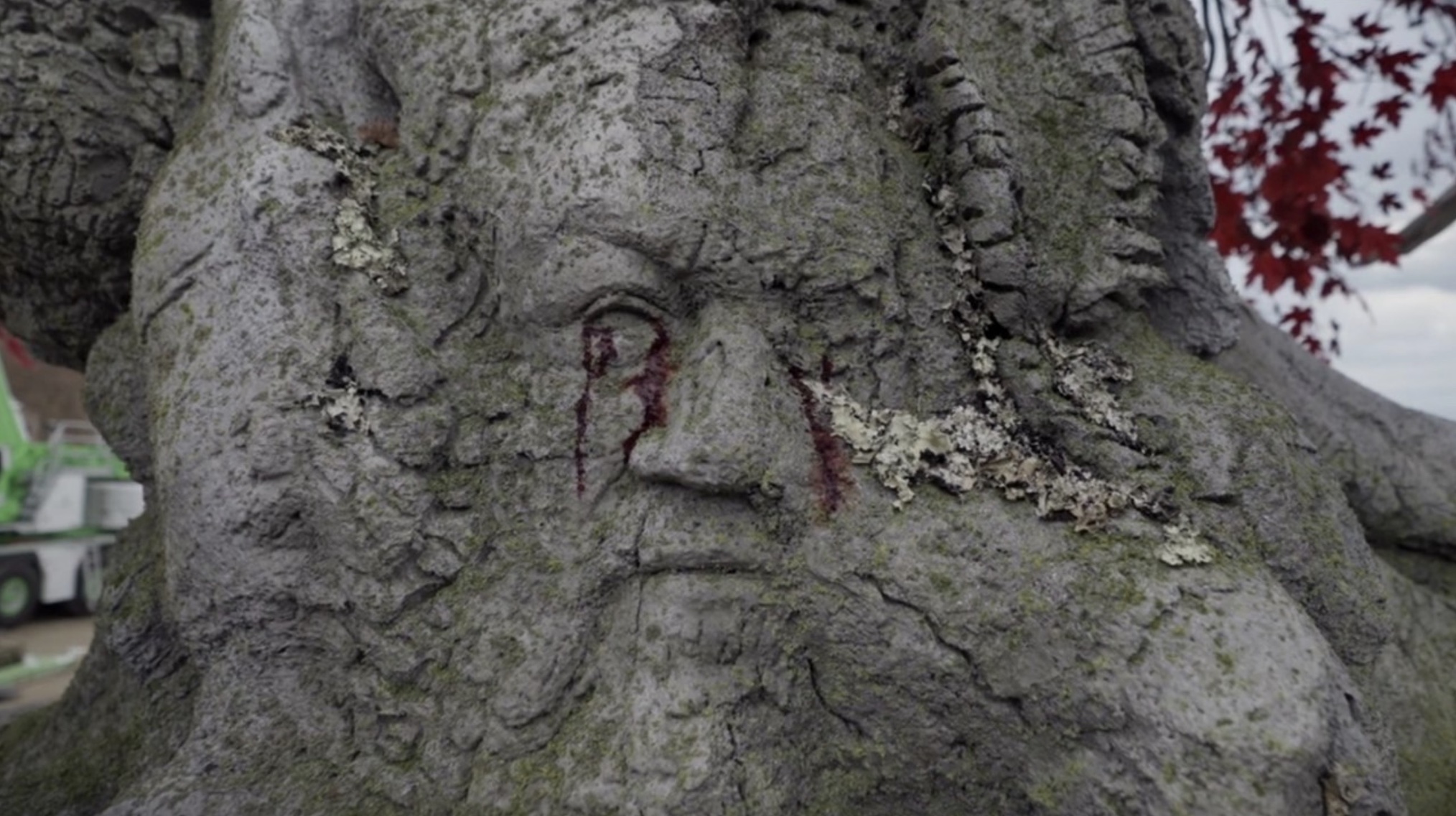

Invasive species introduced by humans to new regions can also be markers, the scientists said. The inadvertent import of alien species in the ballast water of ships arriving in San Francisco from Asia transformed the San Francisco Bay. “There was a point where 98 percent of the mass of all of the animal species in the bay were actually invasive,” Waters said. Pollen from introduced plant species, such as the trees used in commercial forestry, can also record change.

Chemical and metal pollution show up in sediments too, said Turner: “The Green Revolution was based on artificial fertilizers and pesticides, and so you see that in sediment cores. The whole cocktail of industrial chemicals just exploded postwar.” Whether the chemicals persist in the environment long enough to be markers of the Anthropocene remains to be determined.

The 12 potential locations for the site that will define the new epoch all display some of the markers, but they are very varied. “Because the Anthropocene has not been formally accepted, we’re still trying to prove to people that this is not something localized, it is something you find and correlate in a whole host of different environments,” said Waters.

“They all illustrate this dramatic Anthropocene transformation very well. But the sites which really stand out are the ones where you can actually see an annual resolution of layers,” said Turner, including some of the lake, coral, and polar ice sites. “It’s quite astonishing that these sites detail planetary changes at annual resolutions.”

All have pros and cons. The 32-meter-long Palmer ice core from the Antarctic Peninsula is the longest record of the Anthropocene, but its remote location means the trace of some of the markers is often faint. The Baltic Sea sediments switch from pale to black as the Anthropocene starts. This is caused by pollution-fueled algal blooms sucking all the oxygen out of the water. But the sediments do not have annual laminations. The archeological site in central Vienna gives a 200-year record, dated by artefacts, but has gaps in the record because of redevelopments.

The choice of site, and therefore the official time and place for the dawn of the Anthropocene, is in the hands of the 23 voting members of the AWG, but it will then have to be passed by the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy, then the International Commission on Stratigraphy, and finally be ratified by the International Union of Geological Sciences. There is a deadline too: the International Geological Congress in South Korea in 2024, when the mandate of the AWG expires. “It’s been pretty much stated that we’ve got until then to get this done,” said Waters.

Naomi Oreskes, a professor at Harvard University and a nonvoting AWG member, said: “As geologists, we were trained to think that humans were insignificant. That was once true, but it no longer is. The evidence compiled by the AWG demonstrates beyond any doubt that the human footprint is now in evidence in rocks and sediments. The Anthropocene is primarily a scientific concept, but it also highlights the cultural, political, and economic implications of our actions.”

UCL’s Mark Maslin, who coauthored The Human Planet with Simon Lewis, said: “I think the Anthropocene is a critical philosophical term, because it allows you to think about what impact we are having, and what impact we want to have in the future.”

Maslin and Lewis previously proposed 1610 as the start of the Anthropocene, representing the huge and deadly impact European colonists had on the Americas and consequently the world. But Maslin said agreeing on a definition was more important than precisely where it is placed.

“Up until now, we have talked about things like climate change, the biodiversity crisis, the pollution crisis as separate things,” he said. “The key concept of the Anthropocene is to put that all together and say humans have a huge impact on the earth, we are the new geological superpower. That holistic approach then allows you to say: ‘What do we do about it?’”