When it comes to antitrust and tech, there’s a trust deficit on Capitol Hill, even as pressure to act continues to mount. And Senate Democrats trust Speaker McCarthy to do one thing: protect American-made monopolies.

“I think the sentiment is there, but we’ve had a difficult time getting Republicans to support legislation in this area,” says Senator Brian Schatz of Hawaii, a Democrat.

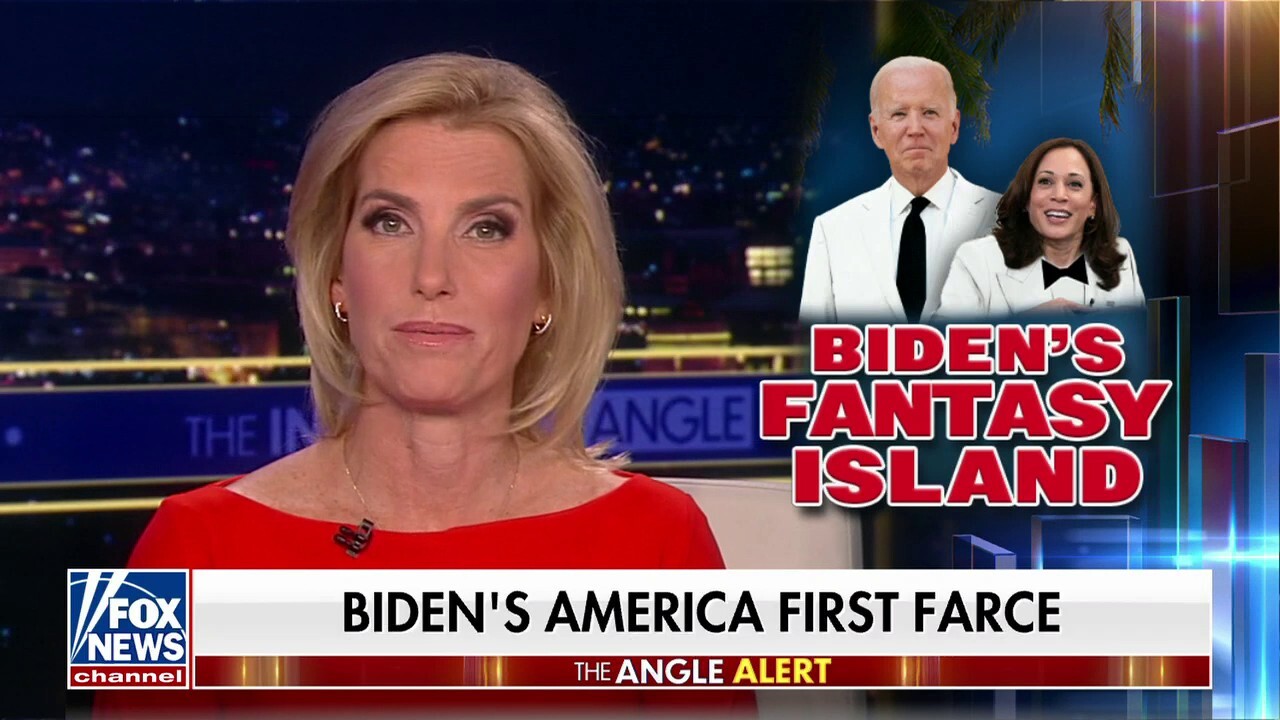

House Republicans may see common ground with Biden’s new tough-on-tech approach, but this is no kumbaya Congress—and the rest of Biden’s State of the Union vision, on first blush at least, has been portrayed by Republicans as a laundry list of reasons to never work with Biden, no matter their common tech foes. “What we saw tonight was Joe Biden talk about unity in one breath followed up with bashing and rolling Republicans,” says Republican congresswoman Kat Cammack of Florida. “That, to me, just shows he’s not serious about getting things done for the good of the American people.”

After dismissing the bulk of the president’s agenda, Cammack admits there was one bright spot. She calls Biden’s stern message to Silicon Valley “encouraging.”

“We have a really serious problem when it comes to our personal data being collected without warrants, being sold without our permission, and it’s time that we put people’s data and privacy back in their hands,” Cammack said. “So I was encouraged to hear that, but it’s a long road between now and then.”

Long road ahead, surely, but House members are only granted short, two-year windows of service, and the sprint to 2024 is already on. Pomp and circumstance was last night’s dress code, even if some got a different memo. But now the focus moves to legislating—and, especially on the eve of a presidential election, that means bomb-throwing and finger-pointing.

Democrats and Republicans alike have failed to put up guard rails on the Silicon Valley donor class in recent years, even as both parties continue decrying the very tech sector Washington policymakers have refused to regulate, all while Americans’ data is mined, shared with law enforcement, or sold to other third parties. Hot air and deflated rhetoric aren’t options for this 118th Congress, according to Cammack.

“Truth be told, I don’t think we have a choice,” Cammack says.

“We have a divided Congress, and Republicans in the House are serious about data protection for consumers, for Americans, and I think Democrats are as well. The trick is going to be putting a bill together that not just survives Congress but will avoid a veto when it gets to his desk. So that’s going to be where the rubber meets the road.”

Tech politics are different than other hot-button issues. They’re at once bipartisan—everyone has a gripe or three with Big Tech—but they’re also stubbornly stuck in Washington’s rigid partisan patterns. That’s why soaring rhetoric only goes so far, even as the mistrust is seemingly endless. Hence, the details are often the devil.

“These are tough conversations. We all value privacy. We all want to protect our children,” says Senator Kevin Cramer of North Dakota, speaking for many of his fellow Republicans. “But we also like free enterprise. We like innovation. I always think it’s better to knock down barriers to competitors than it is to regulate the incumbents, so to speak, in business.”

Senators tend to be a little older than their House counterparts (according to Pew Research, 7.4 years older, on average). In recent years, the chamber’s octogenarians proved themselves the butt of Silicon Valley jokes, but times are changing—at Senate speed.

All five of the Republicans who captured Senate seats in November are bullish on Big Tech. While it’s unclear how quick—or successful—they’ll be in their efforts to educate their anti-regulation Republican elders, Silicon Valley’s congressional critics say Biden was wise to focus on protecting children’s private data. It’s a message that resonates far and wide, even on Speaker McCarthy’s Capitol Hill.

“But this issue of targeting our children with certain messages, using technology to basically gather data and persuade or take advantage of their habits, it’s really quite unnerving in this modern era,” Cramer says. “I think a lot of us traditionalists have to struggle a little bit with our basic individualism, with some protection.”