The oldest battle on Earth, the one between bacteria and the viruses that prey on them, has been running for billions of years. It plays out in your gut, in soil, in every pond and puddle. And now, thanks to experiments aboard the International Space Station, scientists know it plays out differently when gravity disappears.

A study published in PLOS Biology sent the bacteriophage T7 and its favorite target, Escherichia coli, into orbit to watch what happens when the rules change. Bacteriophages, or phages for short, are viruses that infect and kill bacteria. On Earth, phage and host wage a relentless arms race: bacteria evolve defenses, phages evolve countermeasures, and the cycle repeats at furious speed. T7 can infect and destroy E. coli in under 30 minutes under normal conditions. But in microgravity, the researchers found, that timeline stretches dramatically.

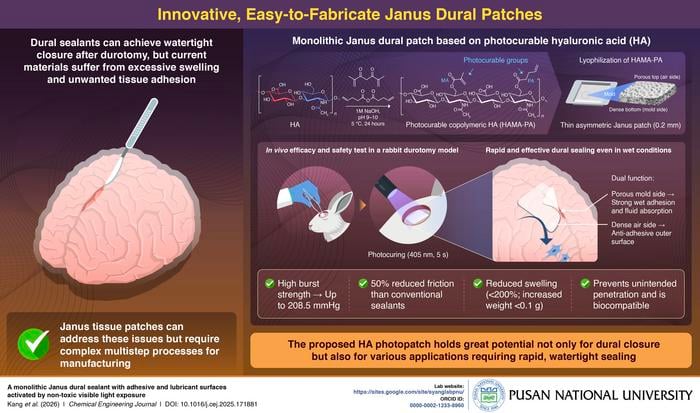

The reason is surprisingly physical. Without gravity, there’s no convection, no settling, no gentle stirring of particles through fluid. Phages and bacteria meet each other only through slow, restricted diffusion. In Earth-based controls, viral numbers exploded between two and four hours. In the space samples, nothing happened at those early time points. Yet by 23 days, the phages had succeeded. Microgravity slowed the attack but did not stop it.

Different pressures, different mutations

What made the study genuinely surprising came from sequencing the survivors. After more than three weeks, both phages and bacteria had accumulated new mutations, and those mutations looked nothing like what appeared in the Earth controls. The space-faring phages developed changes in tail proteins that help them latch onto bacterial surfaces. The bacteria, meanwhile, evolved alterations in genes tied to their outer membranes and stress responses, the classic defensive playbook of a cell trying to keep viruses out.

The researchers then did something clever. They used a technique called deep mutational scanning to test 1,660 variants of the phage’s receptor binding protein, the molecular tool it uses to grab onto bacteria. The variants that thrived in microgravity looked completely different from those that thrived on Earth. Whatever selective pressure microgravity exerts, it rewards a different set of genetic solutions.

Turning space lessons into medicine

Here is where the study shifts from curiosity to potential clinical value. The team took the mutations that succeeded in space and built new phage variants from them. They then tested these “microgravity-informed” phages against two strains of uropathogenic E. coli, the kind that cause stubborn urinary tract infections and resist the original T7. The space-derived variants worked. They infected and killed bacteria that shrugged off the wild-type virus.

“Microgravity selections revealed novel genetic determinants of fitness and enabled efficient navigation of sequence space to find improved phage variants.”

The researchers are careful not to oversell. ISS experiments come with unavoidable limitations: freeze-thaw cycles, processing delays, fewer time points than anyone would like. And they disclose that some authors hold equity in a phage therapeutics company, a reminder that the path from orbit to pharmacy involves commercial interests.

Still, the broader point stands. Phage therapy, the use of viruses to kill drug-resistant bacteria, has been hampered by the difficulty of engineering phages that can hit new targets. This study suggests that microgravity acts like a different laboratory, one that exposes mutational possibilities hidden under Earth’s constant pull. For anyone worried about antibiotic resistance, that is a useful trick to have.

There is also a quieter lesson for long-duration spaceflight. Microbial communities aboard spacecraft are not simply Earth microbes in a new zip code. When the physics of mixing and transport change, the evolutionary pressures change too. Phage and bacteria can drift onto trajectories no ground experiment would predict. For astronauts spending months or years in orbit or beyond, understanding those shifts matters. The microscopic arms race continues in space. It just follows different rules.

PLOS Biology, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3003568

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!