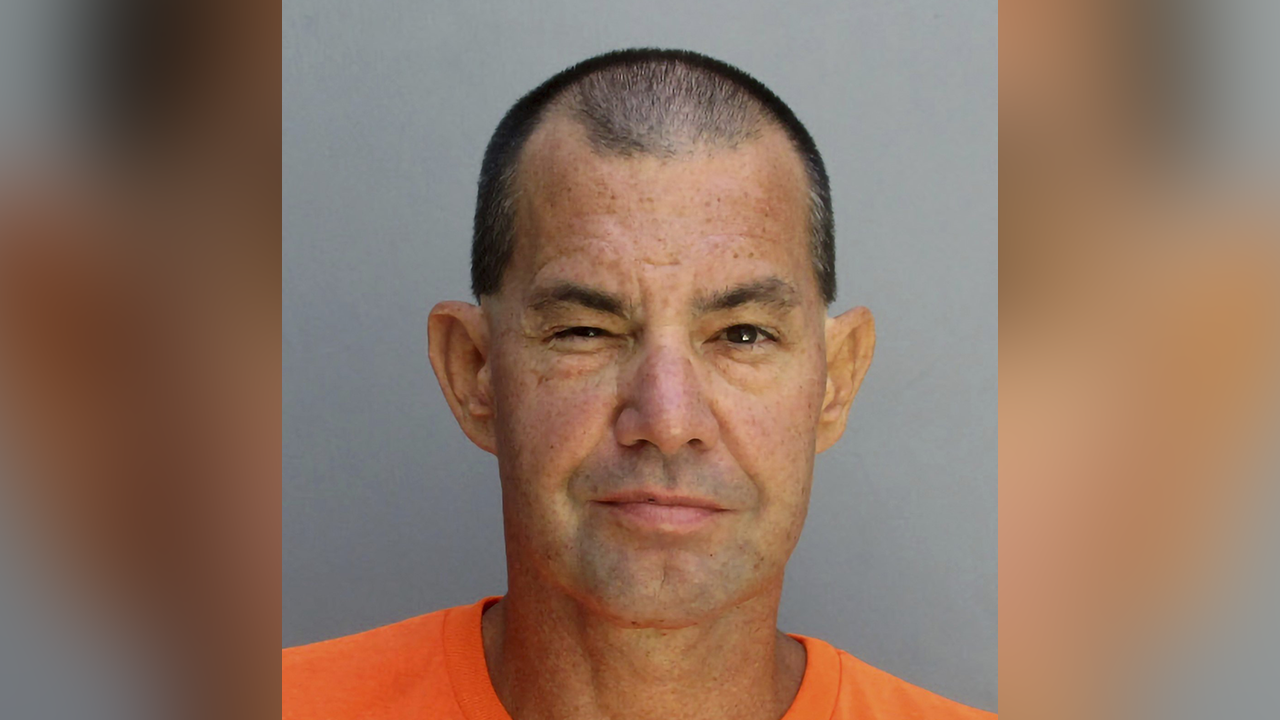

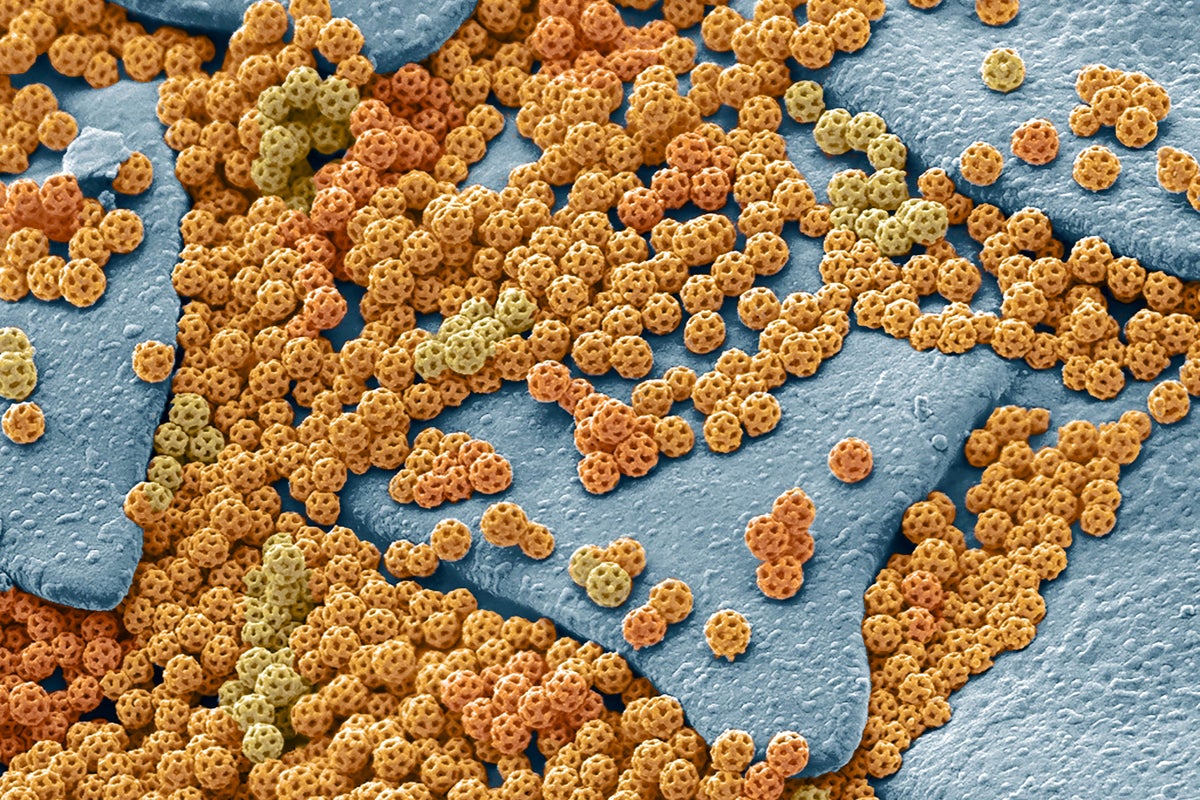

Many children’s toys contain hidden electronic components that can be recycled

Martin Smart/Alamy

Toys are a much larger contributor to electronic waste than vapes, according to an analysis by the United Nations.

In advance of International E-Waste Day on 14 October, the Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Forum collaborated with the United Nations Institute for Training and Research to quantify how much electronic waste the world disposes of without realising it has the potential to be recycled.

In all, 9 billion kilograms of so-called “invisible” e-waste is thrown away every year, worth nearly $10 billion, according to the analysis. Around one-third of this waste comes from children’s toys containing hidden electronics, some 3.2 billion kilograms. Toys contribute 77 times more to the world’s invisible e-waste than vapes, which account for 42 million kilograms a year. The UN estimates that 844 million vapes are thrown away every year.

“Electronic waste is our fastest growing waste stream,” says Oliver Franklin-Wallis, the author of Wasteland, a book on waste disposal. “It’s also by far our most valuable waste stream, when it comes to household waste.”

However, very few people seem to realise that many common items they dispose of contain e-waste. Highlighting that was the purpose of the research, says Magdalena Charytanowicz at the WEEE Forum. “We’re trying to make people understand that the items they may not suspect are electronics actually do contain a lot of precious materials, like copper and rare earth [elements],” she says.

Globally, just 17 per cent of e-waste is collected and recycled, although in some areas that is far higher. Across the European Union, around 55 per cent of electronic waste is officially collected and reported.

People recognise that vapes are electronic waste because of the very obvious battery that powers them, says Louise Grantham at REPIC, a UK-based WEEE compliance scheme. “Getting that association with toys I suspect is probably more difficult because it might be a big toy powered by a small battery,” she says.

That is supported by research by a Swiss member of the WEEE Forum, says Charytanowicz, which found that if the electronic function wasn’t the primary function of a device, users didn’t consider it as electronic.

Franklin-Wallis says overlooking the contribution toys make towards electronic waste is a risk. “Anyone with small children knows just how much of this stuff is in every household now,” he says, calling it a “tremendously rich source” for waste processors and the wider economy.

However, collecting that waste is easier said than done – particularly given the current state of recycling infrastructure, according to Franklin-Wallis. “The collection of electronic waste in [the UK] is relatively poor,” he says. “I think there’s still a job yet to be done in informing the public on the value of the materials, how to dispose of them and recycle them safely.”

One way to tackle that, says Charytanowicz, would be to implement a UN treaty that regulates the recycling of e-waste at a global level – similar to one that binds countries to recycling plastics.

Topics: