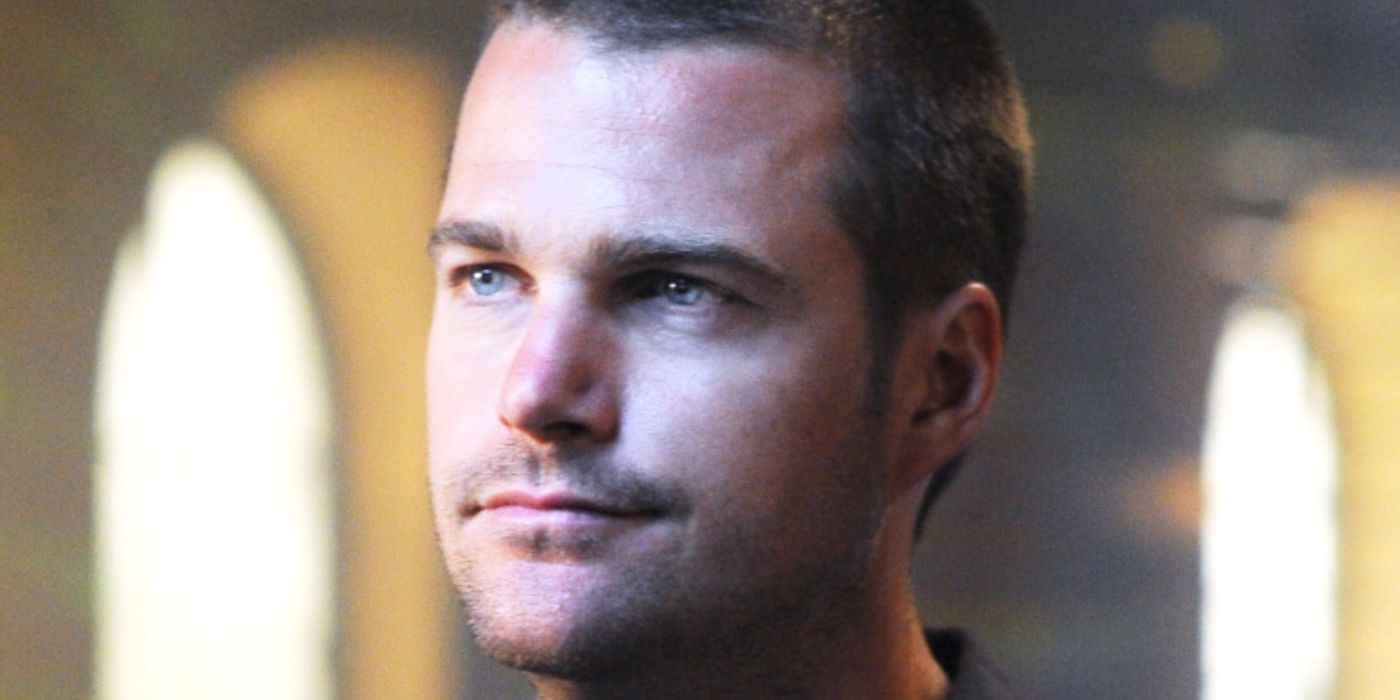

Courtesy of Blake Mitchell

On the trip home to put my dad in drag, I was an absolute bundle of nerves. As we settled into the process of getting him ready, I asked what prompted him to want to get his makeup done this trip. He quipped back, “Well, I’d run out of things on my bucket list,” and laughed about wanting to know what he’d have looked like as a saloon girl in the Wild West. But deep down, I suspected that there must be more to his request.

In digging into my dad’s negative response to me expressing myself in a queer way, I realized he had a lack of understanding around what it meant to do drag or express gender nonconformity versus being transgender or non-binary. I also realized that his exposure to drag, trans and queer culture was extremely limited. It became clear that his earlier comments about me not being “that type of gay” stemmed from a fear of the unknown and a desire to protect his child from the hardship and ridicule he’d seen more queer-presenting people experience when they’d entered his exam room at the hospital. His exposure to positive examples of queer life were limited, and even then, he and my mom both watched many of the queer people around them be impacted by the AIDS epidemic in the ’80s when he started practicing medicine.

As time went on, largely without expressing it to me, he’d come to normalize me doing drag in his own mind. He equated it to me doing theater in middle and high school; the only difference was that now I was dressing up as a woman. Seeing me perform in San Francisco, while uncomfortable, had illustrated to him the love and support that my community had for me and this area of my life, and it brought to light the fun, playful nature of drag that so many people are drawn to in clubs around the world and on television.

As I put him into makeup in my childhood bedroom on Easter Sunday, I watched as he came to experience this joy for himself. We laughed, he told jokes and tried on different accents to go with his drag character. (He chose the name “Daddy Lou Merle,” a play on a name I’d given him, “Daddy Lou Pearl,” and “Merle,” the name of my great aunt who’d been quite the character in her older age, known for gambling, eating jawbreakers and her 1971 induction into the South Dakota Softball Hall of Fame.) At one point, he said the makeup made him feel like he was in the opera and began singing from “The Marriage of Figaro.” As we say in the drag world, he was feeling the fantasy.

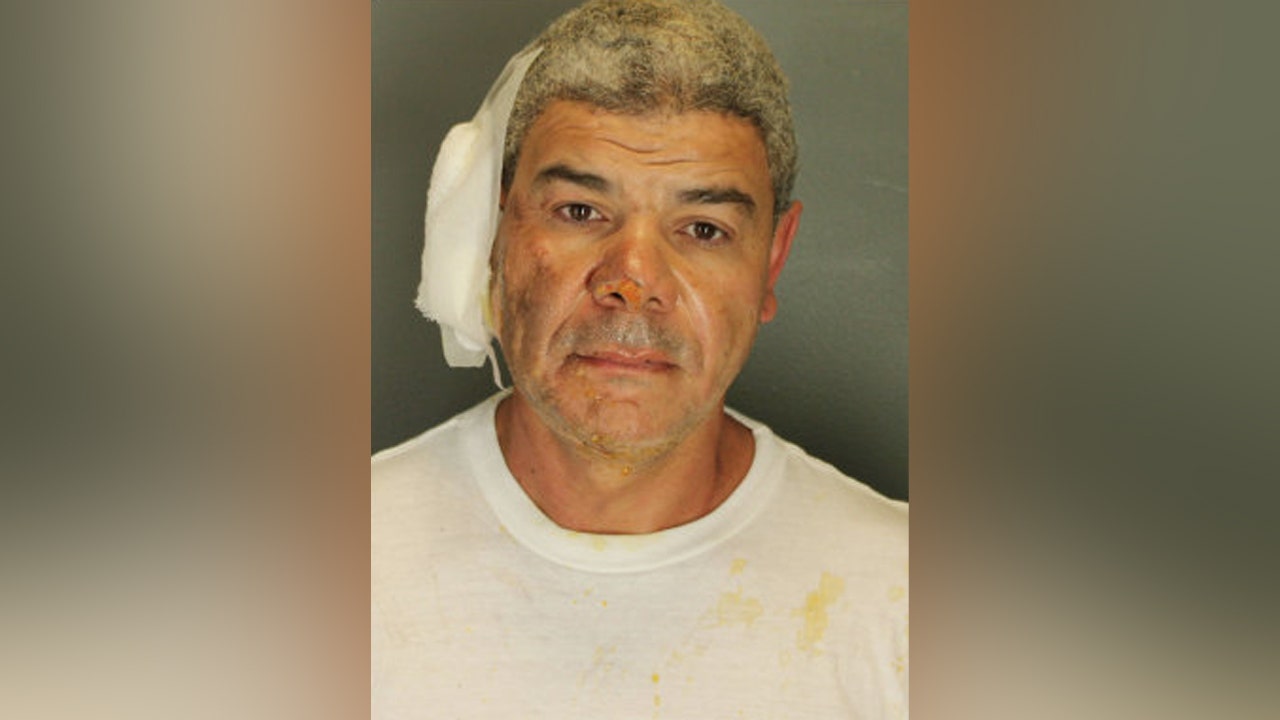

Courtesy of Blake Mitchell

When the final moment of truth came and dad turned the mirror around to see himself, he erupted into excitement. His already Southern accent thickened, and he exclaimed, “Oh, my word ― she is a Southern belle! Oh, my gawd.” Then, in my favorite moment of the day, he turned to my mom, who was sitting on the bed, and said, “Hi, doll!”

It felt as if he was channeling bits of my grandmother, my aunts and the women I grew up meeting at church in his hometown of Columbus, Mississippi. Much like me, he drew from the larger-than-life Southern women (with larger-than-life hair) that he grew up around.

My emotions were mixed as he went through this transformation. Sure, I was happy he was enjoying it and that the experience was positive, but where had this excitement been before? Why had I dealt with so many disparaging comments and fielded so many antagonizing questions for us to wind up here? Why had his attitude changed seemingly so quickly?

As we sat at the kitchen table after he’d wiped off all the makeup, I asked again, “Dad, why did you really want me to put you into makeup?” He shared that as time went on, and he saw how much drag meant to me, he wanted to understand it better. He knew that it was something beyond the reach of his comfort level, given his lived experience and where he grew up, but he wanted to try and meet me halfway.

Courtesy of Blake Mitchell

As queer people, we talk a lot about wanting for our families and community to accept us. Acceptance lives in the space beyond tolerance, which is defined as “allowing the existence, occurrence, or practice of (something that one does not necessarily like or agree with) without interference.” Acceptance goes a step further and involves the “act of receiving someone and admitting them into your group.” Tolerance says “you can sit here, even if it makes me uncomfortable,” while acceptance says, “I’d love for you to sit with us, you’re welcome here.”

If we take this thought process even further, we arrive at the concept of embracing, which is defined as “holding someone in your arms” or to “accept or support willingly and enthusiastically.” My dad asking me to put him into drag was him taking that extra step into embracing me, meeting me where I was and demonstrating through his actions his love and support for me. This is especially meaningful, given his level of discomfort around drag just a short time before.

As queer people, we’re often expected to explain and defend our identities. While the effort and emotional labor can definitely be productive and lead to change, it’s also taxing and can feel overwhelming. When allies choose to go on this journey of growth and self actualization with us ― and are willing to get uncomfortable and challenge themselves ― it eases things for us and makes bigger change possible. I’m so grateful that my dad made that choice.

And best of all? Now I have a fabulous new drag sister.

Blake Mitchell is a corporate diversity and inclusion professional, drag performer and activist living in San Francisco, California. Originally from Atlanta, Georgia, Blake channels their Southern upbringing into creating their drag persona, Mary Lou Pearl. Blake is an avid supporter of causes surrounding LGBTQ+ advocacy and racial justice including the AIDS/LifeCycle, Brave Trails LGBTQ+ Summer Camp and Showing Up for Racial Justice. Blake identifies as non-binary and genderqueer and uses they/them pronouns.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch.

![[Oops! Corrected Link] Read Harder 2025 Halfway Check-In Survey [Oops! Corrected Link] Read Harder 2025 Halfway Check-In Survey](https://s2982.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/read-harder-2025-check-in-survey.jpg.optimal.jpg)