OUTSIDE BROWNING, Blackfeet Nation — On a warm morning in June, Brandon Boyce watched as a bison bull stepped away from its herd. The 16-year-old hunter, his face nearly covered in reddish-brown paint, fired, striking the bull behind the ear — a challenging shot, but one that kills instantly when well-executed and wastes almost no meat.

“Everything went right that day,” said Shane Little Bear, who helped prepare Boyce for the hunt. “He was blessed.”

Boyce’s hunting party loaded the massive animal onto the flatbed of their truck and drove it over Buffalo Spirit Hill Ranch’s rolling hills and into a field in front of a barn where a group had gathered, many of them standing beside coolers.

Several children ran up to the animal, oohing and aahing, while running their fingers through the thick tufts of fur around his neck. “His eyes are still open,” one said. “I want to help!” said another.

Five people of all ages and genders began to butcher the bison, first slicing and twisting the head from the spine, then cutting through the sternum with a jigsaw, thickening the air with the iron-laden smell of warm blood and fresh meat.

Termaine Edmo, a 35-year-old social worker who learned traditional butchery growing up in a family of ranchers, called out explanations to the crowd in a booming voice as the butchers worked their knives through the abdominal wall and diaphragm, then yanked the esophagus down the length of the bison’s body to hoist out the guts.

The tribe historically prized organs, especially the heart and liver, Edmo said, as a man walked around the crowd offering fresh slices of raw kidney. Under no circumstances, however, should they let bile spill onto the meat from the gallbladder.

Edmo passed off the stomach and intestines to a group of young girls, her daughters among them, who went to work emptying them. They searched the half-digested grasses and herbs in the stomach for invasive species, and dragged their fingers down the length of the intestine to squish out the excrement.

After the gutting, a rotating group of at least a dozen people broke down the bull into hulking chunks, calling out the cuts as they went to see who wanted to take them home, serving elders first: “Who wants flank? Rib meat? Leg roast?”

A generation ago, this scene would have been hard to imagine. Two centuries of pillaging by European settlers left bison nearly extinct by the 1880s. Private ranches fenced in almost all the survivors, transforming the buffalo from America’s most iconic wild ungulate into an afterthought for the livestock industry.

The Blackfeet Nation has spent more than a decade trying to change that, spearheading one of the most successful efforts to free wild buffalo back on their historical lands. Now, the hunt and collective butchering mark the climax of Iinnii Days, a three-day festival celebrating all things “iinnii,” the Blackfoot term for the animal known in English as “bison” or “buffalo.”

The celebration draws people from the four tribes of the Blackfoot Confederacy, as well non-Indigenous conservationists and curious tourists who straggle in from nearby Glacier National Park in northwest Montana. It’s the rare place a visitor might help build a medicine wheel, attend workshops on the benefits of regenerative grazing, and try their hand at fleshing the meat scraps and subcutaneous fat off of a fresh bison hide.

And perhaps most important, this year the festival acted as the rallying cry for one of the most unique conservation efforts in recent years.

On June 24, three weeks after Iinnii Days, the Blackfeet tribe took the historic step of freeing four dozen of the wild bison from Buffalo Spirit Hills Ranch onto a stretch of tribal land that borders Glacier National Park. The move sets the stage for the first large-scale, free-ranging bison restoration in decades.

It’s hard to overstate how much of an accomplishment that is. The bison may be America’s national mammal, but it’s also one of the country’s biggest conservation failures.

Somewhere between 30 million and 60 million wild buffalo roamed across North America at the dawn of the colonial era. Today, fewer than 450,000 bison remain, with livestock accounting for the vast majority.

Only about 20,000 wild buffalo are left in a smattering of conservation herds ― fewer than a tenth of a percent of even the most low-balled estimate of their historic numbers. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is currently reviewing whether the wild herd at Yellowstone ― by far the largest in North America, at about 5,000 animals ― merits federal protection under the Endangered Species Act.

And unlike other wildlife, only a tiny fraction of wild bison freely roam the landscape. Not even the grizzly bear, a 500-pound carnivore, faces such strict policing of its movements.

Buffalo find themselves in this unusual position for two main reasons, one biological and the other political. Being large and migratory, they need big stretches of land. Human settlement and agriculture, however, have swallowed up or fragmented the animals’ best habitat.

“Those buffalo were at the center of how a people viewed themselves. That being was everything. So what happens to a people or a person when that ‘everything’ is gone?”

– Cristina Mormorunni, founder of Indigenous Led

The political problem is that ranchers use most of the best remaining bison habitat to graze cattle — and most ranchers don’t want their cattle anywhere near wild bison. Not only do the two species compete for the same forage, but wild buffalo have a bad reputation for brucellosis infection.

Brucellosis is a bacterial disease that causes weight loss and spontaneous abortion. Outbreaks can devastate ranchers’ bottom lines and jeopardize their entire state’s access to export markets for beef. The U.S. Department of Agriculture has spent billions over the last three decades to rid the livestock industry of the disease, and for the most part has succeeded. But herds of elk and bison in the Yellowstone area, contaminated long ago by livestock, still carry the disease and threaten to spread it to cattle anywhere they might mix.

The result is that most of the few remaining wild buffalo in North America live behind fences.

Critics view this caging of bison as a double standard that doesn’t apply to elk, which is true. Many insist that bison can’t even infect cattle with brucellosis, which is false. But double standard or not, where ranchers hold political sway, proposals to let buffalo run free inevitably butt against opposition.

Conservationists dating back to Theodore Roosevelt have lamented the loss of America’s wild bison herds. Ecologists view them as a keystone species, whose selective grazing and wallowing maximized biodiversity and shielded grasslands from eroding into dust bowls.

But few have suffered the loss of wild bison more acutely than Plains tribes of bison hunters like the Blackfeet. Before European colonization, buffalo provided the Blackfeet’s most plentiful source of meat and most reliable source of fat — a precious nutrient for nomadic hunter-gatherers.

The animal’s hides covered their bodies as clothes and their lodges as roofs. They made cups from the horns, bags from the sun-dried bladders, and bowstrings out of the sinew. As the animals roamed from their summer range in high country basins to their winter range on the plains, the tribe followed.

That transcendent role meant the Blackfeet lost more than food and tools when white settlers nearly annihilated the bison, partly as a military strategy to conquer the Plains tribes that depended on them. The foundation stories, rites of passage, sights, smells and rhythms of life built around the perpetual chase after buffalo all added up to an identity that suddenly lived in a vacuum.

“Those buffalo were at the center of how a people viewed themselves,” said Cristina Mormorunni, founder of Indigenous Led, a key supporter of the restoration. “That being was everything. So what happens to a people or a person when that ‘everything’ is gone?”

That bleak situation has changed radically over the last decade, as bison returned to Blackfoot life, sometimes in novel ways. With more hunting opportunities both on and off the reservation, far more people have buffalo meat in their freezers. Some ranchers are swapping their cattle for buffalo, looking to harness the ecological benefits of an animal with whom they share a much longer history. Teenagers like Boyce barely remember a time without bison.

That shift has created a unique movement combining social justice, wildlife conservation and the assertion of cultural rights and traditional knowledge that is now beginning to reshape the larger landscape.

“This is basically the same thing as healing generational trauma,” Boyce said. “The buffalo is a part of our community again. It’s just awesome. You drive out of Browning and you see buffalo next to the road. It’s just a beautiful sight to see.”

A Decadeslong Return

A thick-framed man with a soft-spoken demeanor, Ervin Carlson brushes off credit for the Blackfoot buffalo restoration. When asked, he says the animals themselves made them do it. Few people, however, have worked on the issue longer or more effectively.

The Blackfeet first started bringing buffalo back to tribal land some time in the 1970s, Carlson said. The animals weren’t popular. The tribe managed them as livestock, but struggled to control them. They busted easily through fences, angering landowners who had to chase them off. Contractors managed them at first, followed by the Fish and Wildlife Department.

“There was a lot of controversy, even from our own people,” Carlson said. “Buffalo had been gone so long, people weren’t used to them.”

In 1996, the Blackfeet Tribal Business Council handed off the unruly animals to Carlson. The same year, they appointed him as the Blackfoot representative to the Inter-Tribal Buffalo Council, an organization dedicated to restoring buffalo to tribal lands across the country.

Back then, Carlson served as the tribe’s agricultural director, charged with building its cattle herds. He knew pretty much nothing about bison. But the years of hands-on experience and exposure to the ITBC’s mission-driven work fueled a passion for the animals and a desire to see them back on the landscape not as livestock, but as wildlife.

He found a partner in Keith Aune, a fellow buffalo enthusiast then working for the Wildlife Conservation Society, a well-funded nonprofit. By the time the two met a little more than a decade ago, WCS had already mapped out some of the most favorable areas in the United States to restore wild bison.

Glacier National Park — which borders the Blackfeet Nation and is part of the tribe’s historic homeland — emerged as one of the most obvious choices. With more than 1 million acres, it offered a lot of space and quality bison habitat. Canada’s Waterton Lakes National Park to the north tacked on another 125,000 acres.

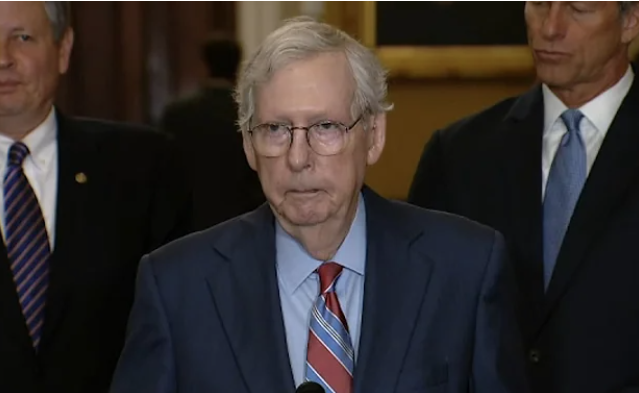

The Washington Post via Getty Images

Both parks have long supported the idea, but cumbersome federal regulations and the contentiousness of bison politics in Montana made the National Park Service unlikely to lead the charge.

Tribal governments, on the other hand, face fewer restrictions. Though composed of U.S. citizens, federally recognized reservations have a hybrid form of government somewhere between a state and a nation. Tribal sovereignty dictates that if they want to release wild bison onto their own land, neither the federal government nor the state of Montana can stop them.

By that time, Carlson had spent years nurturing the dream of bringing wild bison back, while wondering whether the tribe really wanted them. When he and Aune approached the tribe’s elders with the idea, they found wholehearted support. But it came with a condition — they would have to get the whole community involved, especially the youth.

The reason behind that request was that a successful buffalo restoration revolved around more than the animal. Colonialism severed some of the most cherished ties to the past for many Blackfeet.

Archeologists and thieves made off with countless families’ bundles, ceremonial objects passed down by inheritance. As with other tribes, the federal government stripped generations of Blackfeet children from their families and forced them into boarding schools, where they were punished for speaking their native language and forbidden from dressing how they would at home.

Bison restoration, tribal leaders hoped, could bridge the chasm separating the youth from the “old ways” that many lost touch with over the century-long federal policy of forced assimilation.

“In an effort to reclaim what was taken, I think a huge piece of the story is that spiritual connection to the buffalo,” said Kim Paul, the executive director of the Piikani Lodge Health Institute, an Indigenous-led nonprofit that supports the bison restoration as part of its mission to promote well-being in Blackfeet country. “It’s really our umbilical cord to knowing that our children and generations are going to continue. If we can figure out how to turn around all the assimilation efforts that happened, the buffalo is key.”

More than 100 community meetings across the Blackfoot Confederacy followed for what came to be called the “Iinnii Initiative.” Cattle ranchers shared their worries. The organizers held public feasts. They worked with students and professors at community colleges and universities. Resistance softened and enthusiasm grew.

“It became real,” Carlson said. “They realized how important these animals were to us. It changed everything.”

‘We’re Really Doing This, Aren’t We?’

Many here refer to the restoration as “bringing the buffalo home.” It’s not just a metaphor.

In 2016, the Blackfeet Nation received 87 wild buffalo calves from the Canadian government, in a transfer funded by the Wildlife Conservation Society. (The state of Montana objected to sending adult bison, Carlson said.)

As wild bison neared extinction in the 1870s, a man by the name of Whist a Sinchilape, or Samuel Walking Coyote, trapped four bison calves and later sold them to Michel Pablo and Charles Allard. The two ranchers, both of mixed indigenous-European heritage, used the animals to help build up a conservation herd over the following decades, letting them range freely across the lands of the Flathead Reservation in northwest Montana. By the turn of the century, the Pablo-Allard herd numbered more than 700, making it North America’s largest.

Congress destroyed their accomplishment with the Dawes Act. Passed in 1887, the legislation broke up tribal holdings, allotting parcels out to individuals and families, in an attempt to transform cultures of semi-nomadic hunters into farmers and ranchers.

The Bitterroot Salish, Upper Pend d’Oreille, and the Kootenai Tribes refused to give up their lands until 1904, when President Theodore Roosevelt forced them to by signing the Flathead Allotment Act into law.

Allotment broke apart the tribal land the Pablo-Allard herd had roamed. They tried to sell the herd to the federal government, but couldn’t agree on a price. In 1907, the Canadian government bought the herd, settling them in what is today Elk Island National Park in Alberta.

“This is basically the same thing as healing generational trauma. The buffalo is a part of our community again. It’s just awesome.”

– Brandon Boyce

The Dawes Act remains the single greatest obstacle facing any tribe working to restore wild bison herds to their land. The Blackfeet Nation’s unique advantage was that a jagged strip of tribal land running along the eastern edge of Glacier National Park was reserved from allotment, making it analogous to federal public land.

Still, finding a spot to turn out buffalo remained a challenge for years. Several cattle leases remained active on the ideal choice, a patch of land next to towering Chief Mountain, a spiritual landmark for the tribe.

The breakthrough moment came during the pandemic, according to Blackfeet Tribal Business Council Member Lauren Munroe Jr. Under the economic strain, some ranchers could no longer afford their leases. Conservation groups stepped in to buy out others. After three years of rest, the Blackfeet business council voted unanimously to begin releasing wild bison there.

“I got butterflies,” Munroe Jr. said. “It was like, ‘Oh my god, we’re really doing this, aren’t we?’”

‘There Was A Time When We Didn’t Have Buffalo’

If youth engagement is the standard, then the restoration has become a runaway success. Children of all ages ran across the grounds of Buffalo Spirit Hills Ranch on the second day of Iinnii Days this year. Some wore buffalo masks made from white paper. Others designed leather bags from a tanned bison hide.

In the afternoon, Latrice Tatsey divided some of those youngsters into groups of “iinnii” and “hunters” to reenact a buffalo jump, a traditional method of hunting by setting bison stampeding over a cliff.

The iinnii group lined up single file inside a ring of birch trees that acted as the festival’s main gathering point. Above their heads, they stretched a buffalo hide. At Latrice’s command, they sprinted off, followed by the hunters, with one young man struggling to stay mounted on top of a speeding pony as they chased the iinnii past three towering tipis and off toward the hills.

“Tomorrow we’ll have a modern hunt with a gun, but this is how our ancestors did it,” Tatsey called after them. “There was a time when we didn’t have buffalo, and our people were pitiful!”

The youth’s exposure to buffalo now stretches beyond the annual festival. Edmo, who announced the butchering session, leads outdoor butchery classes two or three times a month, spearheading a movement to use traditional animal harvest as a climate-change-fighting method to enrich soil.

“You’re seeing more interest in the youth,” Edmo said. “Every time I do a harvest and have a school there, I could have 100 to 200 kids. Their eyes are wide and they want to touch everything.”

It’s possible that one day in the future, some of them will have the opportunity to hunt wild bison on tribal land once again — though for now, the herd remains too small to support more than occasional hunts.

In the meantime, the buffalo continues to permeate all aspects of Blackfoot society.

Unlike cattle, buffalo co-evolved with Montana’s grasslands. Historically, they tended to congregate over a patch of land and graze it down to stubble, then move on, letting it rest for years. That pattern appears to send roots deeper, helping them sequester more carbon, enrich soils and foster biodiversity. Regenerative ranchers like Tatsey, who is also a soil scienti try to emulate that pattern by rotating their animals across a series of paddocks for shorter periods of more intense feeding.

“We understand bison aren’t going to be able to fully be on the landscape like they historically were,” Tatsey said. “If I can’t get bison everywhere, how can I get their practices back on the land, so those ecological relationships are restored?”

The tribe maintains a growing commercial herd, whose meat finds its way to both local grocery stores and restaurants serving visitors to Glacier National Park.

The Fish and Game office issues a limited number of tags for individuals to harvest them, but for most Blackfeet, hunting outside Yellowstone National Park, where the state of Montana honors historic treaty rights to hunt off tribal land, remains the most reliable way of filling the freezer.

But in the near future, hunting wild buffalo on tribal land at the foot of Chief Mountain will again become possible.

“I’m really glad that they show all the younger generations how to do it,” said Boyce, the young hunter. “If the younger generation doesn’t know how, there’s no future.”

![Family Feud Contestant Murdered His Wife, Will Spend Life in Prison [VIDEO] – TVLine Family Feud Contestant Murdered His Wife, Will Spend Life in Prison [VIDEO] – TVLine](https://washingtonweeklytimes.com/wp-content/themes/jnews/assets/img/jeg-empty.png)