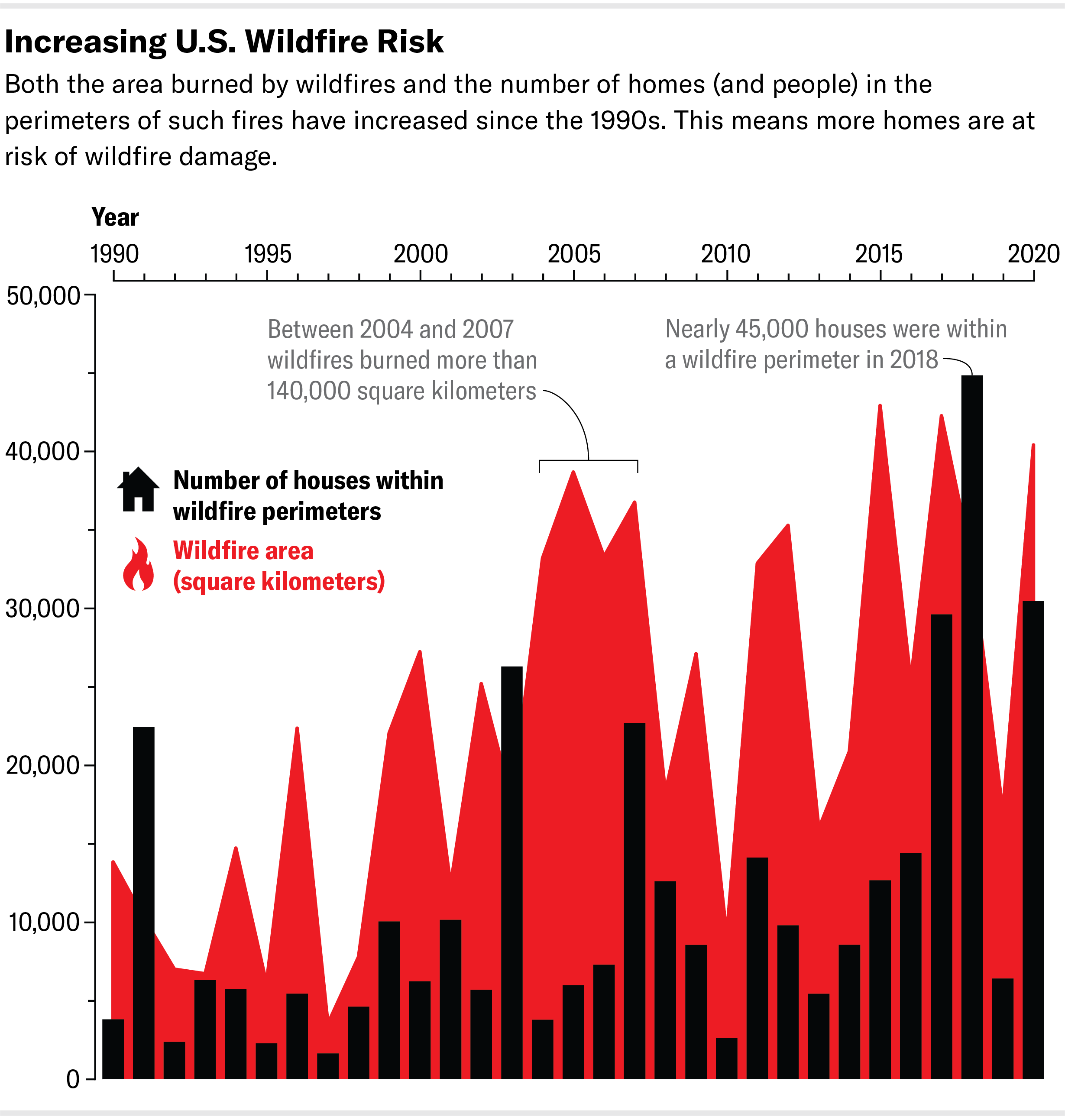

Smokey the Bear is famous for warning against forest fires—but for most U.S. homeowners, grass fires and shrubland fires are actually more of a threat. And there twice as many houses within the perimeters of wildfires today, compared with 30 years ago, meaning far more people and homes are at risk, according to a new study published on Thursday in Science.

Forest fires are well known for their ferocity. They accounted for just 33 percent of houses destroyed by wildfires in the early 2000s, however, the study authors found after analyzing the locations of homes within wildfire perimeters since the 1990s. In contrast, 64 percent of such houses were destroyed by grassland or shrubland fires. This is because even though forest fires are particularly destructive to buildings, much more of the area burned in the U.S. is made up of grasslands and shrublands, says the study’s first author Volker Radeloff, an ecologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “We had a hunch,” he says, “but the actual numbers surprised us.”

Grassland fires have been responsible for some of the most devastating losses in recent years. Fueled by strong winds, the fire that leveled the Hawaiian town of Lahaina in August tore through hillsides of invasive grasses—and became an urban conflagration that destroyed more than 2,000 structures and killed at least 99 people. In December 2021 the Marshall Fire in Colorado’s Boulder County destroyed more than 1,000 buildings and killed two people as it jumped from grasslands to suburban neighborhoods.

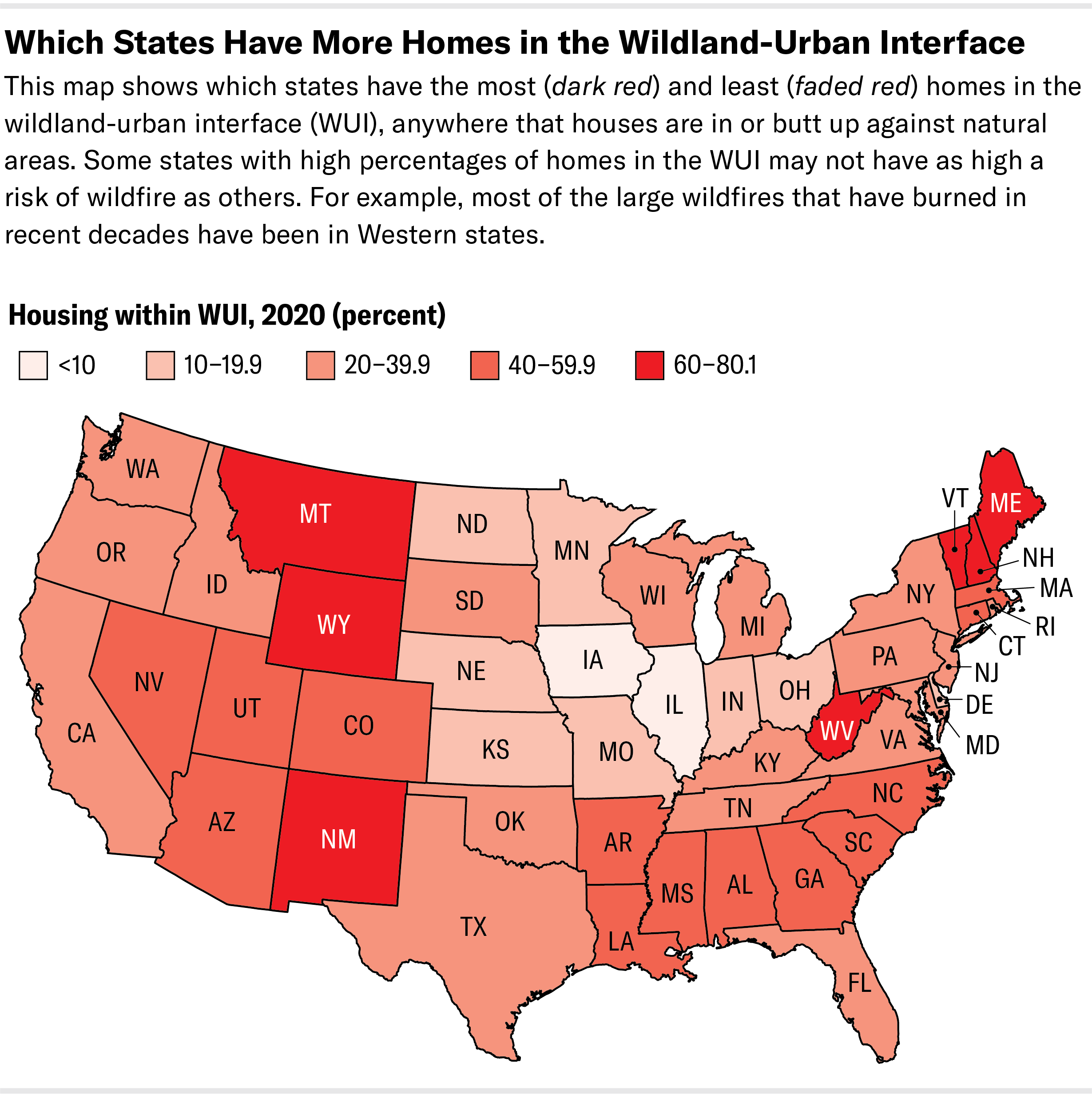

Two factors have contributed to the doubling of the number of homes within wildfire boundaries. Fifty-three percent of this effect could be blamed on an increasing amount of area burned: wildfires are more common and intense than they used to be. The other 47 percent was caused by the increased expansion of homes into what experts call the “wildland urban interface,” or WUI—anywhere that houses are in or butt up against natural areas.

Credit: John Knight; Source: “Rising Wildfire Risk to Houses in the United States, Especially in Grasslands and Shrublands,” by Volker C. Radeloff et al., in Science, Vol. 382. Published online November 9, 2023

The movement of more people into such places has compounding effects, says Timothy Juliano, a project scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo., who was not involved in the new study. Not only are more homes at risk from wildland fires; these environments now have more residents who might start a fire. “More people [means] more probability of these types of things happening,” Juliano says.

Between 1990 and 2020, the size of the WUI in the U.S. grew in area by 31 percent and the number of homes inside it grew by 46 percent. It now contains a total of about 44 million homes. Texas is currently the fastest-growing state for WUI housing, Radeloff says.

Homeowners in forested areas are often relatively well aware of their fire risk, says Sarah Anderson, a professor of environmental politics at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who was not involved in the new study. But people living next to a grassy or shrub-covered open space may not realize the danger. “This paper probably implies that we need to do a lot more public education,” Anderson says.

More than two thirds of U.S. buildings destroyed in wildfires were in the West, and 79.5 percent of buildings burned in them were in shrublands and grasslands, the researchers found. And the study may even underestimate these numbers because the researchers used a dataset for destroyed structures that only ran from 2000 through 2013. Thus, the analysis excluded several hugely destructive fires, such as the one in Lahaina, the Marshall Fire and the 2018 Camp Fire, a forest blaze that devastated the town of Paradise, Calif.

“California has lost 43,000 structures during the decade after this data was collected,” says Yana Valachovic, forest adviser and county director at the University of California Cooperative Extension in Humboldt and Del Norte Counties. “It would be good to see how that might change the statistics, let alone the losses in Colorado, Oregon and Washington [State], during this period.”

Credit: John Knight; Source: “Rising Wildfire Risk to Houses in the United States, Especially in Grasslands and Shrublands,” by Volker C. Radeloff et al., in Science, Vol. 382. Published online November 9, 2023

Regardless of the exact numbers, the study’s message is important, says Valachovic, who was not involved in the research. About 11 percent of homes that are exposed to wildfires are destroyed, according to Radeloff and his team’s analysis, and there are ways to improve the survival rate.

For example, Valachovic says, homeowners can protect themselves by screening vent openings so that embers can’t land in attics or eaves; by pulling vegetation and wood mulch away from foundations; and by installing metal panels to replace any sections of wood fencing that contact the house. (In the Marshall Fire, wood fences provided a pathway for the blaze to move between homes.)

Zoning regulations are another way to protect houses in the WUI, Valachovic says. Homes that are spread out and have lots of vegetation around them are less likely to catch fire if their neighbors go up in flames—but they are in increased contact with wildlands, where fires usually start. Plus, firefighters may struggle to respond in spread-out communities. WUI communities in which homes are clustered together have less exposure to wildlands. They may suffer when fire does find its way to a home, however, because the flames can easily spread from one house to another. There are tradeoffs to these styles of development, Valachovic says, and conversations around them need to happen.

“We’ve really got to talk about how you manage the landscape around your community,” she says, “but you’ve also got to talk about how to manage the community.”