Nonfiction

Uncontrolled Burn

Absurdity reigns when a wildfire threatens a town purpose-built for oil extraction

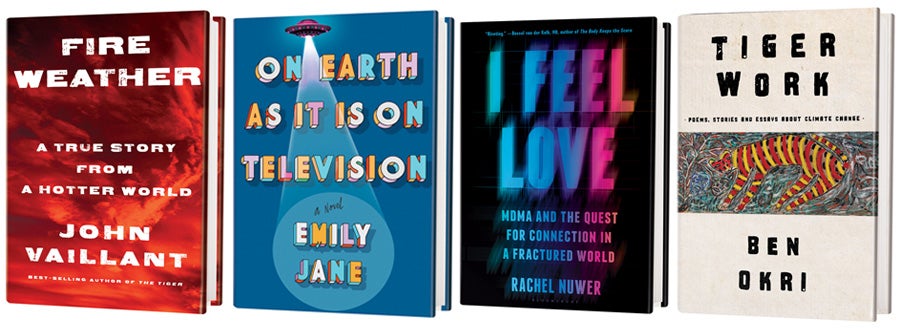

Fire Weather: A True Story from a Hotter World

by John Vaillant

Knopf, 2023 ($32.50)

In May 2016 a wildfire started near Fort McMurray, the boomtown built around the oil sands in Alberta, Canada. The fire grew to almost 1.5 million acres and became its own kind of weather system, creating fearsome pyrocumulonimbus clouds that made their own lightning. It was a vivid modern allegory: a blaze of biblical proportions threatening one of humanity’s greatest acts of hubris.

Few writers were better positioned to tell the story than John Vaillant, a Vancouver-based journalist and novelist who is at his best in the fraught places where desperate humans clash with their habitats. Vaillant’s gorgeous first book, The Golden Spruce, centers on an act of eco-sabotage in the Haida Gwaii archipelago in Canada, and he rose to wider prominence with The Tiger, a bestselling account of a predator that seemed to take vengeance on hunters in eastern Russia. In Fire Weather, Vaillant travels to a city where money rules, nature is an object of conquest, and a ridge on the land has been “weeping raw bitumen that glistened like liquid obsidian.”

Meanwhile North America is caught in a human-made wildfire deficit because a century of suppression has created dense layers of timber primed to burn. In Alberta’s subarctic boreal forests, thick with spruce and aspen, those fires are often massive. “When it burns, it goes off like a carbon bomb,” Vaillant writes.

To narrate the events of the summer of 2016, Vaillant reconstructs the actions of an oil-sands employee, multiple firefighters and the much maligned emergency-response leadership, among others. Their experiences contain ample drama, but their lives rarely connect. Fort McMurray, like many boomtowns, is a transient place. “Nobody retires here, nobody dies here,” a pastor named Lucas Welsh tells Vaillant. They also don’t seem to interact that much. In this relational void, where the story often feels fractionated rather than woven, the wildfire itself emerges as the book’s main character. The choice feels intentional—the blaze’s fury has a thematic resonance with the tiger’s—and Vaillant goes to great lengths to demonstrate that humans have invited a comeuppance. “Miles above the city, hurricane-force downdrafts hurled fusillades of black hail back to earth,” Vaillant writes, “just as they had done in ancient Egypt.”

In recent years some journalists who write about wildfires have begun avoiding this supercharged language of aggression. The ingrained Western tendency to characterize wildfire as invading and monstrous reinforces a colonial assumption that we can live apart from what is a natural and regenerative force. Vaillant repeatedly frames the fire in explosive or biblical terms and the subsequent effort to save Fort McMurray as a war, with firefighters pitted against the flames. The effect is certainly dramatic, and it underscores his central point that megafires such as this one are not entirely natural and are exacerbated by oil-driven greed. “If unregulated free market capitalism were a chemical reaction,” he writes, “it would be a wildfire in crossover conditions.”

His reporting on the phenomenon of “crossover”—described here as the moment when temperature surpasses relative humidity and a blaze is unleashed— is captivating, as is the insight that the combustive energy released in Fort McMurray was comparable to a nuclear bomb’s. But Vaillant also characterizes the wildfire as a “regional apocalypse” and imminent flashover—the point of spontaneous combustion in an enclosed space—as “a malevolent entity from another dimension breaking through to this one.”

In The Tiger, Vaillant toed an awfully fine line to take the reader inside the cat’s mind, using science reporting and a rigorous story structure to propel a thriller of natural history. In Fire Weather, there are fewer narrative guardrails, and as a result the book can feel meandering, with digressions that seem indulgent. One chapter is dedicated to the idea, proposed by Vaillant, that the human species should be renamed Homo fraglans, liberally translated as “burning man.” There are epigraphs from Ovid, Herman Melville and Shakespeare; when one from Cormac McCarthy’s The Road appears at the top of another chapter, it feels almost inevitable.

In moments of focus, Fire Weather is animated by a fascinating history of regional exploitation and illustrative absurdities from a get-rich-quick city burning down. A fleeing resident insists on locking his door as flames engulf his street; a golfer, freshly evacuated from the course, stops to pick up his dry cleaning; a student actually tells her brother, “Don’t look up!”

There’s a memorable character named Wayne McGrath, one of many Newfoundlanders who came to Fort McMurray after the collapse of the cod industry—an earlier environmental fiasco created by capitalistic appetites. McGrath goes to astonishing efforts to save a beloved Harley-Davidson before riding into the sunset.

McGrath’s troubling story doesn’t end there, and it alone might have been enough to anchor the narrative—as might the experiences of the firefighters who courageously fought the blaze when, as Vaillant beautifully writes, “even the ravens had fled.”

But Vaillant seeks to wrangle something still more grandiose from the material, and in his frustration with our collective failures, he leaves behind many of his characters. He is not the first great writer to point out that, in an age of greed, we could all do with more restraint. He’s also not the first to veer into unrestrained activism at the expense of a story—one that, in this case, was powerful enough on its own merits. —Abe Streep

Abe Streep is a journalist based in Santa Fe, N.M., and author of Brothers on Three: A True Story of Family, Resistance, and Hope on a Reservation in Montana (Celadon, 2021).

Fiction

Invasion Meme

An alien-induced existential crisis in the online age

On Earth as It Is on Television

by Emily Jane

Hyperion Avenue, 2023 ($27.99)

Glittering, strange spaceships appear and hover over every major city on Earth; yes, that’s familiar. What is unfamiliar about this debut from Emily Jane is the way first contact with an alien species brings people together and how it tears them apart—as well as the major role of cats.

Written for an extremely online age, On Earth as It Is on Television follows a handful of characters, each of whom must decide who they will be in a world fundamentally changed by the knowledge that we are not alone and are never unwatched. It brings readers into the mind of a long-comatose man named Oliver, whose first hint of consciousness in 20 years coincides with the invasion. It grants a beguiling window into the marriage of Blaine and his wife, who look perfect from the outside but start to disintegrate the minute the world changes. It asks deep questions about what constitutes a meaningful life through Heather, a woman who realizes she mostly has not lived one, so far.

The novel also follows the epic adventure of a “chonky boi” cat named Mr. Meow-Mitts, who receives a mysterious message to “run run run” toward a gathering of cats when the aliens land. The language of cat adoration is spread thick, as charming as buttercream and equally sweet.

If you enjoyed Lindsay Ellis’s Axiom’s End but prefer lighter fare, you’ll find deep comfort and joy in Jane’s exploration of what it means to be alien and how we all take turns being on the outside. Like a science-fiction novel that runs in the margins of I Can Has Cheezburger? memes, On Earth as It Is on Television is an unusually fun and absurd take on what might otherwise be just another imitation of Independence Day or The Day the Earth Stood Still. It is smart about consumer culture and the American yearning to turn everything into reality TV without using those smarts to bite. In this way, Jane’s work is a fine example of what is often called noblebright fiction (as an alternative to the subgenre of grimdark): it serves up heart, but nobody had to be cut open to obtain it. —Meg Elison

In Brief

I Feel Love: MDMA and the Quest for Connection in a Fractured World

by Rachel Nuwer

Bloomsbury, 2023 ($28.99)

If you’re looking to parse the hype about MDMA, this excellently researched book by Scientific American contributor Rachel Nuwer gathers perspectives from skeptics and supporters alike: law enforcement, psychiatrists, and people with past and present experience taking the drug. Nuwer’s journalistic instinct to cover warnings of its possible physiological effects and to advocate for law-abiding behavior cleverly plays off her analysis of the political broadsides that have long maligned the drug’s reputation. The compelling narrative, woven from emotional testimonials and clinical studies, makes a convincing argument for MDMA’s potential as a therapeutic supplement, especially for those working through trauma. —Sam Miller

Tiger Work: Poems, Stories and Essays about Climate Change

by Ben Okri

Other Press, 2023 ($24.99)

Rejecting the term “climate emergency” in favor of “humanity emergency,” Ben Okri puts forth an indictment of humanity that is counterbalanced only by his belief in its capacity for evolution. Although his collection is diverse—it includes poems about plastic, parables about water, a letter to Earth and vignettes describing our civilization in its waning days—Okri’s simple, stirring language runs through it like a current, delivering unexpected shocks of both pain and inspiration. Imbued with an “existential creativity to serve the unavoidable truth of our times,” this volume offers an unflinching vision of who we are and who we must become to survive. —Dana Dunham