My approach to Black history is spiritual. I want to know how my ancestors loved themselves and each other — acts of resistance in a world that tried to erase them — so I can move through the world as my most authentic self. I want to know all of it, not just the history that has been given to me growing up in school, but the parts that have been intentionally left out.

Thinking back to history class, I feel like pieces were missing. Even back then, I longed for nuanced stories of Black historical figures. Many of the voids left by my teachers, however, were filled in by my parents and grandparents, the latter of whom lived through Jim Crow and the Civil Rights eras. And I did fortunately get to explore some fiction that provided a much-needed glimpse into the Black gender and sexuality spectrum.

In seventh grade English class, Alice Walker’s “The Color Purple” offered me a window into the lives of Black women who experienced all the hardships of racism in the antebellum South and still cussed, sang, threatened their husbands, and sometimes kissed other women. As a preteen, Walker’s literary prose provided me a more complex representation of Blackness, but witnessing her more recent transphobic comments has only made me more aware of how our understanding of self is sometimes informed by inadequate and violent historical texts and beliefs.

“The Color Purple” made me realize that Black history is so much more than the under-developed characters I was often taught about in school, their stories flattened, and pieces of their identities blotted out to fit a palatable narrative.

There are many of us out there, still thirsting for more honest stories about Black life, love, joy and struggle. Two out of three Americans believe the Black history education lessons they received fell short. I have recently started doing my own research and following content creators such as Erika Hart, who devote their entire platforms to honoring Queer Blackness in the past and present.

Over the past year in particular, conservative politicians and education officials such as Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis have continued to wage war against critical race theory. Unsurprisingly, much emphasis is placed on removing queer Black history, replacing it with topics like “Black conservatism.” These actions are reflections of the lengths conservatives will go to continue to strip African descendants of the potential to move forward culturally, socially and spiritually. At this point, we should all see it as a tactic to keep us divided.

The persisting belief that gender is a binary construct doesn’t just create distance in our communities, but it also contradicts important parts of our history. The gender binary was a concept that many of our African ancestors did not conform to pre-colonialism; many informed experts argue that the binary is far more closely aligned with eurocentric views of gender expression.

Amber J. Phillips, known as Amber Abundance on social media, is a queer storyteller who has written poignant pieces about the hidden queer identities of Black culture-makers and leaders. “My biggest fear when I came out was that it would separate me from my family. And our families connect us to our Blackness,” she said.

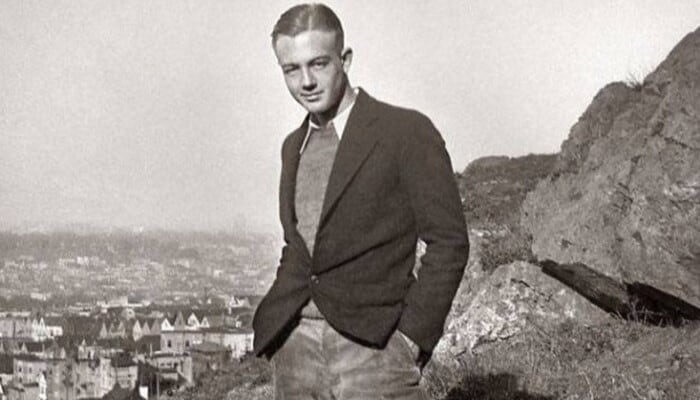

Phillips, raised in Columbus, Ohio, remembers growing up with a deep appreciation for Blackness and Black culture but also experiencing “hushed tones” around the gender identities of some of the most iconic Black figures. “I remember being ― at my big, grown age ― in college and hearing for the first time that Langston Hughes was gay. And I was like, ‘What are you talking about?’” said Phillips.

She also noticed how this covertness played out in her own life. If there were rumors of you being queer, you were kept out of certain social settings and people felt no hesitation in distancing themselves from you.

According to Phillips, this mindset is part of the violence of erasure, which is common even within Black social circles and institutions. During 2022’s BET awards, she noted that Jack Harlow was nominated for an award and Lil Nas X wasn’t — he reportedly wasn’t even invited to the show.

“People will make that about race, and they definitely should. But when we look at the archives, they have intentionally erased one of the biggest pop stars of our time,” Phillips said, citing homophobia in the community. “When we start talking about Black Trans people, and we’re like, ‘Well, back in my day, we didn’t have none of that.’ Actually, you did.”

Let’s be real: We collectively fail by telling Black history that’s not nearly queer enough.

In order to understand both the intricacy of her identity and historical queer erasure in Black history better, Phillips dove even deeper into research. During her work, she found evidence of LGBTQ+ leaders fueling several prominent liberation movements in America. It’s not just James Baldwin, Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen in literature, and Bayard Ruston and Marsha P. Johnson as organizers, but countless others who fought for all of our rights. Phillips believes that acknowledging the gender identity and sexual expression of these individuals is essential, not just out of respect for them, but to eliminate the shame the Black community has around queerness.

“If we can honor Black queer people, we could learn how to be better to each other. We could find more systems of community care and mutual aid,” she said. “We could free people from internalized anti-Blackness. There are answers, and some of them exist in the minds and the work ethic of Black queer people.”

Watufani Poe is an interdisciplinary social scientist and educator who is among the scholars looking to shift the conversation to include the historical contributions of individuals who do not conform to the gender binary. Poe’s upbringing in a pan-Africanist home exposed him to the limitations of existing Black history teachings ― teachings, he says, that introduce children to positive images of Blackness but often pass on heteronormative gender constructs.

“There’s a kind of push to recuperate a unified image of what Afrocentricity is,” he said. “I understand the strategic use for that … and I’m fine with that as a first step, but that’s not the last step.” In other words — and I agree — we have a lot more work to do.

While working as a postdoctoral fellow at Amherst College, he co-created a course called “Black, Here and Now,” that walked students through the historical struggles and contributions of Black queer communities throughout the diaspora. For his syllabus, he pulled from the works of queer thinkers, scholars and storytellers documented between the late ’60s, ’70s and ’80s to introduce students to the historical presence of Black queer people in culture and movements.

Poe mentioned how challenging it was to access primary and secondary sources before the ’60s, not just because of censorship of Black stories but also because of the eurocentric, heteronormative manner in which Black life was documented — especially during the transatlantic slave trade and chattel slavery. “We’re dealing with documents about the business of the slave trade … How many bodies arrived, how many people died on the journey?” he said. This is just one way enslaved Black people were forced into a gender binary with no regard for the various cultural identities they were being stripped of.

In other instances, however, queerness shows up boldly. In the Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking Americas, Poe says there’s a good amount of evidence in the form of inquisition documents and of people who don’t follow heteronormative rules. Because these documents are essentially notes by overseers reporting “sins and the ways in which they sinned,” Poe suggests being mindful when referencing them because they carry the violence of colonialism.

Poe marvels in our ability to reclaim stories of our humanity, as well as preserve and protect those of our ancestors. “The fact that we even have copies of ‘Their Eyes Were Watching God’ readily available today is because Alice Walker did the work of recuperating the works and the image of Zora New Hurston,” he said. “And in Brazil, I find that Afro-Brazilian religious traditions are rich archival spaces to pass down the histories of the Black communities there.”

As I continue my journey, I’m starting to gather that Black queer history does exist — we just need to actively seek out these stories in order to release the shame around queerness and gender fluidity. This will allow us to completely let go of narratives that dehumanize anyone who doesn’t fit heteronormative or eurocentric standards.

“It’s not about finding myself in the archive or finding this Black Queer or Trans person that we see today,” Poe said. “Seeing the complexity of Black people, the complexity of human nature, I think, [is] the most important thing to take away.”