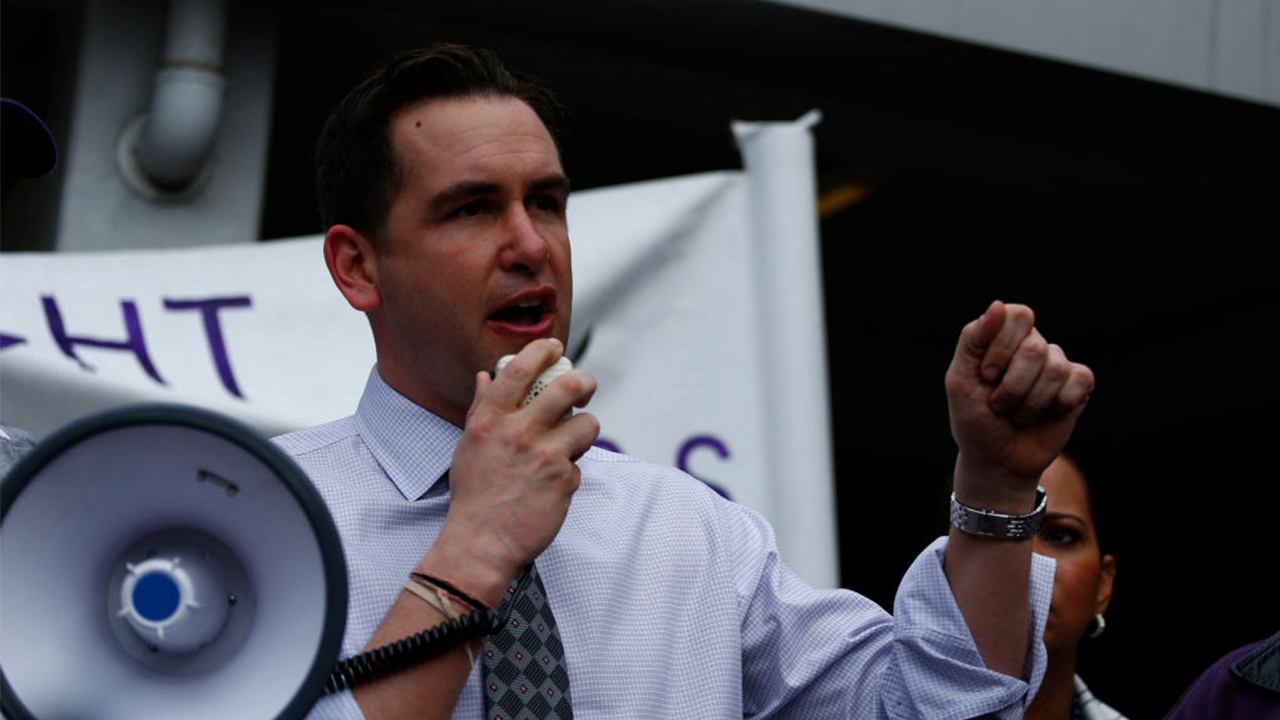

In the run-up to the 2020 presidential election, there was significant chatter that Jason Kander would run for the Democratic nomination.

Kander, a former intelligence officer in Afghanistan, served in the Missouri House of Representatives and then as the state’s secretary of state. In 2016, he lost the U.S. Senate election to Republican incumbent Roy Blunt ― but significantly outperformed presidential candidate Hillary Clinton in the state.

In 2017, in a final Oval Office interview, President Barack Obama was asked about the future of the Democratic Party. He named Kander.

That same year, Kander started a political group called Let America Vote, dedicated to ending voter suppression.

Yet behind the scenes, Kander was struggling. He had been suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder since his return from Afghanistan ― which was a secret he kept from everyone, including himself.

Instead of running for president, Kander made the surprise announced in June 2018 that he would instead be throwing his hat in the ring for mayor of Kansas City, Missouri. He was widely seen as the favorite in the race, which is why in October it was even more shocking when he said he was dropping out.

Kander then revealed for the first time publicly that he had been struggling with mental health problems, including depression, nightmares and suicidal thoughts. He removed himself from public life and sought help.

Since that time, Kander has continued to speak about mental health, worked with veterans and dipped his toe back into Democratic politics.

He is out with a new book, “Invisible Storm: A Soldier’s Memoir of Politics and PTSD,” which hits shelves on July 5. An exclusive excerpt provided to HuffPost is below.

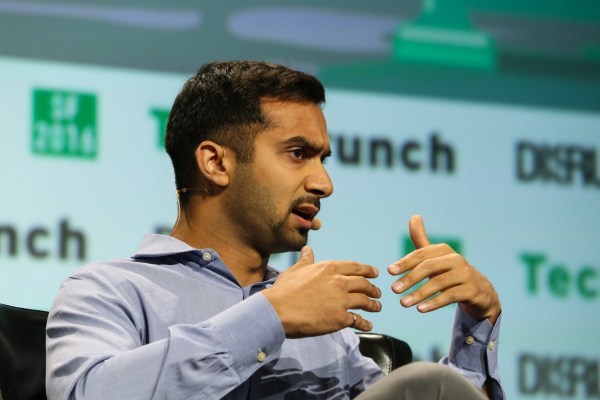

Adri Guyer/Adri Guyer Photographer

Sometimes the journey to rock bottom begins at the very top. For me, the trip down even included a layover in paradise.

After New Hampshire, Senator Brian Schatz arranged for me and my family to come to Hawaii to give a speech, and the Hawaii Dems put us up in a resort for a few days. To my surprise, I felt safe there, safer than I had in a long time. I slowed down. I ignored my phone. I ran on the beach. I taught True to swim. I lay next to Diana while we both read books.

I tried to take stock. I realized how exhausted I was. I’d been living like this for so long that I didn’t remember it hadn’t always been this way.

The sensation of being constantly in danger I’d brought home from Afghanistan wasn’t gone, but it was softer. It had been so, so long since I had felt anything but guilt and fear, so long since I’d let my guard down.

Over the recent months, I’d been hinting at how exhausted I was, but lately things had gotten worse.

I was numb to the highs of the campaign trail. It was like I was having an out-of-body experience, watching Jason Kander walk into donor meetings and give speeches. I was having more and more trouble concentrating. Maybe it was the sleep deprivation brought on by the night terrors, maybe it was something more, but I was beginning to have thoughts that frightened me. It wasn’t that I was suicidal, it was more like I was coming to understand why some people chose suicide. All I knew was I didn’t want to feel like this anymore. I was afraid of what might happen to me if I kept going, but I was even more terrified of what might happen if I stopped.

People often ask me what finally caused me to get help. Just like there was no single moment of trauma that caused this trouble in the first place, there was no single event that caused me to reach for real help.

For a few weeks, an obscure notion had been circling in my mind: I was at some sort of crossroads. It often manifested as a line from the movie The Shawshank Redemption: “Get busy living or get busy dying.”

“You have to be a little crazy to be in politics, but what you cannot be is mentally ill.”

One night at the end of September, after yet another stressful day of simultaneously running for mayor and leading Let America Vote, I felt I had hit a new low—a sense that whereas things had been getting steadily worse for years, now for a few months they’d been getting worse even faster, which was frightening. Sitting next to Diana on the couch in our living room, I was struck by the idea that it was time to try anything.

I was still holding on to the idea that perhaps I could stop the problem where it was—or at least escape the increasingly common feeling that if I stopped existing, things would be better for everyone.

This thought process—like a tiny seedling of hope sprouting through a crack in the pavement of depression—had been percolating for a couple of weeks. That’s why I’d already looked up the number for the Veterans Crisis Line.

You have to be a little crazy to be in politics, but what you cannot be is mentally ill. Or at least, that’s how it seems if you look back at the past few hundred years of American government (which started as a rebellion against a king who was mentally ill). Even a suspicion that a candidate or someone in government has a psychological problem is a death sentence in politics. Just look at Thomas Eagleton. He was a political phenom—Missouri attorney general at thirty-one, US senator from Missouri at thirty-nine. You might call him another young vet from the Midwest. In the 1972 election, George McGovern tapped him to be his running mate against Nixon.

Laurie Skrivan/St. Louis Post-Dispatch via Getty Images

Then, two weeks after the Democratic Convention, the news broke: Eagleton had been hospitalized multiple times for electroshock treatments for clinical depression.

At first, McGovern claimed he would stick with Eagleton “1,000 percent.” Six days later, he asked Eagleton to withdraw from the ticket. This wasn’t cruelty—prominent psychiatrists, including Eagleton’s own doctors, had told him that the depression could return and thereby put the country in danger. The episode allowed Republicans to claim that McGovern—already painted as a wild-eyed leftie—had crappy judgment. He lost everywhere except Massachusetts and DC. One Democratic strategist called Eagleton “one of the great train wrecks of all time.”

Attitudes toward mental health have changed since then (Mike Dukakis, who also got crushed in a presidential election, is now an ambassador for the value of electroconvulsive therapy)—but they haven’t changed that much. As much as I knew I needed help, I was after all a politician.

The election was just a few months away. I didn’t know what treatment entailed, but I knew I couldn’t do it and run for mayor at the same time. My daily schedule was filled from sunrise to 10 p.m. with meetings, speaking events, and call time, and ever since I’d hung up the phone after talking with the woman from the Veteran’s Crisis Line, I’d lost the energy and the desire to do any of it.

I finally had to admit that the story I’d been telling myself for a decade, that I’ll feel better when . . . was a lie. Winning an office had never made any of it any better, and being mayor would be no different.

I had no idea if I was even capable of getting better—if the damage was permanent—but at long last, I was ready to throw my entire self into finding out. I’d finally arrived at Rock Bottom, the international capital of having zero fucks left to give.

Two days later, I walked into the VA for the first time. I answered all the questions again. I met the psychiatrist who assumed I was hearing voices. The great creaking, lumbering machine of the VA began to turn its wheels. That was—I thought at the time—the easy part. Getting there had been the hardest thing I’d ever done. The next part was harder.

Adapted from INVISIBLE STORM: A Soldier’s Memoir of Politics and PTSD by Jason Kander. Copyright © 2022 by Jason Kander. From Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.