About 40% of the world’s civilian-owned firearms are in the United States, a country that has had some 1.4 million gun deaths in the past four decades. And yet, until recently, there has been almost no federal funding for research that could inform gun policy.

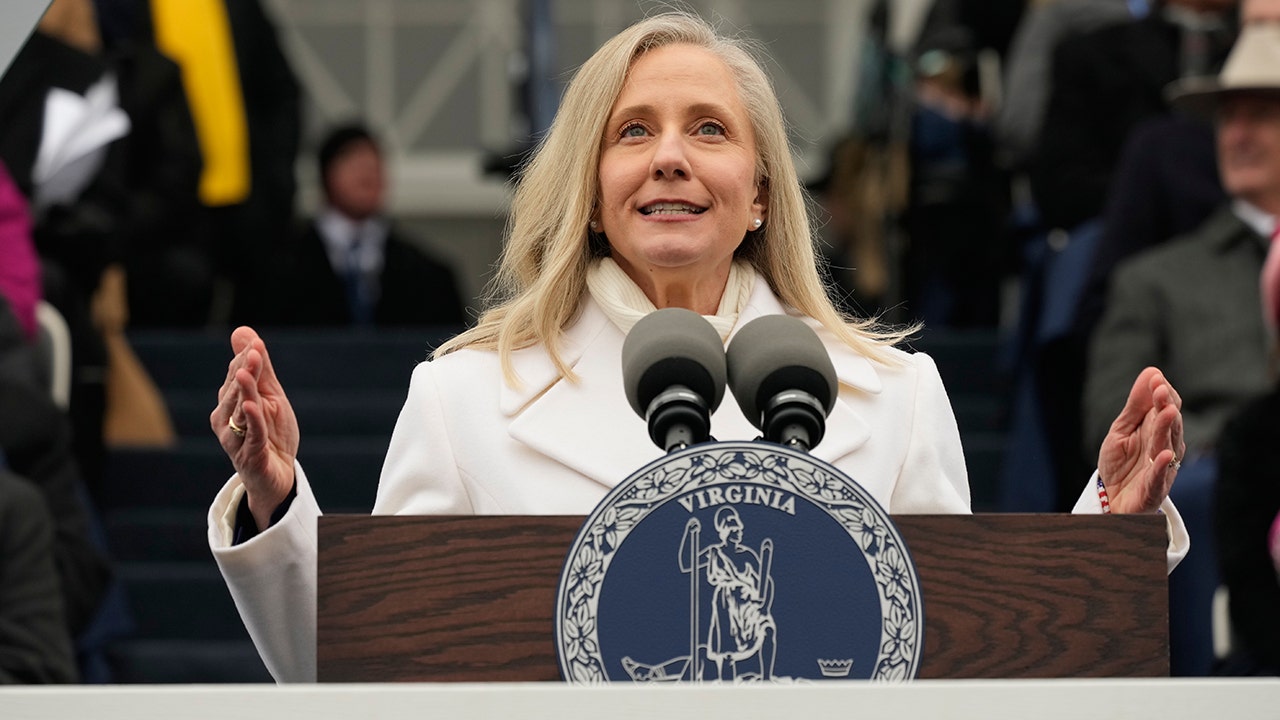

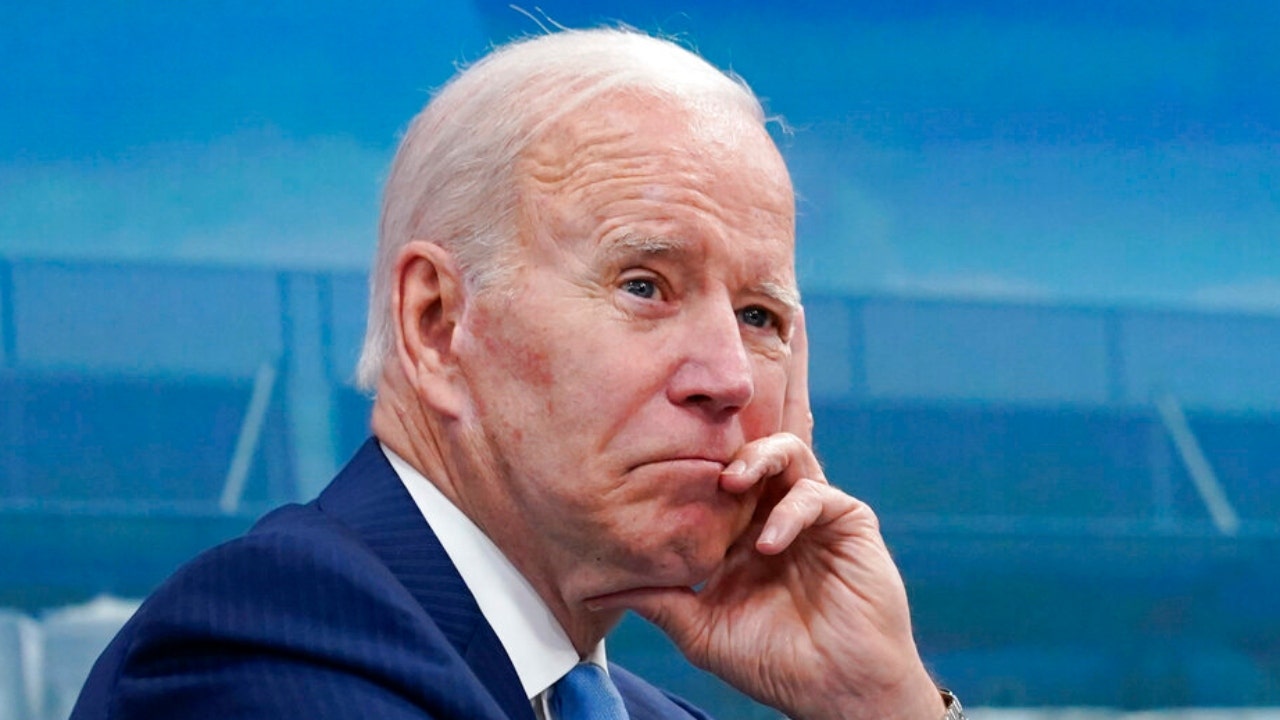

US gun violence is back in the spotlight after mass shootings this May in Buffalo, New York, and Uvalde, Texas. And after a decades-long stalemate on gun controls in the US Congress, lawmakers passed a bipartisan bill that places some restrictions on guns. President Joe Biden signed it into law on 25 June.

The law, which includes measures to enhance background checks and allows review of mental-health records for young people wanting to buy guns, represents the most significant federal action on the issue in decades. Gun-control activists argue that the rules are too weak, whereas advocates of gun rights say there is no evidence that most gun policies will be effective in curbing the rate of firearm-related deaths.

The latter position is disingenuous, says Cassandra Crifasi, deputy director of the Center for Gun Violence Prevention and Policy at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. Although some evidence, both from the United States and overseas, supports the effectiveness of gun policies, many more studies are needed. “The fact that we have a lot of unanswered questions is intentional,” she says.

The reason, Crifasi says, is mid-1990s legislation that restricted federal funding for gun-violence research and was backed by the US gun lobby — organizations led by the National Rifle Association (NRA) that aim to influence policy on firearms. Lars Dalseide, a spokesperson for the NRA, responds that the association “did support the Dickey Amendment, which prohibited the CDC [US Centers for Disease Prevention and Control] from using taxpayer dollars to conduct research with an exclusive goal to further a political agenda — gun control.” But he adds that the association has “never opposed legitimate research for studies into the dynamics of violent crime”.

Only in the past few years — after other major mass shootings, including those at schools in Newtown, Connecticut, and Parkland, Florida — has the research field begun to rebuild, owing to an infusion of dollars and the loosening of limitations. “So, our field is much, much smaller than it should be compared to the magnitude of the problem,” Crifasi says. “And we are decades behind where we would be otherwise in terms of being able to answer questions.”

Now, scientists are working to take stock of the data they have and what data they’ll need to evaluate the success of the new legislation and potentially guide stronger future policies.

Data gaps

Among the reforms missing from the new US law, according to gun-safety researchers, is raising the purchasing age for an assault rifle to 21 years. Both the Buffalo and Uvalde gunmen bought their rifles legally at age 18. But making the case for minimum-age policies has been difficult because there are few data to back it up, Crifasi says. “With the limited research dollars available, people were not focusing on them as a research question.”

Gun-violence research is also stymied by gaps in basic data. For example, information on firearm ownership hasn’t been collected by the US government since the mid-2000s, a result of the Tiahrt Amendments. These provisions to a 2003 appropriations bill prohibit the US Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives from releasing firearm-tracing data. For researchers, this means not knowing the total number of guns in any scenario they might be studying. “If we want to understand the rate at which guns become crime guns, or the rate at which guns are used in suicide, and which kind of guns and where, then we have to have that denominator,” says John Roman, a senior fellow at NORC, an independent research institution at the University of Chicago, Illinois.

Accurate counts of gun-violence events — the numerators needed to calculate those rates — are hard to come by, too. The CDC provides solid estimates of gun deaths, researchers note, but the agency hasn’t historically provided important context, such as the kind of weapon used or the relationship between the shooter and victim. Now fully funded, the state-based National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) is beginning to fill in those details. Still, it remains difficult for researchers to study changes over time.

What’s more, most shootings do not result in death, but still have negative impacts on the people involved and should be tracked. Yet CDC data on non-fatal firearm injuries are limited to imperfect summary statistics and are not included in the NVDRS. If researchers were better able to examine shootings beyond firearm deaths, they could have much greater statistical power to evaluate the effects of state and federal laws, Crifasi says. Without enough data, a study might conclude that a gun policy is ineffective even if it actually does have an impact on violence.

“The CDC strives to provide the most timely, accurate data available — including data related to firearm injuries,” says Catherine Strawn, a spokesperson for the agency.

Another complicating factor is that primary sources of gun-violence data — hospitals and police departments — issue statistics that are incomplete and incompatible. Hospitals frequently report intentional gunshot injuries as accidents. “Folks in the ER are not criminal investigators, and they default to saying things are accidents unless they absolutely know for certain that it was an intentional shooting,” Roman says.

Data on gun-related hospital care — which are collected under an agreement between the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, states and industry — can also be difficult for researchers to access. Some states charge for access to their data. “To get the complete set is incredibly expensive for researchers, so no one uses it,” says Andrew Morral, director of the National Collaborative on Gun Violence Research at the RAND Corporation in Washington DC. “The federal government could do better at aggregating data and making it available for research.”

In addition to hospitals, police departments are crucial to the collection of accurate gun-violence data. In 2021, the FBI began requiring all local law-enforcement agencies to report crimes to the National Incident-Based Reporting System. Although users are required to input more-comprehensive data to the system than before, compliance among departments has been low. “You have very, very active data collection at every scene of every traffic accident that involves an injury,” says Philip Alpers, a gun-violence researcher at the University of Sydney in Australia, referring to standard reporting protocols for US paramedics and police. So it’s certainly possible for law-enforcement agencies also to collect information about guns, Alpers adds. But he and others suggest that a culture of gun rights among agency personnel could be disincentivizing them from complying, as well as a lack of financial support for adapting to the new system.

The FBI did not respond to Nature’s queries about the reporting system.

Looking for lessons from abroad

Researchers emphasize that the call for more data and research is no reason to delay implementing gun controls. After all, some data do exist, from international studies on gun safety and from state- and privately funded US investigations, that could guide policymakers.

For instance, in Israel, policy changes that restrict military personnel from bringing their weapons home resulted in reductions in gun suicides. And after a mass shooting in Port Arthur, Australia, in 1996, officials imposed a suite of gun regulations centred around a massive buyback programme. The country approximately halved its rates of gun homicides and suicides over the following seven years. It also had no mass shootings in the subsequent 2 decades, compared with 13 such incidents in the 18 years leading up to the massacre.

Still, these successes might not translate to the United States. “Could America do what Australia did? The answer is no, not a chance. You’ve got too many guns [in the US],” Alpers says. “You have to separate America from the rest of the world.” And, with the prospect of tightened regulation on the horizon, US firearm ownership seems to be rising: gun stores around the country are seeing increased sales.

“We can learn from [other countries’ experiences],” Roman says. “But that seems so far outside of any reasonable expectation of where US policy is headed.” In other words, the United States needs more research.

Slow, belated progress

The good news is that data collection in the United States has been on the rise since the influx of federal funding. Researchers and others will meet at the first National Research Conference on Firearms Injury Prevention, planned for later this year.

This revived interest in gun-safety research will bolster the sparse efforts across the country that relied mainly on state and private funds. For instance, California initiated a restriction on assault weapons in 1989, and has since layered on other regulations, such as universal background checks and red-flag laws that allow police, family members, employers, co-workers and school employees to petition the court to temporarily separate a person from their firearms.

For the past 22 years, California’s gun-death rate has been trending downwards, explains Garen Wintemute, an emergency-medicine physician at the University of California, Davis. In 2020, the overall rate across the other 49 states was around 64% higher than the rate in California. Although it is difficult to tease apart the impacts of individual laws, the sum total seems to be working. “I suspect that they acted synergistically: where one law wasn’t effective, the other one stepped in,” Wintemute says.

A similarly layered approach successfully targeted US car crashes. For decades, motor-vehicle accidents were the most common cause of death among young people. But investments in research and the resulting evidence-based regulations put a major dent in those numbers. “It wasn’t one thing: we did seat belts, we did airbags, we did improvements to the roads,” says Rebecca Cunningham, a gun-violence researcher at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. “We got less drunk driving. It was all these layers of public-health protection on top of each other.”

Raising the legal age to drink from 18 to 21 helped to reduce the number of young drunk drivers. Cunningham sees a similar potential precedent for raising the legal age to buy a rifle.

But funding for gun-violence research has been a fraction of that invested in traffic safety — nearly fourfold fewer dollars per life lost. In 2020, gun violence surpassed car accidents as the leading cause of death among US children and young adults.

“For 20 years, we turned our back on the health problem and declined to do research on it,” Wintemute says. “How many thousands of people are dead today who would be alive if that research had been allowed to continue?”

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on July 1 2022.