The slowdown was inevitable, of course. Nothing stays hot forever — especially in this industry. By tech standards, smartphones have had a good run, but the last few years have seen device makers searching for the magic bullet to help the sales slide reverse course. The arrival of 5G was a nice reprieve, but next-generation telecom standards don’t arrive every year.

It’s too early to say with certainly whether the move toward device repairability in the midst of new and proposed legislation will have a meaningful impact, but it was a highlight at this year’s show, which HMD turned into a central thesis. Regardless of how many people take advantage of the ability to repair their devices at home (or have a third party repair them), it’s another potential pain point for industry growth.

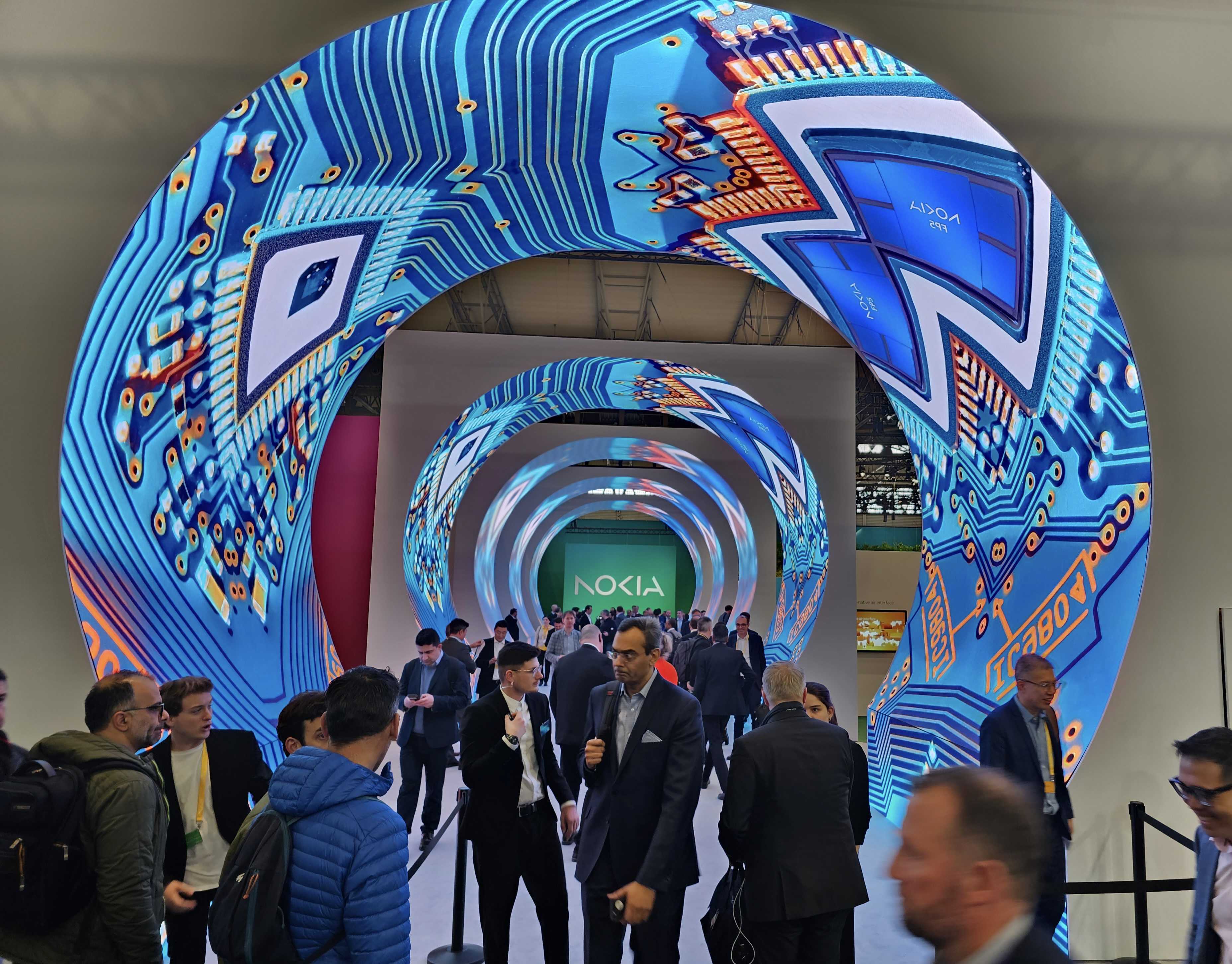

Nokia booth at MWC 2023. Image Credits: Brian Heater

Foldables have seemingly performed many expectations (specifically for Samsung), but not nearly enough to really move the needle. Phone makers have a refresh problem. For a long time, phone purchases were inexorably tied to carrier plans, putting the devices on a two- or three-year cycle. Of course, the kinds of financing deals that let you spend less up front have a way of making you pay in the end.

There does seem to be a looming sense of carriers and manufacturers attempting to return to something similar with a new name.

“I think there’s going to be more of a movement toward models where devices themselves are sold more as a service,” Google’s Sameer Samat told me this week. “I think there’s a lot of innovative work going on in the carrier side to figure out how you buy a device for less up front, you use it and return it after a period of time and you get another device as part of your overall subscription.”

Image Credits: Brian Heater

In a world where we don’t own our movies, music or software, the concept of “hardware as a service” is rapidly emerging as its own path forward. Like the move from physical albums to Spotify, it has trade-offs.

Some consumers will no doubt jump at the opportunity to upgrade hardware without a thought, but is not owning your phone the same as not owning a CD or record? Will these ultimately end up costing us a lot more in the end? And in a time when most manufacturers are touting percentages of recycled materials, how much more waste will this model create?

There’s also a sense phone makers effectively painted themselves into a corner. The yearly one-upmanship ultimately benefited consumers with much better devices. I’ve said this a bunch, but these days it’s hard to find a bad phone for more than $500 — there are also an increasing number of good ones for less than that. These days, a “budget” device often involves settling for last year’s best chipset.

Better phones last longer, both in terms of durability and futureproofing feature set. Having a three- or four-year-old phone these days doesn’t mean the same thing it meant three or four years ago. That’s also due, in part, to the fact that innovation has slowed. It’s become a battle for inches. When was the last time you saw a truly revolutionary upgrade from last year’s model? Do moderately better screens, cameras or even batteries compel that many people toward impulse purchases?

“The smartphone market grew initially because there was a really innovative product that was useful to customers,” Nothing’s Carl Pei told me in an interview this week. “Now it’s starting to shrink, because my phone is good enough. Why should I upgrade?”

Image Credits: Natasha Lomas/TechCrunch

Taking the broader view, none of this is bad, per se. It means better products for consumers, as well as a slowing of the massive waste generated by millions of people buying a new device every other year. We all tacitly understand why corporations and shareholders hope such cycles will sustain forever, but many of us are glad they don’t. Companies need one of two things to happen: either reversing the slide or shifting focus to other revenue streams.

“There will always be sales of new phones,” says Samat. “But I think you’re now reaching the point where this is, for many people, it is their primary computing device. So, there are different and more interesting ways of looking at the market. I think in terms of what are you able to do with these devices? What does engagement look like? What are the services that you’re utilizing? And how is it integrated with other parts of your life?”

The writing has been on the wall for a while. The slowdown pre-dates the pandemic by some time, but the last three years have certainly accelerated the trend. Shutdowns, unemployment, inflation, supply chain constraints — you know the deal. Forward thinking companies invested heavily in content plays. That’s certainly paid off for Apple and some of the competition, as well. There were moments where wearables and smart home devices seemed like they might help stem the bleeding, but while both have done well for manufacturers, there isn’t the same sense of ubiquity.

6G isn’t anything beyond a number of different companies vying for adoption of their specific solution, so we’re looking at years before the first devices start arriving. At a conference that loves nothing more than hyping a new technology, 5G’s potential replacement only warranted a single panel.

Mike, who sat in on the panel, notes:

The first thing to note is that it’s not arriving anytime soon. The projections are that the likes of you and I will only get 6G into our hot little hands from around 2030 onwards, so it would be best to quell your ire for now.

Anyone else feel like it’s 50/50 between 6G and Mad Max scenario for 2030? Okay, maybe it’s just me. Even so, that feels impossibly far away and doesn’t do much for any of these companies in the near term.

Oppo’s Find N2 Flip at MWC 2023. Image Credits: Brian Heater

Maybe foldables have a lot more juice left in them? If MWC was any indication, manufacturers certainly believe so. It seemed like every company had one this year. Well, everyone except Nothing.

“I personally think foldables are supply chain-driven innovation and not consumer insights,” Pei said. “Somebody invents OLED, and they can make a lot of money, because it’s a great technology. Then after a few years, a lot more companies make that, so they need to lower their prices. So they need to figure out what else they can sell at a higher margin. They develop flexible OLEDs, which they can sell at a higher price.”

Image Credits: Brian Heater

It’s hard not to be cynical about this stuff sometimes. Ditto for concept devices, though as I noted in my “ode to weird tech” post, as someone who follows this stuff for a living, I’m a fan of weirdness for weirdness sake, be it the rollable Motorola Rizr screen or the OnePlus glowing cooling fluid. Certainly following the automotive industry’s lead of creating concept devices is a trend that is likely to only become more pervasive.

OnePlus COO Kinder Liu told me this week that gauging consumer interest is one of the “multiple reasons” his company is engaging with the concept. He added, “Also, we want to encourage continuous innovation inside our company.”

Pretty much everyone I engaged with this week echoed the sentiment that smartphones are in a rut. For the first time, however, it’s not a foregone conclusion that there’s a way of getting out.

![Outlander's [Spoiler] Dies In Brutal Episode 2 Attack — Read Recap Outlander's [Spoiler] Dies In Brutal Episode 2 Attack — Read Recap](https://www.tvline.com/img/gallery/outlanders-spoiler-dies-in-brutal-episode-2-attack-read-recap/l-intro-1773408115.jpg)