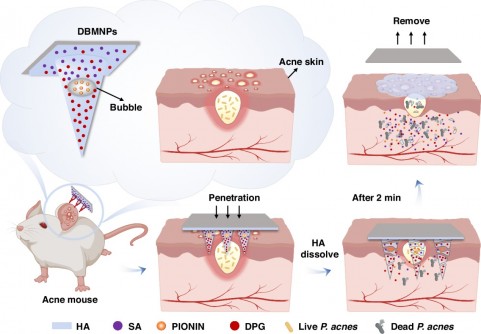

THE MICRONEEDLES dissolve within minutes, but not before they’ve done something conventional acne treatments struggle with: deliver three entirely different drugs exactly where they’re needed. One drug floats in water. Another repels it. The third sits somewhere between. For decades, that incompatibility has frustrated dermatologists trying to treat the 85 per cent of teenagers who develop acne. Now, researchers at Tsinghua University’s Shenzhen campus have embedded microscopic bubbles inside biodegradable needles to solve the problem.

Can Yang Zhang and colleagues didn’t set out to revolutionise transdermal drug delivery. They were wrestling with a more prosaic challenge: how do you load drugs with wildly different solubilities into the same patch without them crystallising, separating, or simply refusing to play nicely together? The answer came from an unexpected direction. Hollow bubble structures that create distinct compartments within each needle.

The team fabricated patches from hyaluronic acid, a sugar molecule already used in cosmetics and joint injections, mixing two molecular weights to get the right balance of strength and flexibility. Each patch contains 100 needles arranged in a 10-by-10 grid, standing about half a millimetre tall, just enough to pierce the skin’s outer barrier without hitting nerve endings. Under the microscope, the architecture reveals itself: bubbles roughly 176 micrometres across, with walls about 10 micrometres thick, suspended within the needle like tiny balloons frozen in ice.

Inside this structure, three drugs occupy separate real estate. The main body of each needle holds dipotassium glycyrrhizinate, a hydrophilic anti-inflammatory compound derived from liquorice root that dissolves readily in water. The bubble walls themselves contain PIONIN, a hydrophobic antibacterial agent that prefers oily environments and targets Propionibacterium acnes (the bacterium that thrives in blocked hair follicles and drives inflammation). The base layer carries salicylic acid, which helps shed dead skin cells and prevent pore blockages.

Confocal microscopy images, captured in successive 50-micrometre slices through the needle’s depth, confirm this spatial segregation. Fluorescent dyes standing in for each drug light up in their designated zones: red in the main body, green in the bubble regions, blue at the base. The separation isn’t merely aesthetic; it dictates when and how fast each drug reaches the skin.

When Zhang’s team tested the patches on porcine cadaver skin, the needles consistently penetrated about 350 micrometres deep, reaching well into the dermis where acne lesions develop. The needles bent slightly under pressure but didn’t break, withstanding an average force of around 4.7 megapascals, more than sufficient for reliable insertion. Once inserted, the hyaluronic acid began absorbing moisture from the tissue, and the needles dissolved almost completely within two minutes.

Release profiles for the three drugs followed distinct patterns that matched their therapeutic roles. Salicylic acid burst out first, with over half its payload released in 30 minutes and 95 per cent gone within six hours, perfect for its job of quickly opening pores and reducing surface inflammation. Dipotassium glycyrrhizinate followed near-zero-order kinetics for the first four hours, maintaining steady anti-inflammatory action, with about 70 per cent released by the six-hour mark. PIONIN, trapped in those bubble walls, released most slowly of all, achieving roughly 50 per cent cumulative release at six hours as the hydrophobic compartments gradually broke down.

The real test came in mice. Researchers injected P. acnes bacteria into mouse ears to create acne-like lesions, then divided the animals into groups receiving different treatments: drug-free patches, topical drug solutions, or the full bubble-loaded patches. After three days of once-daily treatment, the differences were stark. Mice treated with bubble microneedles showed dramatically reduced ear swelling, nearly complete elimination of bacteria, and substantially lower levels of IL-6 (a pro-inflammatory signalling molecule), alongside increased IL-10, which dampens inflammation.

Tissue samples told an even clearer story. Ear sections from untreated mice were infiltrated with inflammatory cells, their tissue architecture disrupted by the infection. Mice that received topical drug solutions fared little better. The drugs simply couldn’t penetrate deep enough through intact skin to reach the bacteria-rich pustular regions. But tissue from bubble-microneedle-treated mice looked almost normal, with minimal inflammatory infiltration and preserved structural integrity.

The study’s corresponding author points to a fundamental formulation challenge that’s plagued acne therapy for years. Current treatments typically rely on either water-soluble or oil-soluble active ingredients, but rarely both, because combining them in conventional creams or gels often leads to phase separation or chemical incompatibility. Some researchers have tried creating soluble salts through acid-base reactions to enhance drug loading, but that approach only works for ionisable compounds and risks precipitation once the drugs enter the body’s physiological environment.

Bubble microneedles sidestep this entirely by creating physical separation rather than chemical compromise. The hollow structures provide dedicated loading space for hydrophobic agents without requiring organic solvents or chemical modification. And because the entire system is made from hyaluronic acid (a material already approved for various medical uses), the patches leave no sharp waste behind and dissolve completely within the tissue, avoiding the cross-contamination risks associated with reusable devices.

What makes this particularly promising for real-world use is the manufacturing simplicity. The team used standard polymer casting techniques with polydimethylsiloxane moulds, vacuum-assisted filling to create the bubble structures, and room-temperature drying. No specialised equipment, no high-temperature processing that might degrade sensitive drug molecules. The materials themselves are inexpensive: hyaluronic acid powder, basic drug compounds, and ethanol for the hydrophobic agent.

Beyond acne, Zhang’s group sees potential in other inflammatory skin conditions that might benefit from simultaneous delivery of incompatible drugs. Psoriasis treatments, for instance, often require both anti-inflammatory steroids and vitamin D analogues with different solubility profiles. Fungal infections might be treated with combinations of hydrophilic and hydrophobic antifungals. Even wound healing could be enhanced by co-delivering growth factors (hydrophilic) and antimicrobial peptides (often hydrophobic).

The technology isn’t ready for commercial rollout just yet. The team acknowledges they need to improve bubble uniformity to ensure consistent drug loading across all 100 needles in each patch. Scaling up production while maintaining quality control will require additional process optimisation. And while mouse studies are encouraging, human skin is thicker and more heterogeneous, which might affect both insertion depth and dissolution kinetics.

Still, for the millions of people who struggle with acne severe enough to require combination therapy but mild enough that oral antibiotics seem like overkill, these bubble-embedded patches offer something that’s been lacking: a way to apply multiple incompatible drugs exactly where they’re needed, with controlled release profiles and no pills to remember.

The research appears in Microsystems & Nanoengineering, part of a growing body of work reimagining how we think about getting drugs through the skin barrier. As microneedle technology matures and moves toward clinical trials, we’re likely to see more creative solutions to the fundamental formulation challenges that have constrained transdermal delivery for so long. Sometimes the answer to complex pharmaceutical problems isn’t better chemistry. It’s better architecture.

Study link: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41378-025-01079-y

Related

Discover more from SciChi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.