In the months since Elon Musk took over, and subsequently tanked, Twitter, people have been desperate to find an alternative platform. Bluesky, a decentralized social network backed by Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey, is the latest frontrunner.

Bluesky has already gained attention with its irreverent posting culture, but to keep users, it needs to maintain a safe environment for sex workers and other marginalized communities.

In recent weeks, Bluesky has been hailed as a shitposting wonderland and a welcome respite from the increasingly rancid vibes that Twitter has been festering in since Musk took over as CEO. The user interface is nearly identical to Twitter’s. Instead of tweets, users widely refer to posts as “skeets” — despite protest from Bluesky CEO Jay Graber and others who don’t find slang for semen absolutely hilarious.

Reception to Bluesky has been overwhelmingly positive, with users comparing their feeds (unofficially known as the “skyline”) to “the first day of high school” and “early Twitter vibes.” One user described Bluesky as a much-need smoke break, skeeting, “this app is like the cousins you ‘go for a walk’ with at your conservative family’s thanksgiving dinner.”

Bluesky’s posting culture is noticeably less hostile than Twitter’s — for now.

Though discourse on Bluesky flares up every now and then — like whether users should be allowed to threaten generally disliked public figures with hammers — so far, conflict doesn’t usually reach the fervor of a Twitter spat. Since Bluesky is still invite-only, and users lose remaining invite codes if their invitees are banned, there’s a unique incentive to maintain a less toxic environment than on Twitter. Granted, Bluesky is still in its extremely early days, and with such a small user base, it hasn’t been around long enough for hostility to brew like it has on Twitter.

Bluesky, like Mastodon, aims to be a decentralized, federated social network. But instead of running on ActivityPub, the protocol powering Mastodon and other open source social platforms, Bluesky uses its own AT Protocol, and aims to establish a community labeling system that would allow users to “opt in” to certain content filters. The company also plans to allow users to choose what they want to see by offering a “marketplace of algorithms” instead of using a conventional “master algorithm” employed by most social media sites. Users will be able to switch between seeing specific feeds and viewing multi-algorithm feeds.

“Moderation is a necessary feature of social spaces. It’s how bad behavior gets constrained, norms get set, and disputes get resolved,” Graber wrote in a recent blog post. “We’ve kept the Bluesky app invite-only and are finishing moderation before the last pieces of open federation because we wanted to prioritize user safety from the start.”

Even in its bare-bones state — users can’t even send DMs yet — Bluesky’s culture already stands out among Twitter alternatives. Mastodon, for example, is populated by tech enthusiasts, academics, and journalists, but tends to be so dry that there’s little motivation to scroll it for fun. Skeets, on the other hand, lean into the unhinged. Nudity and sexuality aren’t censored, and scrolling past tiddies on the skyline is to be expected. The cheeky posting culture that exists on Bluesky has only encouraged non-Silicon Valley insiders to join, bringing a fresh energy that other Twitter would-be alternatives are sorely lacking.

Bluesky is a fetus among social media giants like Twitter and Facebook. But in its earliest stage, it has a unique opportunity to cultivate a diverse, vibrant community of the users who made Twitter fun. In its heyday, Twitter’s memes, mutual aid networks and other redeemable traits existed because of Black Twitter and sex workers. Much of internet culture originated in Black communities. “Not safe for work” (NSFW) Twitter receives consistent, and growing, engagement. Adult content makes up 13% of Twitter, according to internal documents obtained by Reuters last year.

Aveta, a Black software engineer who has invited over 500 Black users to Bluesky, wasn’t a fan of Mastodon because “a lot of Black people weren’t on there,” and “there was a lot of racism that was going unchecked.” She asked to only be referred to by her first name out of fear of harassment. She made it her mission to invite as many Black users as possible, she said, because Black communities drive the culture of social platforms like Twitter, Instagram and TikTok.

“It’s so crazy that despite how much time has passed, exposing how Black people have so much power and influence, especially in tech communities, especially in social media, that people want to disregard that,” Aveta said. “Yeah, there were people who were in before all that, but the ones who really got it jump started, who really came in at the middle, were Black people.”

Before Aveta started inviting other Black users to Bluesky, the site was “very white, very quiet and very small.” She said there was a noticeable vibe shift as more of Black Twitter joined.

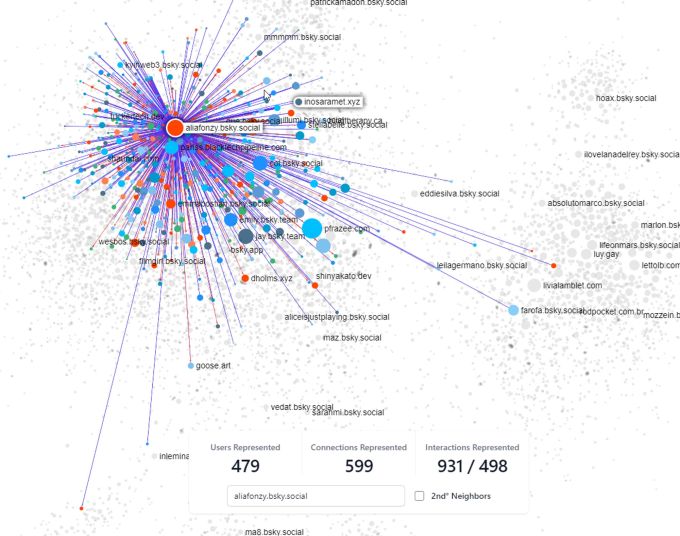

“If they want to know where it started, the hype of recent days? Black people. I think my invite tree can be testimony to that.” – Aveta, a software engineer who invited over 500 Black users to Bluesky. A social graph developed by Bluesky user Jaz shows Aveta’s connections.

“You know when you step out into a meadow and get that fresh breeze, that little breath of crisp air?” Aveta said “It’s exactly how it felt … I just want people to set the record straight, if they want to know where it started, the hype of recent days? Black people. I think my invite tree can be testimony to that.”

Black Twitter’s influence extends beyond Twitter itself, shaping humor and pop culture both online and in real life. Black creators typically create and spread trends across the internet, from choreographing viral TikTok dances to organizing digital activism. Guides to internet language often describe phrases like “ate this up” and “out of pocket” as “Gen Z slang,” which is misidentified and uncredited African American Vernacular English (AAVE.) “Gagged” and “slay,” for example, originated in the ballroom scene, the Black and Latino drag culture that emerged in 90s New York City.

In a 2016 essay for Model View Culture, Northwestern University professor Lauren Michelle Jackson noted that meme origins are often found in the “circulatory movement of Black vernacular itself.”

“Black folks are hardly the sole proprietors of internet memes, yet it’s undeniable that memes are at their liveliest — that is, which allows them to keep living — is in fact indebted to Black processes of cultural survival,” Jackson wrote.

Twitter is also unique because it allows nudity and sexually explicit content, unlike most major social platforms. The site has become a safe haven for sex work, and provides a centralized space for creators to advertise their services, interact with other sex workers and share vital resources with their community.

Sex work Twitter has existed since Twitter launched in the late 2000s, and grew as other online spaces became more hostile toward sexually explicit content. In 2018, U.S. law enforcement agencies shut down the classified ads site Backpage, and later that year, Tumblr banned porn. Sex workers flocked to Twitter, making that community one of the fastest growing subcultures on the platform.

Twitter is struggling to keep its active users. Last year, market research agency Insider Intelligence predicts that the site will lose more than 30 million users in the next two years. In April, data intelligence firm SimilarWeb reported that users are visiting Twitter less, with a 7.3% drop in worldwide visits in March.

Though interest in Twitter is waning, NSFW content is one of the only topics on the platform gaining interest among English-speaking users. (The other is cryptocurrency.)

But sex workers themselves are questioning whether Twitter will stay safe. After Musk’s takeover in October, many adult content creators expressed concern over losing the sex work community they built on Twitter. For now, Bluesky offers a promising alternative platform with decent moderation.

Olivia Snow, a dominatrix and research fellow at the UCLA Center for Critical Internet Inquiry, said Musk’s takeover disrupted marginalized communities and made it “more difficult to do literally any job” on the site because “the vibe sucks ass.” She’s hopeful that Bluesky’s moderation and content policies will pave the way for a less hostile social platform than Twitter has become.

“The main thing that I’m heartened by is the fact that they seem to have infrastructure in place for porn. It tells me that they are actually taking moderation seriously,” Snow said. “… Not in the way Twitter has started to, which is allowing whatever, and not the way that Instagram is super anti-sex. The way it’s set up will allow users to really customize their experience.”

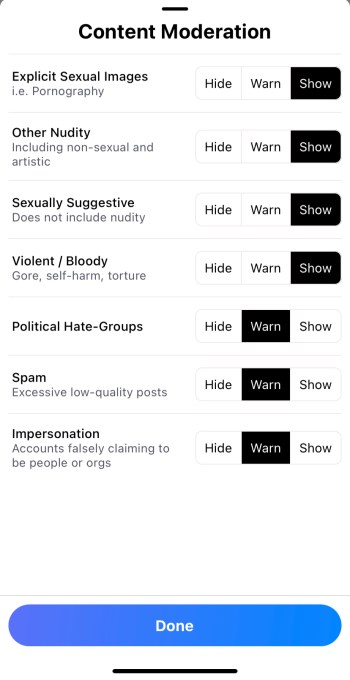

Bluesky allows users to set their own content moderation, providing an “infrastructure for porn.”

Bluesky not only allows explicit content, but also lets users choose the content they want to see. Users can toggle between seeing explicit content on their feeds, having a warning for sensitive content, or avoiding it all together. The platform also categorizes content as “explicit sexual images” like pornography, “other nudity” including non-sexual and artistic images, and “sexually suggestive” content that does not include nudity.

Natrix, a sex worker and NFT artist, was originally skeptical of censorship on Bluesky.

“I do think the lines between these categories can still be blurry, but that will always be the case with art and porn, as sexualization is so subjective,” Natrix said. “It will be interesting how things progress once the platform grows and how their detection system is fine-tuned, which they acknowledge is not yet perfect.”

The delineation is still clearer than Tumblr’s approach to easing content policies after its 2018 porn ban. Late last year, Tumblr started allowing nudity again, but not “depictions of sexually explicit acts,” causing confusion among users. Some adult content creators said their NSFW content was flagged even if it didn’t contain nudity.

“Giving users the option to choose which of these potentially sensitive categories they see, rather than outright banning or shadowbanning entire accounts, is still miles ahead of what we are used to on Twitter or Instagram, where sex workers are too often selectively punished for being sex workers more than for the content itself,” Natrix said.

Snow also questioned how Bluesky would handle doxxing. OnlyFans immediately bans users for sharing creators’ legal names, but no other social platform considers that to be doxxing. Meta Verified came under fire in sex work circles for requiring users to change their Instagram display name to the name on their government ID in order to receive verification.

Marginalized communities are usually responsible for building social media subcultures, but are also disproportionately moderated and harassed online. Black TikTok creators have repeatedly spoken out about how content discussing race and cultural appropriation appears to be censored on the app. Last year, a coalition of Black Twitch streamers penned an open letter to the company demanding better protection from harassment. And under Musk’s tutelage, hate speech on Twitter has skyrocketed.

If Bluesky aspires to be a viable alternative to Twitter, it needs to be better than Twitter was at its peak — and safer for marginalized users. In its nascent, invite-only phase, it’s already demonstrated that it will take action against hate speech. Over the weekend, Bluesky swiftly banned a user who harassed others with transphobic remarks.

Bluesky does appear open to fostering a sex worker community. Natrix noted that she received coveted invite codes (users usually only receive one code every two weeks, unless they’re gifted more by Bluesky staff) after she posted about wanting to bring more sex workers to the platform.

Though Bluesky doesn’t shun adult content, the platform does appear to be adding some restrictions on nudity. As of Monday, though, the platform has a “no boobs (or dicks, or asses)” on the discovery page policy, per a post from Bluesky technical advisor Jeremy Johnson. The goal, Johnson said, is for users to avoid nudity unless they deliberately opt in.

The platform may be safe for sex workers now, but like Tumblr, could take on more puritanical policies as it faces external pressure over time.

“We also know that sex workers often help to shape platforms and the way people use them, only to be pushed off later — but maybe the decentralized nature of it all will help when the going gets rough,” Natrix said.

Bluesky’s current draw is that it’s a more fun, less toxic version of Twitter. Plenty of would-be alternatives have emerged in the last year, each promising a newer, shinier user experience. Most have fizzled out as users either lost interest or grew horrified with the kind of rampant hate speech that also already exists on Twitter. By refusing to harbor hate speech, Bluesky is already distancing itself from Musk’s Twitter, but that commitment will truly tested when it starts onboarding more users.

Of course, keeping tabs on 40,000 users is nothing compared to moderating the hundreds of millions of users on a mature social network. It’s unrealistic to expect a platform to be free of conflict entirely, and even in its insular, invite-only mode, the site has already seen its fair share of discourse. Bluesky doesn’t need to be a utopian paradise for it to make a lasting impact, but it does need to establish guardrails to protect the vulnerable communities that are already shaping its culture — especially its Black users and sex workers. Booting transphobes from the site is a good start.