It’s been a monumental year for Crispr, the molecular tool scientists use to edit genetic material. This November, the United Kingdom authorized the first medical treatment using Crispr gene editing, giving people with sickle cell disease new opportunities to receive a one-time therapy to prevent episodes of terrible pain. This week, the US Food and Drug Administration is poised to make a decision about the therapy. What was once seen as a moonshot is already changing lives.

Right now, though, it’s still a rarefied treatment. “It’s expensive,” Jennifer Doudna, the pioneering biochemist who won a Nobel Prize in 2020 for her work on Crispr, told WIRED’s Emily Mullin at the LiveWIRED conference this week in San Francisco. The therapy is expected to be priced at over a million dollars a patient, which could make it inaccessible to many of the people who need it most.

It’s also a complicated process. Patients have stem cells taken from their bodies, edited in laboratory settings, and then put back in. Doudna is optimistic for a future where Crispr-based treatments are far less invasive than they are now. “Maybe even a pill at some point,” she says. “Today that sounds a little bit fantastical, but I think it’s very achievable.”

In 2014, Doudna founded the Innovative Genomics Institute to apply Crispr technology to health care questions. Doudna hopes that the IGI’s research can also help make these technologies more affordable and accessible; she’s also very interested in how Crispr might be used to fine-tune the microbiome.

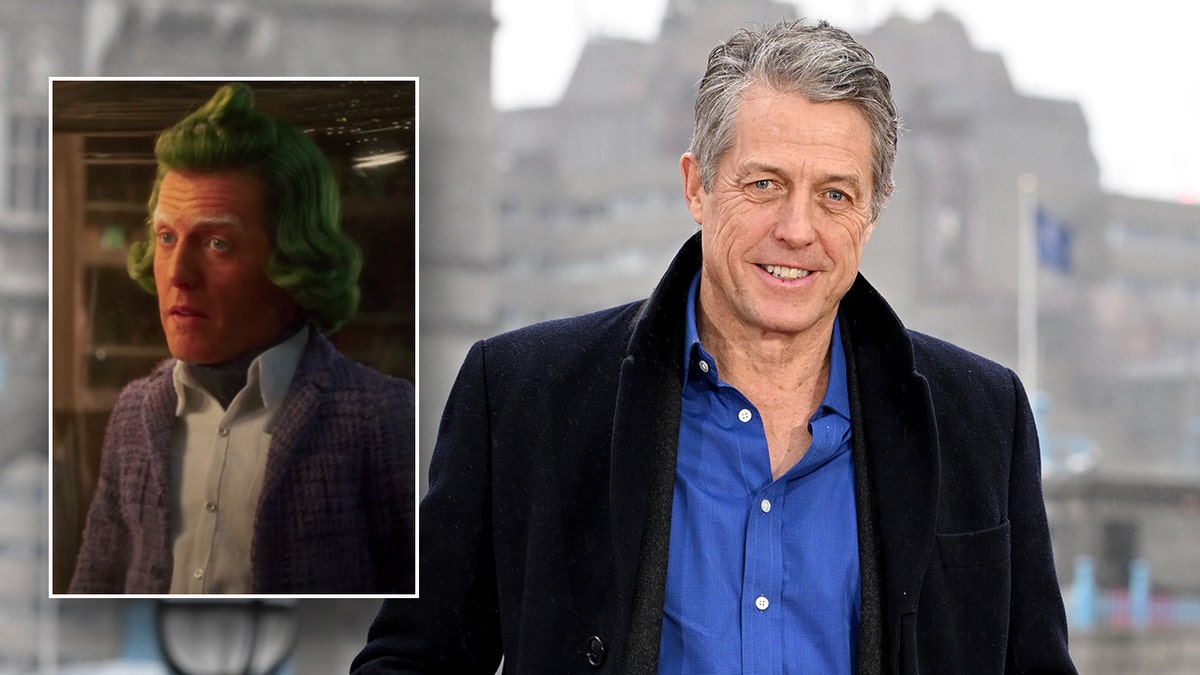

Emily Mullin, Staff Writer at WIRED, and Jennifer Doudna speak onstage during The New Age of Medicine at LiveWIRED 2023.Photograph: Kimberly White/Getty Images