President Joe Biden, when describing the wacky and extreme element of the modern GOP, has long leaned on a simple phrase: “This isn’t your father’s Republican Party.”

His State of the Union address, delivered Tuesday night, had a slightly different message, this time about his side of the aisle: “This isn’t your father’s Democratic Party. It’s your grandfather’s.”

If President Bill Clinton used his 1996 State of the Union speech to declare the end of the era of big government and President Barack Obama used his to endorse “bipartisan” changes to Social Security and a controversial free trade pact with Pacific Rim nations, Biden used his speech to declare the return of the old populist Democratic Party, explicitly aligned with the middle class and willing to call out entrenched economic power.

The speech did not represent a turn to either the center or the left, a full-on commitment to bipartisanship or an announcement that he would rely on executive action. What it did represent was a framing of the past and future of Biden’s presidency aimed squarely at working-class voters in states like Ohio, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, which could determine the success or failure of Biden’s likely reelection bid in 2024 and the fate of the Democratic-controlled Senate for years to come. This is Biden’s effort to reframe the center of American politics.

In recent weeks, Biden has openly courted voters who don’t have a college degree, repeatedly emphasizing how legislation passed during his first two years in office, specifically subsidies to develop semiconductor manufacturing and a bipartisan infrastructure law, will create jobs that don’t require a degree.

“Jobs are coming back, pride is coming back because of the choices we made in the last two years,” Biden said toward the start of his 73-minute speech. “This is a blue-collar blueprint to rebuild America and make a real difference in your lives.”

The major shift in American politics since the election of President Donald Trump has been the rapid movement of voters without a college degree into the Republican Party, handing the GOP a substantial advantage in both the Electoral College and the Senate because of the preponderance of working-class voters in less-populated rural states.

This advantage was gained, in part, by the anti-free-trade economic nationalism Trump ran on in 2016 that once was a mainstay of union politics. Old union towns from Wisconsin to Pennsylvania flipped from Democratic candidates to Trump, handing him a shocking Electoral College win. Biden won many of them back in 2020 but still only won the Electoral College by tens of thousands of votes in a handful of swing states. Now he is making his appeal to them central to the party’s future.

In 2024, Democrats need to hold those voters to deliver Biden a victory. To hold on to their 51-seat majority in the Senate ― where Democrats are up for reelection in working-class-dominated states from Montana to Pennsylvania ― they will likely need to gain ground.

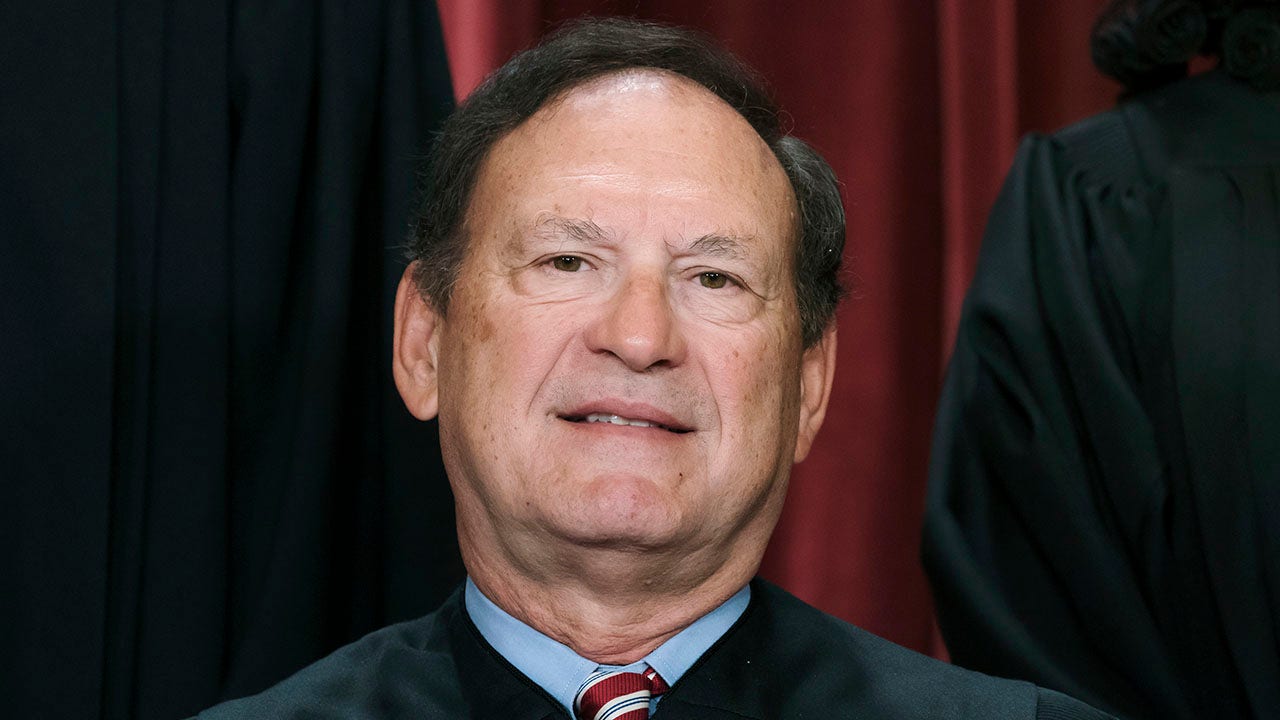

JACQUELYN MARTIN via Getty Images

Felicia Wong, president of the Roosevelt Institute, a progressive think tank, has long argued that Biden’s economic instincts are “pre-neoliberal,” shaped by the Democratic Party of the New Deal before Clinton and his “third way” acolytes moved the Democratic Party closer to big business. On Tuesday night, those instincts were on display.

With a strident economic nationalism, Biden touted a national industrial policy based on returning manufacturing jobs from overseas through the bipartisan CHIPS Act, new construction jobs from the bipartisan infrastructure law and new green jobs spurred by the Inflation Reduction Act. He criticized Big Pharma and Big Tech for jacking up drug prices and allowing children’s privacy to be compromised. He called for stricter antitrust enforcement and derided the junk fees foisted on Americans by heavily consolidated corporations, from cellphone and cable bills, concert tickets and airline policies.

“Americans are tired of being played for suckers,” Biden said.

Biden spoke that line about exorbitant junk fees, but it could be said about the rest of the economic agenda he touted, whether it’s the reversal of decades of economic globalization gutting the country’s manufacturing base or ever-rising prescription drug prices cutting into people’s pocketbooks.

And he pushed this “blue-collar blueprint” without dropping Democrats’ commitments to civil rights or women’s rights, touting the passage of the Respect for Marriage Act and calling for police reform in the wake of the Memphis police killing last month of a Black driver, Tyre Nichols, and the restoration of abortion rights that were stripped away last summer by the conservative Supreme Court.

Biden gave a 21st century take on Hubert Humphrey liberalism ― full employment, labor unionism and social justice ― and not the free market liberalism that has dominated the party for the past 30 years.

The clearest contrast Biden drew with Republicans, during a speech heavy on bipartisan overtures, may have been on taxes: With Congress passing a minimum tax rate for corporations last year, he proposed a similar minimum rate for billionaires. He also suggested quadrupling a new tax on stock buybacks ― when corporations buy up existing shares of stock to drive up the stock price, a step that often rewards investors at the expense of workers.

“I think a lot of you at home agree with me that our present tax system is simply unfair,” Biden said. “No billionaire should pay a lower tax rate than a schoolteacher or firefighter.”

As Biden delivered broadside after broadside at corporate America’s power, he signaled a break with 30 years of an orthodox, laissez-faire approach to antitrust enforcement that has allowed corporate consolidation to run wild.

He called on Congress to pass “bipartisan legislation to strengthen antitrust enforcement and prevent big online platforms from giving their own products an unfair advantage,” marking the first use of the word “antitrust” in a State of the Union speech since 1979.

In emphasizing his administration’s war on what it called “junk fees” ― the fine-print charges that take billions of dollars out of American consumers’ wallets, he said, “Junk fees may not matter to the very wealthy, but they matter to most folks in homes like the one I grew up in. They add up to hundreds of dollars a month.”

For nearly two decades, Democratic presidents and lawmakers had been running on empowering Medicare to negotiate lower prescription drug prices. Thanks to the policy’s inclusion in the Inflation Reduction Act in August, Biden is the first Democratic president who can take credit for actually achieving this change in his annual address to the country.

Tom Williams via Getty Images

He also promised to expand another new prescription drug benefit that he enacted ― a cap on Medicare beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket insulin costs ― to all Americans.

But perhaps most surprising was the plain language he used to describe how the drug companies gouge patients who need insulin to keep their diabetes under control. He became the first president in U.S. history to use the frequently pejorative phrase “Big Pharma” to describe the pharmaceutical industry in a State of the Union address.

“It costs the drug companies roughly $10 a vial to make that insulin. Package and all, you may get up to $13,” he said. “But Big Pharma has been unfairly charging people hundreds of dollars ― $4-500 a month ― making record profits. Not anymore!”

In one of the more memorable moments of Biden’s speech, he got into a spontaneous back-and-forth with Republican members of Congress who objected to his claims that some of them want to phase out Social Security and Medicare.

“Instead of making the wealthy pay their fair share, some Republicans … want Medicare and Social Security sunset,” he said, prompting immediate boos from Republicans. “I’m not saying it’s a majority.”

As the booing persisted, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) yelled out, “Liar,” but Biden held his ground.

“Contact my office,” he said. “I’ll give you a copy ― I’ll give you a copy of the proposal.”

He went on to declare his willingness to accept that those Republicans had changed their minds.

“So folks, as we all apparently agree, Social Security and Medicare is off the books now,” he said.

Biden did not sketch out a plan for shoring up Social Security and Medicare that precludes benefit cuts of any kind. But his mere decision not to endorse the need for compromise or bipartisan cooperation to change the program marked a major departure from his immediate Democratic predecessor.

Barack Obama repeatedly sought to strike a “grand bargain” with Republicans on fiscal policy that would combine Social Security cuts with new revenue, including during late talks to avoid a “fiscal cliff” of automatic spending cuts. In one instance, Biden even served as Obama’s negotiator in those discussions.

In his State of the Union speech in 2013, Obama pushed back on the idea that Social Security cuts alone could reduce the deficit but instead called for them to be balanced by tax increases on the rich.

“We can’t ask senior citizens and working families to shoulder the entire burden of deficit reduction while asking nothing more from the wealthiest and the most powerful,” Obama said.

Speaking about the need to confront climate change, Biden kept the focus on jobs, especially union jobs, noting that the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers would deploy tens of thousands of workers to build 500,000 electric-vehicle charging stations across the country.

“Lowering utility bills, creating American jobs and leading the world to a clean energy future,” Biden said, aiming to sum up his climate approach without deploying any of the occasionally apocalyptic rhetoric sometimes favored by the climate-centric left. He also acknowledged the country would continue to need oil and gas “for a while” ― a line that will disappoint climate hardliners.