CLIMATEWIRE | Industrialized communities in the Deep South are the most vulnerable in the U.S. to climate change, according to a new index created by the Environmental Defense Fund and Texas A&M University that analyzes climate impacts and neighborhood conditions such as poverty and health.

Almost all of the most vulnerable communities are located along the Gulf Coast from Mobile, Ala., to Corpus Christi, Texas — a flood- and hurricane-prone region with deep pockets of poverty, poor health and economic and racial inequities. Communities in Memphis, Tenn., Birmingham, Ala., and Chattanooga, Tenn., also scored high on the index.

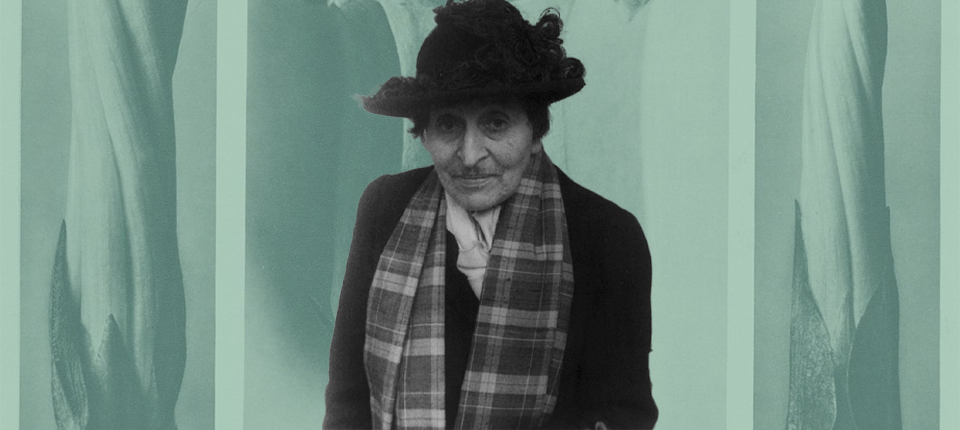

“Black communities in the Deep South are in the fight of their lives to protect their community from years of environmental racism, and we need every tool available to showcase what years of pollution look like in our communities,” said Beverly Wright, founder and executive director of the New Orleans-based Deep South Center for Environmental Justice.

Wright applauded the new index, saying in an email that the “data is pivotal to ensuring those federal resources reach the communities they are intended to.”

The index is the latest in a series of new or newly updated interactive tools that rate environmental and climate risks in more than 70,000 small geographic areas known as census tracts, each with just a few thousand residents. The effort comes as the Biden administration is prioritizing “disadvantaged communities” in allocating billions of dollars in new environmental and community-building spending.

The new index will help “ensure that adaptation efforts are targeted to those most in need,” Grace Tee Lewis, lead author and senior health scientist in EDF’s Climate and Health program, co-wrote in a blog post.

Other interactive tools include the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Environmental Justice Index, the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s National Risk Index of Natural Hazards and EPA’s EJScreen, launched in 2015 and updated in 2022. The White House recently published the Climate and Economic Justice Screening tool to help guide federal spending on climate and environmental protection under the Biden administration’s Justice40 Initiative.

More than a dozen states including California, New York and Pennsylvania have their own screening tools, which are sometimes used to prioritize funding and protect vulnerable areas.

And in August, Wright’s group and the Bullard Center for Environmental and Climate Justice at Texas Southern University launched the HBCU Climate and Environmental Justice Screening Tool as part of a collaboration with Justice40. The Justice40 initiative aims to allocate 40 percent of the benefits from federal investments in climate and clean energy to “disadvantaged communities,” which have high levels of environmental exposure and social vulnerability.

The index by EDF and Texas A&M stands out in its breadth and scope, officials said. Researchers collected data on more than 180 indicators of both “baseline vulnerabilities” and climate change risks — roughly three times the number of indicators that the White House used for its screening tool. The data cover five categories: health, socioeconomic status, infrastructure, environment and extreme events such as hurricanes.

The five categories are part of the climate-change index because “vulnerable groups will be disproportionately affected due to greater exposure to climate risks and lower ability to prepare, adapt, and recover from their effects,” the researchers wrote in the journal Environment International. Such communities have been the focus of “environmental justice” advocacy campaigns.

The index aims to help communities as they look into federal funding opportunities, including from the bipartisan infrastructure law and Inflation Reduction Act.

“The goal is to provide a science-based tool that provides the necessary evidence to support greater investment in these areas,” said Elena Craft, EDF’s associate vice president and expert on health and climate.

Sara Colangelo, director of Georgetown University’s Environmental Law & Justice Clinic, said the index will help vulnerable communities “both by offering data that confirm a community’s lived experience, and by visualizing risk to decisionmakers at the government, nonprofit and corporate levels.”

The index provides “a nuanced understanding of climate vulnerability,” Colangelo added.

The index shows the most climate-vulnerable communities are along the industrialized Gulf Coast from Corpus Christi to Mobile, as well parts of Memphis and St. John the Baptist Parish, La., along the Mississippi River. The parish south of Baton Rouge, La., is part of the region widely known as “cancer alley.” EPA is investigating the area’s legacy of industrial pollution and high cancer rates.

Some high-ranking areas outside the South include major cities such as Philadelphia, portions of the Ohio Valley and central and Southern California.

Weihsueh Chiu, a study co-author and professor in Texas A&M’s School of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, stressed the “hyperlocal nature” of health and socioeconomic disparities that will be magnified by rising average temperatures and associated disasters like hurricanes, wildfires and droughts.

“If you look at particular indicators, some are spread out geographically” across states and counties, Chiu said. “But many of them, especially those baseline vulnerabilities, you cross the street and it’s a different world kind of thing.”

Chiu said the South generally scores high on the index for baseline vulnerabilities because it has high rates of poverty and health problems. “It highlights a whole lot of the things the EJ movement has been talking about,” he said.

Reprinted from E&E News with permission from POLITICO, LLC. Copyright 2023. E&E News provides essential news for energy and environment professionals.