Hurricane Beryl’s Unprecedented Intensification Is an “Omen” for the Rest of the Season

Hurricane Beryl exploded in strength from a tropical depression to a Category 4 major hurricane unusually early in its development in part because of exceptionally warm ocean waters

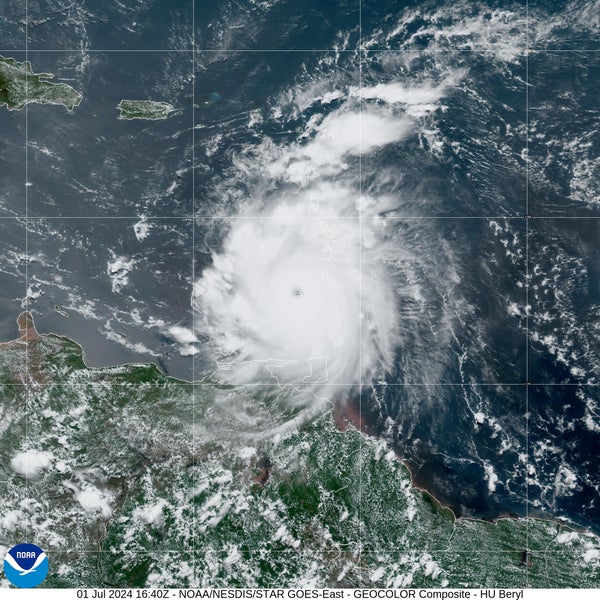

Hurricane Beryl rapidly intensified from a tropical depression on June 28 to a major Category 4 hurricane on July 1, the earliest Category 4 storm on record for the Atlantic Ocean basin.

A new tropical depression formed in the Atlantic Ocean last Friday. A mere two days later it had become a monstrous Category 4 hurricane and bore down on the Windward Islands. The storm made landfall in Grenada on Monday.

The occurrence of such rapid intensification this early in the Atlantic hurricane season and in that location has left meteorologists agog.

“Beryl is rewriting the history books in all the wrong ways,” wrote Eric Blake, a senior hurricane scientist at the National Hurricane Center (NHC), in a post on X (formerly Twitter).

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

And it likely won’t be the only exceptional hurricane this season, given the overall favorable conditions for storms to develop—especially the extremely warm ocean waters. “I think it is kind of an omen of what the hurricane season will be,” says Brian McNoldy, a hurricane researcher at the University of Miami. “I think we will see some pretty amazing outlier events happen.”

Prior to the official start of the Atlantic hurricane season on June 1, the NHC forecast that 17 to 25 named storms will likely occur by the time that season ends on November 30. (Storms receive a name once they reach tropical or subtropical storm strength, meaning they have winds of at least 39 miles per hour.) Of those, eight to 13 are expected to become hurricanes. And four to seven of those hurricanes will likely strengthen into major hurricanes (Category 3 or higher). This is the highest number of named storms the NHC has ever predicted; an average Atlantic season has 14 named storms, seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes.

Two main factors are at play in this outlook. First, there are exceptionally warm waters across the Atlantic, Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. Right now “the ocean temperatures out there look like they do at the peak of hurricane season” in the Atlantic in September, McNoldy says.

Then there is the current decay of the recent El Niño climate pattern and the possible development of a La Niña this year. The seesawing between these two climate patterns changes how heat is released into the atmosphere, which causes a domino effect on atmospheric circulation patterns. An El Niño leads to more wind shear over the Atlantic, which can rip storms apart, whereas neutral or La Niña conditions can make the atmosphere much more favorable to burgeoning hurricanes.

Given those factors, Beryl was exactly the kind of storm meteorologists were worried about. “Going into this season, this storm is one of the things we were talking about,” McNoldy says, in terms “of seeing storms form and intensify where and when they normally would not.”

Before Beryl, there has never been a hurricane known to form this far east in June, McNoldy says. The only other storm that came close was during the record-breaking 1933 season, before storms were given names. Beryl is also the earliest Category 4 hurricane on record for the Atlantic; the previous record-holder was Hurricane Dennis on July 8, 2005—during another blockbuster season. “That is not a couple of years that you want to be breaking records of,” McNoldy says. If Beryl becomes a Category 5 storm in the next day or two, he adds, it will break another record. The earliest Category 5 was Hurricane Emily on July 16, 2005.

Such strong hurricanes typically don’t form this early in the season or so far east because conditions are usually much less ripe for them. Ocean temperatures tend to be cooler this early in the summer. And the low-pressure systems that trickle off the western coast of Africa every few days—which can become the seeds of hurricanes—often encounter Saharan dust storms that quash storm development.

For similar reasons, Beryl’s massive burst of strength in such a short time is atypical of storms this early in the season. The only other comparable storms have occurred near or at the peak of the Atlantic season in August and September, when there is abundant ocean heat to fuel the convection that drives hurricanes. Rapid intensification is defined as when a storm’s winds jump by at least 35 mph in 24 hours. Beryl’s exploded by 63 mph over that same period. Several studies suggest more storms will undergo rapid intensification—and at faster rates—as the climate continues to warm.

Such a huge jump in strength in just a day or two can leave areas in the storm’s path unprepared for the onslaught. That is particularly the case in the Windward Islands, where major hurricanes are very rare. The last such storm to get within 100 miles of where Beryl struck was Hurricane Ivan, which hit Grenada as a Category 3 storm in 2004. “To call this anomalous would be a huge understatement,” McNoldy says.

Beryl may have wrought considerable damage in the Windward Islands. “It would be a terrifying thing here in Miami, where everything is a concrete block structure—it has the toughest building codes in the country,” McNoldy says. For these small Caribbean islands, “it can just completely wipe them out.”

Beryl likely won’t be the last storm to set records this season, as oceanic and atmospheric conditions that favor hurricanes expected to continue. “I do suspect that this is not going to be the last one of these that surprises us,” McNoldy says. “We have a long way to go.”