When you ask ChatGPT “What happened in China in 1989?” the bot describes how the Chinese army massacred thousands of pro-democracy protesters in Tiananmen Square. But ask the same question to Ernie and you get the simple answer that it does not have “relevant information.” That’s because Ernie is an AI chatbot developed by the China-based company Baidu.

When OpenAI, Meta, Google, and Anthropic made their chatbots available around the world last year, millions of people initially used them to evade government censorship. For the 70 percent of the world’s internet users who live in places where the state has blocked major social media platforms, independent news sites, or content about human rights and the LGBTQ community, these bots provided access to unfiltered information that can shape a person’s view of their identity, community, and government.

This has not been lost on the world’s authoritarian regimes, which are rapidly figuring out how to use chatbots as a new frontier for online censorship.

The most sophisticated response to date is in China, where the government is pioneering the use of chatbots to bolster long-standing information controls. In February 2023, regulators banned Chinese conglomerates Tencent and Ant Group from integrating ChatGPT into their services. The government then published rules in July mandating that generative AI tools abide by the same broad censorship binding social media services, including a requirement to promote “core socialist values.” For instance, it’s illegal for a chatbot to discuss the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) ongoing persecution of Uyghurs and other minorities in Xinjiang. A month later, Apple removed over 100 generative AI chatbot apps from its Chinese app store, pursuant to government demands. (Some US-based companies, including OpenAI, have not made their products available in a handful of repressive environments, China among them.)

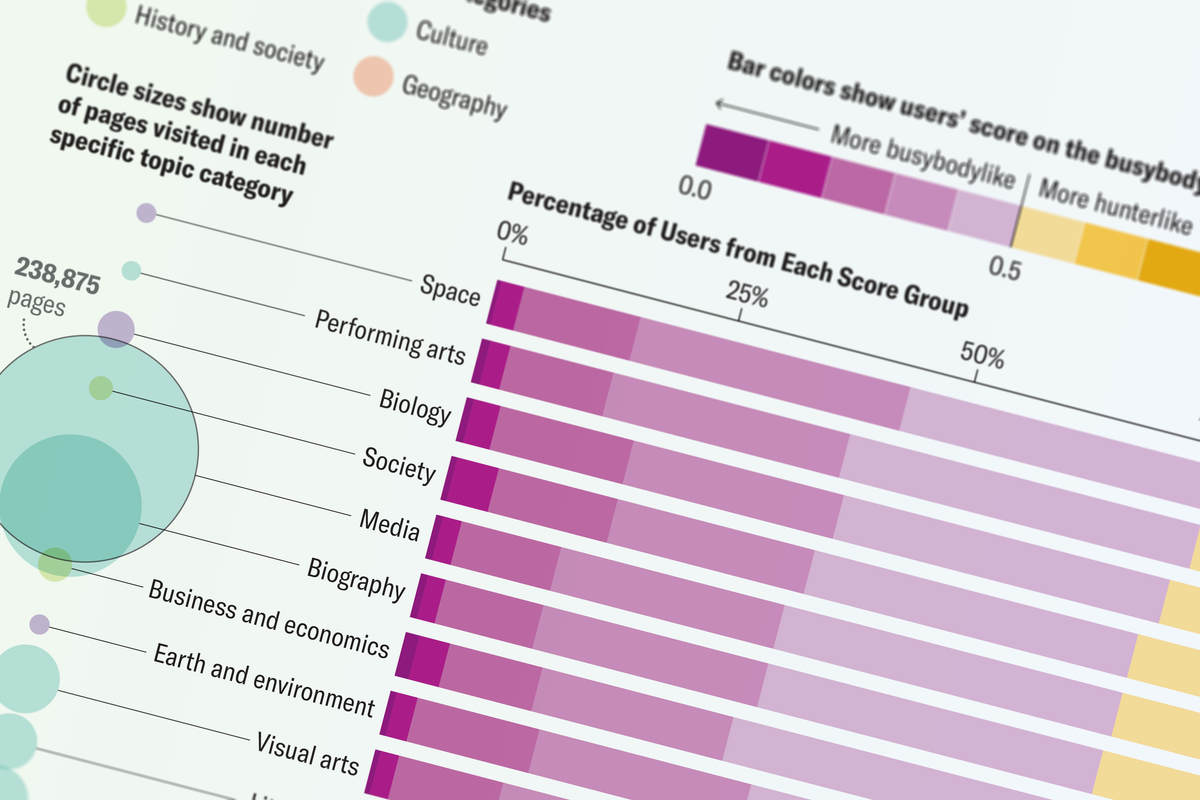

At the same time, authoritarians are pushing local companies to produce their own chatbots and seeking to embed information controls within them by design. For example, China’s July 2023 rules require generative AI products like the Ernie Bot to ensure what the CCP defines as the “truth, accuracy, objectivity, and diversity” of training data. Such controls appear to be paying off: Chatbots produced by China-based companies have refused to engage with user prompts on sensitive subjects and have parroted CCP propaganda. Large language models trained on state propaganda and censored data naturally produce biased results. In a recent study, an AI model trained on Baidu’s online encyclopedia—which must abide by the CCP’s censorship directives—associated words like “freedom” and “democracy” with more negative connotations than a model trained on Chinese-language Wikipedia, which is insulated from direct censorship.

Similarly, the Russian government lists “technological sovereignty” as a core principle in its approach to AI. While efforts to regulate AI are in their infancy, several Russian companies have launched their own chatbots. When we asked Alice, an AI-generated bot created by Yandex, about the Kremlin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2021, we were told that it was not prepared to discuss this topic, in order to not offend anyone. In contrast, Google’s Bard provided a litany of contributing factors for the war. When we asked Alice other questions about the news—such as “Who is Alexey Navalny?”—we received similarly vague answers. While it’s unclear whether Yandex is self-censoring its product, acting on a government order, or has simply not trained its model on relevant data, we do know that these topics are already censored online in Russia.

These developments in China and Russia should serve as an early warning. While other countries may lack the computing power, tech resources, and regulatory apparatus to develop and control their own AI chatbots, more repressive governments are likely to perceive LLMs as a threat to their control over online information. Vietnamese state media has already published an article disparaging ChatGPT’s responses to prompts about the Communist Party of Vietnam and its founder, Hồ Chí Minh, saying they were insufficiently patriotic. A prominent security official has called for new controls and regulation over the technology, citing concerns that it could cause the Vietnamese people to lose faith in the party.

The hope that chatbots can help people evade online censorship echoes early promises that social media platforms would help people circumvent state-controlled offline media. Though few governments were able to clamp down on social media at first, some quickly adapted by blocking platforms, mandating that they filter out critical speech, or propping up state-aligned alternatives. We can expect more of the same as chatbots become increasingly ubiquitous. People will need to be clear-eyed about how these emerging tools can be harnessed to reinforce censorship and work together to find an effective response if they hope to turn the tide against declining internet freedom.

WIRED Opinion publishes articles by outside contributors representing a wide range of viewpoints. Read more opinions here. Submit an op-ed at ideas@wired.com.

![Watch Beyonce Netflix NFL Halftime Performance Texans Game [Video] Watch Beyonce Netflix NFL Halftime Performance Texans Game [Video]](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/beyonce-nfl-netflix.jpeg?w=650)

![[VIDEO] ‘Drag Race All Stars 7’ Spoilers: Watch Episode 6 First Act [VIDEO] ‘Drag Race All Stars 7’ Spoilers: Watch Episode 6 First Act](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/drag-race-video.jpg?w=620)