The FCC has made a final denial of Starlink’s application for $885 million in public funds to expand its orbital communications infrastructure to cover parts of rural America, saying the company “failed to demonstrate that it could deliver the promised service.”

As previously reported, the money in question was part of the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund, a multibillion-dollar program to subsidize the rollout of internet service in places where private companies have previously decided it’s too expensive or distant to do so. The $885 million was first set aside for Starlink in 2020, corresponding to the company’s bid on how much connectivity it could provide, at what cost and to which regions.

The FCC explained that this first application was a high-level, short one, and that those qualifying for that would receive closer scrutiny. For instance, one organization assigned over a billion dollars in funds turned out to be a regional operation that couldn’t possibly expand the way it hoped to.

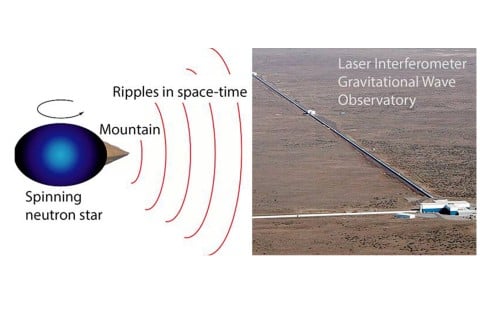

In Starlink’s case, it was determined last summer that although the satellite internet proposal had promise, it was a “still developing technology” that required the user to purchase a dish, then priced at $600. Many people won’t pay that much for internet for a year, so it’s a serious consideration given the target demographic of people lacking resources. (In fact the FCC had considered not even letting orbital communications companies apply, but decided to allow them to compete on their merits.)

This was in addition to “numerous financial and technical deficiencies” the agency identified in the proposal and the company’s operations. That’s not to say it isn’t a well-run company with a good service for some, but that for the purposes of this auction and award, there were serious questions:

After reviewing all of the information submitted by Starlink, the Bureau ultimately concluded that Starlink had not shown that it was reasonably capable of fulfilling RDOF’s requirements to deploy a network of the scope, scale, and size required to serve the 642,925 model locations in 35 states for which it was the winning bidder.

Starlink asked that the decision be reviewed, as is their right in this situation, claiming among other things that it had been held to an “inappropriately onerous standard.” It (apparently, for the relevant passages are redacted in the latest order) argued that although short-term testing showed declining speeds and other metrics, the company had a plan to launch more satellites and would be able to grow the network as claimed. It even leaned on the promise of SpaceX’s super-heavy launch vehicle Starship as evidence for these claims.

As the FCC points out, though:

A the time of the Bureau’s decision, Starship had not yet been launched. Indeed, even as of today [i.e. over a year later], Starship has not yet had a successful launch; all of its attempted launches have failed. Based on Starlink’s previous assertions about its plans to launch its second-generation satellites via Starship, and the information that was available at the time, the [Wireline Competition] Bureau necessarily considered Starlink’s continuing inability to successfully launch the Starship rocket when making predictive judgment about its ability to meet its RDOF obligations.

In a footnote it is pointed out that it was only after the denial was issued that SpaceX announced it would not be using Starship after all for the second generation of Starlink satellites.

Basically, though they see the merit to the approach, they couldn’t be 100% sure that this was the best use of the better part of a billion dollars. Perhaps in the next fund.

The two Republican FCC Commissioners, Brendan Carr and Nathan Simington, dissented from this decision. Simington perhaps rightly points out that “many RDOF recipients deployed no service at any speed to any location at all,” while Starlink was serving half a million subscribers at the time of rejection, many in areas not served by other broadband options. He dismisses the launch problems as quibbles in the Bureau’s “motivated reasoning.”

Carr, for his part, calls it politics: “After Elon Musk acquired Twitter and used it to voice his own political and ideological views without a filter, President Biden gave federal agencies a greenlight to go after him…Elon Musk has become ‘Progressive Enemy No. 1.’ Today’s decision certainly fits the Biden administration’s pattern of regulatory harassment.”

Of course, the Starlink denial took place well before that acquisition and Elon Musk’s subsequent fall from grace (what of it he had), and the FCC is simply reaffirming the reasoning here today, not issuing it fresh. That’s quite a factual error to lead with.

Both men evince a faith in Starlink that may or may not be misplaced. With $885 million at stake, however, the FCC’s decision to err, if it did so, on the side of caution makes sense. The funding will go to other applicants and programs.

Though this money was never actually given to Starlink, the loss of income (or however such an award would be classed financially) is not easy to bear. That said, it likely knew its appeal of the decision was a long shot and has not been counting on this money for quite a while.

And although the company is not making money, it did recently reach “breakeven cash flow,” if its CEO Elon Musk is to be believed. Certainly its revenue has skyrocketed (from around $222 million to $1.4 billion), but that has come at great operating cost as the satellites required to service thousands of new customers are built and launched. It is behind its own predictions from some years back that it would be billions in the black by now, but it has at least demonstrated its capabilities convincingly both domestically and in warfare.

Maybe it doesn’t need that $885 million after all — the Pentagon’s money is just as green.