The perfect version of the metaverse, to hear tech heads like Mark Zuckerberg tell it, marries social media, entertainment, and—most exciting of all—meetings in one pristine virtual space. Long ago foretold in Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash, it is a place where the online world offers more experiences than the flesh-and-bone one. But whereas Stephenson’s metaverse was part of an apocalyptic future, modern inventors have promised a digital utopia.

Unfortunately, the metaverse they’ve built has, so far, lived up to those expectations about as well as a Craigslist apartment rented based on photos alone. Zuckerberg’s Horizon Worlds, clunky and strange, may have been at its most thrilling when Meta informed users that legs for their avatars were “coming soon.” The hardware needed to visit such virtual worlds—often a headset like Meta’s Quest Pro—can be pricey and cumbersome, and once you get there, it’s no party.

None of this is lost on those who actually build digital worlds. In a survey released today by the organizers of the Game Developers Conference, a whopping 45 percent of them said “the metaverse concept will never deliver on its promise.” It was the most popular response to a question about which companies or platforms are “best placed to deliver on the promise of the metaverse concept,” and a telling sign of what kind of faith the industry is putting in the long-term potential of immersive virtual worlds. “The people trying to sell it have no idea what it is,” wrote one respondent, “and neither do the consumers.”

The survey, released by GDC ahead of its annual event in late March, comes after a rough 2022 for metaverse evangelists. Not only is there cynicism about who is building these worlds, and for what purpose, but many potential metaverse inhabitants aren’t convinced there’s any there there. Meta lost money and laid off workers last year, and even proto-metaverse worlds like Minecraft and Roblox now sit low on the game developers’ list for anticipated success.

It’s not for a lack of trying. Some developers are still interested in releasing AR/VR games on platforms like Meta Quest and PlayStation VR2. Of those polled, 36 percent listed Meta Quest as a platform they expect to release their next game on. For PS VR2, that number is 18 percent.

Faith in the metaverse, as the survey put it, lies with Epic Games. While nearly half of respondents said its promise will never be fulfilled, 14 percent did think that if any platform had a shot at doing so it was the company’s Fortnite. Meanwhile, only 7 percent thought Horizon Worlds had a shot; same with Minecraft. Five percent thought Roblox could do it.

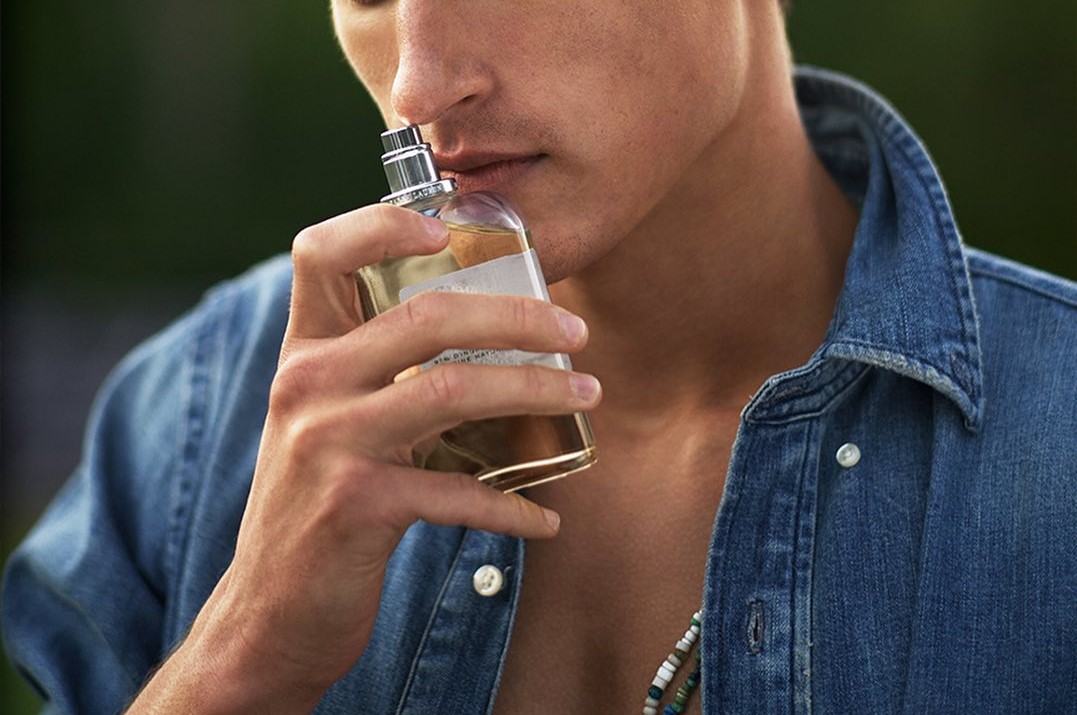

Fortnite earned that confidence over the years thanks to Epic’s curation of events like in-world concerts featuring artists such as Marshmello, Travis Scott, and Ariana Grande. No longer just a place for players to duke it out, it’s a space where people can enjoy other forms of entertainment together. But Fornite was not the first game to offer virtual communities, nor even the second or third. “The metaverse needs to acknowledge that it is reinventing the wheel,” one respondent said, pointing to Linden Lab’s 20-year-old virtual world, Second Life. “And then identify why people lost interest in the wheel the first few times around.”

“[The metaverse] already exists and is sustainable,” another developer wrote. “It’s simply being re-sold as a new concept by corporations trying to profit off it.” (In Meta’s case, its pivot to the ’verse has been accompanied by plummeting profits and flat growth.)

The metaverse may one day see its true potential realized, but it likely won’t be as Zuckerberg, or even Stephenson, imagined it. For the metaverse to become a true alternate reality, it needs to be built by its own users. “Any version of it that exists solely in the hands of one corporation as an ad platform, virtual workstation, or virtual real estate market is doomed to fail eventually,” one developer wrote. “It needs to be built of things users actually care about.”

![Mandy Patinkin as [Spoiler], What’s Next for Oliver and Josh in Season 2 (Exclusive) Mandy Patinkin as [Spoiler], What’s Next for Oliver and Josh in Season 2 (Exclusive)](https://www.tvinsider.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/brilliant-minds-113-oliver-mandy-patinkin-1014x570.jpg)