Editor’s Note (5/12/22): This story was updated when the White House announced one million COVID deaths in the U.S.

Laura Jackson feels the loss of her husband Charlie like she is missing a part of herself. He died of COVID early in the pandemic, on May 17, 2020, just weeks after the couple celebrated his 50th birthday. Charlie was an Army veteran who served in Iraq during Desert Storm, and Laura finds herself returning to images of war and loss—to those who have lost a limb but still feel its phantom tingle, who unthinkingly reach for a glass of water or try to step out of bed before realizing what has been lost forever. Even now she still turns to find Charlie, eager to share a joy or a disappointment, only to remember with a jolt that there is a missing space where he once was.

“I don’t know that you ever get over it,” says Jackson, who lives in Charlotte, N.C. “Your person who was supposed to be there for life—to have that tragically ripped away has been a huge, huge adjustment to make.”

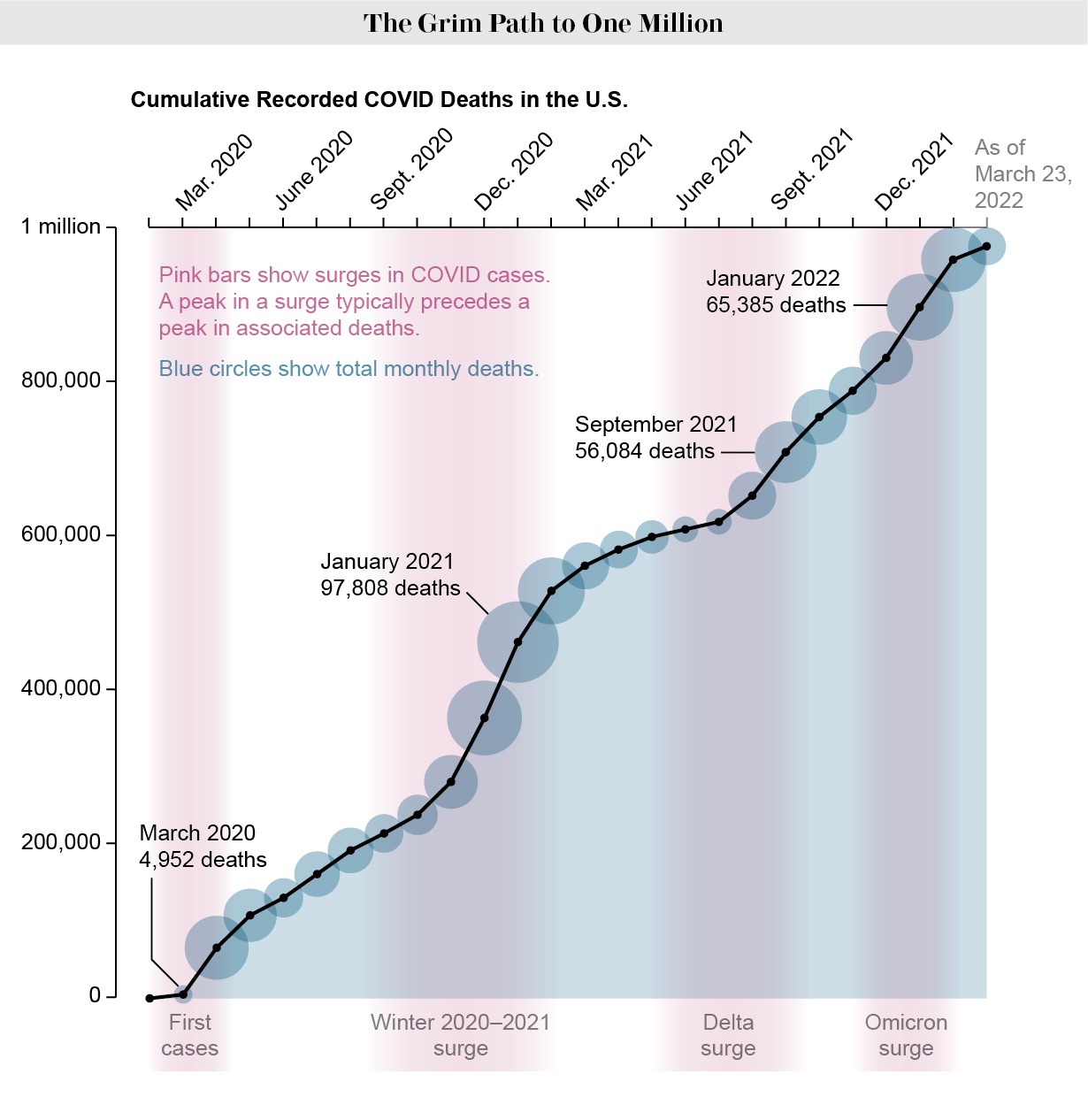

As of May 12, the U.S. has now officially recorded one million confirmed deaths from COVID. This toll is likely an undercount because there are more than 200,000 other excess deaths that go beyond typical mortality rates, caused in part by lingering effects of the disease and the strain of the pandemic. These immense losses are shaping our country—how we live, work and love, how we play and pray and learn and grow.

“We will see the rippling effects of the pandemic on our society and the way it impacts individuals for generations,” says Nyesha Black, director of demographic research at the University of Alabama. “This is definitely a huge marker in the way we will think about society moving forward—it will be that anchor event.” COVID has become the third leading cause of death in the U.S., after heart disease and cancer.

These deaths have wide-ranging consequences. The effects on children may be the longest-lasting. In the U.S., an estimated 243,000 children have lost a caregiver to COVID—including 194,000 who lost one or both parents—and the psychological and economic aftershocks can have lifetime negative impacts on their education and career.

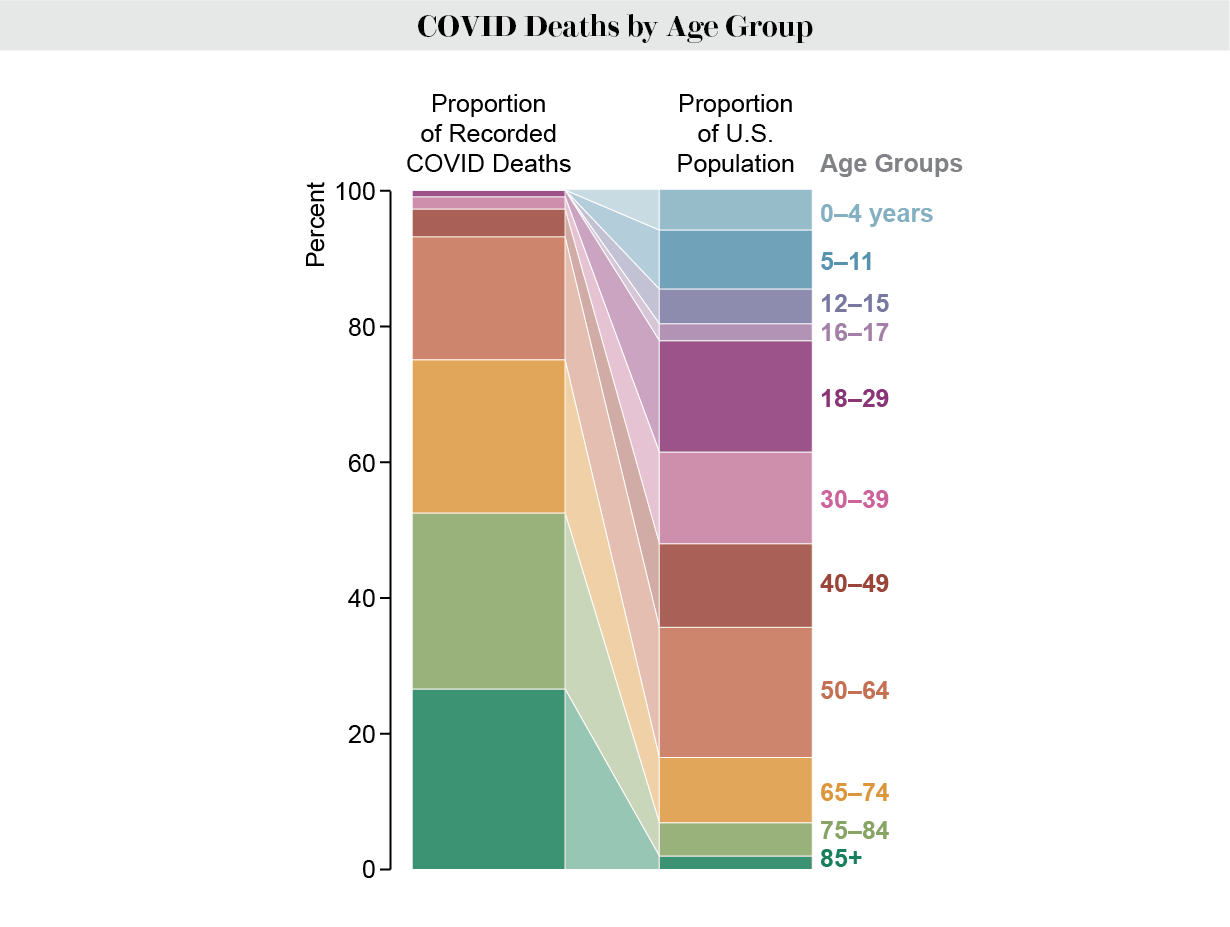

Certain communities have been hit especially hard, with older Americans and people of color suffering disproportionately. As of March 25, about three quarters of the dead, or around 730,000, have been people 65 and older. Many of them were otherwise healthy and, statistically, would have lived many more years, says Jennifer Dowd, a demographer at the University of Oxford. Their passing leaves a giant hole, she notes. “We’re probably not accounting for all the ways in which we rely on that age group to contribute to society,” from caring for grandkids to providing stable intergenerational family structures, Dowd says. On average, every death from COVID leaves nine people grieving.

In the U.S., there were 54.1 million people 65 and older in 2019, and since then the coronavirus has killed one out of every 74 of them. These deaths are more concentrated in even older populations: more than a quarter have occurred in those age 85 and older, while another quarter have been in those 75 to 84.

Younger people have not escaped. About 240,000 Americans between the ages of 18 and 64 have died, nearly a quarter of the total toll. Among working-age Americans, “we are seeing right now the highest death rates we have ever seen in the history of this business,” said J. Scott Davison, CEO of the insurance company OneAmerica, in late December 2021. “Death rates are up 40 percent over what they were pre-pandemic.” For comparison, he said, “a one-in-200-year catastrophe” would lead to a 10 percent increase, “so 40 percent is just unheard of.”

“People are dying in the prime of life,” says Andrew Stokes, an assistant professor of global health at the Boston University School of Public Health. “They’re leaving families. They were caregivers. When we think about the children left behind, the single moms and single dads who don’t have a partner any longer, that’s going to create inequity that will be experienced for years to come.” Those lost took others to the doctor or checked in on friends or neighbors to make sure they were eating well and their blood pressure or sugar levels were okay. “What does it mean when these ties have been broken?” Black asks. “Can you put these pieces back together?”

And certain types of work were hit harder by COVID than others. Those in fields such as food and agriculture, warehouse operations and manufacturing, and transportation and construction saw higher rates of death than in many other occupations. And working in a nursing home has been one of the deadliest jobs in the U.S.

“A lot of us demographers have just been tallying the losses, and it kind of snuck up on us—the scale of it all,” Dowd says. “We never thought it would keep going like this.” Such devastation has not been seen since World War II, when about 418,000 Americans died, she says. “We’re going to be trying to understand those long-term effects on health and mortality for a long time.”

Economic and Emotional Costs

Even as Laura Jackson navigated her grief, she was immediately faced with the financial repercussions of her husband’s death. A small insurance policy barely covered his funeral, and then she was on her own. “It has thrown my life in a tailspin,” she says. “Just in a matter of days, watching everything that we had, everything that he was maintaining, just pretty much go up in flames.”

After Charlie died, Jackson started getting home foreclosure and overdue bill notices. She relied on her three children, all in their 20s, for support until she could start a new job two months later. “It was a few months of stretching every dollar, trying to figure out how to balance things,” she says. Seven months passed before Jackson began receiving disability benefits on her husband’s behalf, and she still does not receive the full amount, she says.

“In certain communities or certain economic groups, there is not a lot of room for error,” Black says. “You don’t have the safety net in terms of the economic resources if you lost someone, and they were a contribution to the household. So those disruptions can be more long-term, or the effect of them can be more detrimental.”

Not all of these resources are part of the official economy. “A lot of communities that are lower-income, for example, they may not go to the private market to purchase childcare,” Black says. “So what happens when you don’t have your grandmother around or your mother around? Who can now watch your child?” Losing childcare can affects parents’ ability to work, making it more difficult to provide for their families. More than one million women left the workforce during the pandemic, in large part because of childcare disruptions.

A lot of that childcare came from grandparents, who play an integral role in children’s lives, providing emotional and financial support. More than 80 percent of Americans age 65 or older are grandparents, and about one in five provide childcare regularly, according to a 2015 Pew Research Center survey. In 2019 grandparents provided housing for 4.5 million children, Grandparents of color are more likely to help financially and logistically. According to a survey reported in 2012, more than half of Hispanic or Latino grandparents said they provided childcare for five years or more, and African American grandparents were most likely to be their grandchildren’s primary caregivers, compared with other groups—making the disproportionate losses from COVID in communities of color even greater.

After a primary caregiver’s death, kids often have a higher risk of many problems. More than half of kids report having significant mental health issues. Losses also put children at greater risk for physical, emotional and sexual violence, poverty, suicide, teen pregnancy, and infectious and chronic illnesses. Losing a caregiver can worsen feelings of abandonment, affect self-esteem and make it harder to cope with stress. The difficulties extend to kids’ education. Children who lose a parent tend to see their performance at school suffer, and that, in turn, harms future income and family stability. “In social epidemiology, we think about these effects as the long arm of childhood trauma—effects that exert themselves throughout the life course,” Stokes says. “It’s kind of a direct path from education to economic viability and security or having more precarious employments.”

For children, the aged and the rest of society, experts expect to see a long-term worsening trajectory of health and survival in coming years. One reason is the effect of “long COVID,” a cluster of debilitating symptoms, including fatigue, headache, pain and shortness of breath, that can last for months after an initial infection. The syndrome may also result in increased mortality, with people dying months after contacting the virus. Delays in getting health care, created by the crush of acute and long COVID patients during the pandemic, may lead to higher death rates for people who have developed diabetes, cardiovascular disease and other conditions. The U.S. already had a crisis of chronic disease, especially in working-age people, which is one reason why the coronavirus wreaked havoc, Stokes adds. “There’s an interaction with these chronic diseases, and it’s increasing the mortality risk from those conditions.”

Feeling Forgotten

When Kristin Urquiza’s father died of COVID at age 65 in June 2020, it changed her world. She took a leave from her job to grapple with her grief and trauma. The 40-year-old woman, who hails from Arizona but lives in San Francisco, was also filled with anger about what she saw as the pandemic’s mismanagement by then president Donald Trump and Arizona Governor Doug Ducey. These complicated feelings led Urquiza to co-found a survivor’s group called Marked by COVID, which now counts 100,000 members nationwide. Marked by COVID’s intention is to ensure these losses are not forgotten by society. Members are pushing for a national COVID memorial day and a 9/11-style commission to investigate the nation’s response to the pandemic.

“I wish, in some way, people could really see with pure visibility how many people are wearing the weight of this pandemic,” Urquiza says. Sometimes she imagines what would happen if people showed visible reminders of the effects of the pandemic—if the faces of everyone mourning a loss or suffering long-term symptoms shone in vivid color, pink or purple or red. “I think it would help bring home just how not normal these times are and how many people are suffering,” Urquiza adds.

These losses are particularly hard because many people did not have a chance to say goodbye in person or mourn with others; the risk of infection was too dangerous. “We didn’t get to grieve as we would do traditionally,” says Jackson, who is a member of Marked by COVID. This problem is made worse by survivors’ sense that a large number of Americans do not want to acknowledge the horrifying toll or learn from it moving forward. Instead people and pundits proclaim that they are “done with COVID.”

Urquiza does not want the country to wallow in grief. Rather she wants the U.S. to use the emotion to galvanize action. “This is a major disrupting event, and it gives us the opportunity to think about how we actually want to rebuild,” she says. “We’re a country that’s so deeply divided. I believe we can start to see one another as Americans and humans if we can hold space for what we’ve been through in this moment.”