Editor’s Note (5/25/22): This article is being republished in the wake of a school shooting in Uvalde, Tex., that killed at least 19 children and two teachers. It was the deadliest such attack since the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., in 2012, and occurred less than two weeks after a deadly shooting in Buffalo, N.Y., that killed 10 Black people in an act of domestic terrorism.

When Illinois passed a law in 2014 permitting the concealed carrying of firearms—becoming the last of the 50 states to do so—Sam Rannochio opened Check Your 6, Inc. in the Chicago suburb of Arlington Heights. The store sells handguns and rifles, and also offers concealed-carry classes. “The two kind of go hand-in-hand together,” Rannochio says.

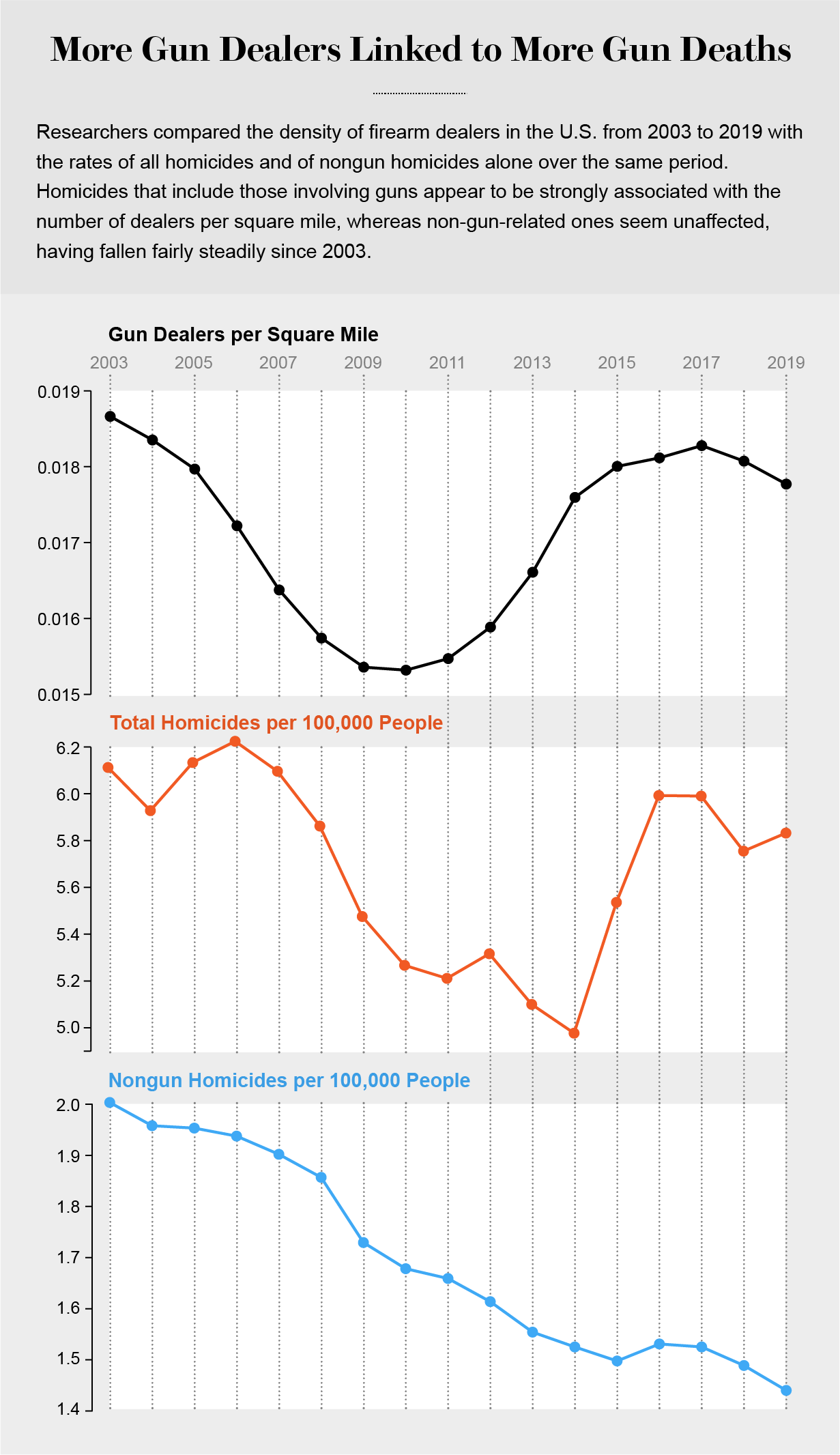

Check Your 6 was one of hundreds of gun dealerships that opened across the United States between 2010 and 2017, notes a preprint study that was published last month on social science research website SSRN and has not yet been peer-reviewed. According to the study, which looked at county-level data nationwide over a 17-year period, when the number of gun dealerships within 100 miles of a given area went up, the number of gun homicides in that area also increased in subsequent years—even as nongun killings declined overall (see graphic). Majority-Black communities bore the brunt of that violence, the study found.

The sharp rises in gun violence seen in some Black communities since 2014 have been widely attributed to the “Ferguson effect.” This term was coined by the then-chief of the St. Louis police, who claimed violent crime increases were driven by officers’ deteriorating morale following nationwide protests of the 2014 police killing of unarmed Black teenager Michael Brown in the St. Louis suburb of Ferguson, Mo. But the study authors propose these increases are linked to a steep rise in gun dealerships specializing in handgun sales near majority-Black communities shortly before 2014.

Before 2010 there had been “a massive decline in gun dealers,” says study co-author David Johnson, an economist at the University of Central Missouri. “Three, four years later, you start seeing declines in homicides—and then they pop right back up again once those gun dealers start reentering the market.” It is unclear what might have caused the number of dealerships to drop ahead of 2010, but the rebound in gun sales may have been driven by fears that then-President Barack Obama would enact strict gun-control policies, according to a 2015 study published in the Journal of Public Economics.

Gun availability is notoriously difficult to measure, partly because there is no federal registry of firearms. Previous studies have typically relied on gun suicide records, subscriptions to gun magazines, and survey data to estimate how many firearms are available in a given area. But the new study’s authors contend that these metrics are imprecise.

Instead, they used data on federal firearm licenses (which gun dealerships are required to obtain from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives) as a proxy measure of gun availability. The researchers compared this to FBI data, as well as statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Census Bureau, to track homicides for every U.S. county. Their analysis found that when a gun dealership opens, homicides within a surrounding area of 100 square miles increase by as much as 3.9 percent in subsequent years.

To help ensure they were not missing other factors that could have driven increases in both gun stores and homicides, the researchers also looked at killings that did not involve a firearm—and found such “nongun homicides” decreased during the study period. “If the effect on homicides was not being driven primarily by the guns themselves, then we would expect nongun homicides to be correlated with gun stores as well, which we show they are not,” Johnson says. “The increase in homicides is happening largely through the increase in gun availability.”

Daniel Webster, who directs the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Prevention and Policy and was not involved in the new study, says it raises the question of how to uniformly regulate gun shops. “There’s enormous variability from one gun dealer to another in terms of the rate at which the guns they sell end up being used in a crime,” he says. “I think that’s not a function of chance. It’s a function of how people run their businesses.” He suspects that tighter regulations on gun shops, along with more oversight of dealerships, would reduce gun crimes.

Illinois has some of the country’s strictest gun laws, according to a gun-control advocacy organization called Giffords Law Center, and there are no licensed gun dealers in Chicago. Yet the city remains awash in firearms and is plagued by gun violence. Chicago is less than 100 miles from Wisconsin, Michigan and Indiana (the latter borders the city itself), and all three have far fewer gun restrictions than Illinois.

The SSRN study highlighted Chicago for this very reason, also noting that the city has a surrounding “halo” of Illinois counties where gun dealerships are concentrated. As a result, Chicagoans need not travel far to legally buy a firearm. “Gun dealers introduce more guns into the community,” says study co-author Joshua Robinson, an economist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. And that increased availability is not limited to law-abiding buyers.

“There have been instances where people have come in [to the store] with bad intentions,” says Rannochio, the gun shop owner. “You’re always going to have someone trying to purchase a firearm for someone else, illegally—what they call ‘straw purchasing.’” He adds that state-mandated background checks and his own law-enforcement experience help guard against this (he was a police officer for 20 years in Skokie, an affluent, majority-white village that borders Chicago), and he recalled two instances in which he says he declined to sell a gun to prospective buyers. As far as he knows, he says, none of the firearms Check Your 6 has transferred or sold wound up being tied to any crime.

Still, firearms bought (or stolen) from other licensed dealerships in the suburbs and surrounding states frequently turn up in Chicago shootings. In one recent high-profile case, a gun allegedly purchased by an Indiana resident in that state’s city of Hammond, which borders Chicago, was used in the fatal shooting of a Chicago police officer. In another, a man in Indianapolis allegedly bought a gun that was used to kill a seven-year-old girl on Chicago’s West Side.

“That’s why you keep hearing about straw purchases,” says Wallace “Gator” Bradley, a former enforcer for the Gangster Disciples, a major Chicago street gang. “Individuals that have a right to go buy a gun will go to the gun stores or go to the gun shows and buy the guns. They come right back.” He adds that purchasers do not have to cross the state line to do so. “You can go right to one of the suburbs … and go buy a gun.”

Bradley, who was pardoned by Illinois’ Republican Governor Jim Thompson in 1990 and has been a peace advocate for decades, says he thinks straw purchasers should be charged with murder in shootings that involve guns they distribute. Rannochio also says he thinks the solution is tougher prosecutions. “It’s not the gun dealers that are causing the problems,” Rannochio says. “It’s the criminals committing crimes with the guns that they’re not even supposed to have.” In a statement e-mailed to Scientific American, Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx, a progressive reformer who has overseen prosecutions in Chicago since 2016, says her office is addressing just that. Foxx’s office has prosecuted 5,076 gun cases so far this year, with a conviction rate of 73 percent.

“We need to make sure that we’re holding gun shops and gun manufacturers accountable,” says Kina Collins, a gun-violence prevention advocate who is primarying Congressman Danny Davis in Illinois’ 7th District—which includes some of Chicago’s hardest-hit neighborhoods, as well as parts of suburbs where gun dealerships are located. “And we need to make sure we’re in communication with other leaders in Midwestern states, because we’re seeing a flow of illegal guns continuously cross our state lines,” Collins adds. “Grassroots, we need to make sure we’re funding violence-interruption programs, because we know they work.”

On Monday, Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker called gun violence a “public health crisis” and announced the formation of a new statewide office for gun violence prevention. Pritzker vowed to earmark $250 million in state and federal funds to address the issue.

GoodKids MadCity, a Chicago youth organization that advocates for noncarceral solutions to gun violence, argues that communities plagued by violence need less aggressive policing and more government investment to undo years of damage wrought by what it calls racist policies. The group has for years promoted a package of proposals collectively called the Peace Book Ordinance, which would divert 2 percent of Chicago’s annual police budget of around $1.7 billion to fund services such as mental health and substance abuse treatment.

Webster says such holistic approaches are crucial to mitigating violence. “There are some communities where disinvestment is substantial, and a lot of the systems—schools, transportation, housing, policing—are failing,” he says. “By policy and structure, people who are Black are more concentrated in those neighborhoods. And that is intentional. It is a function of public policy over generations.”

Bradley says any solution requires entire cities to stand together against gun violence. “No one person, outside of God, can stop it all,” he says. “And you know it like I know it: America is the biggest arms dealer in the world.”