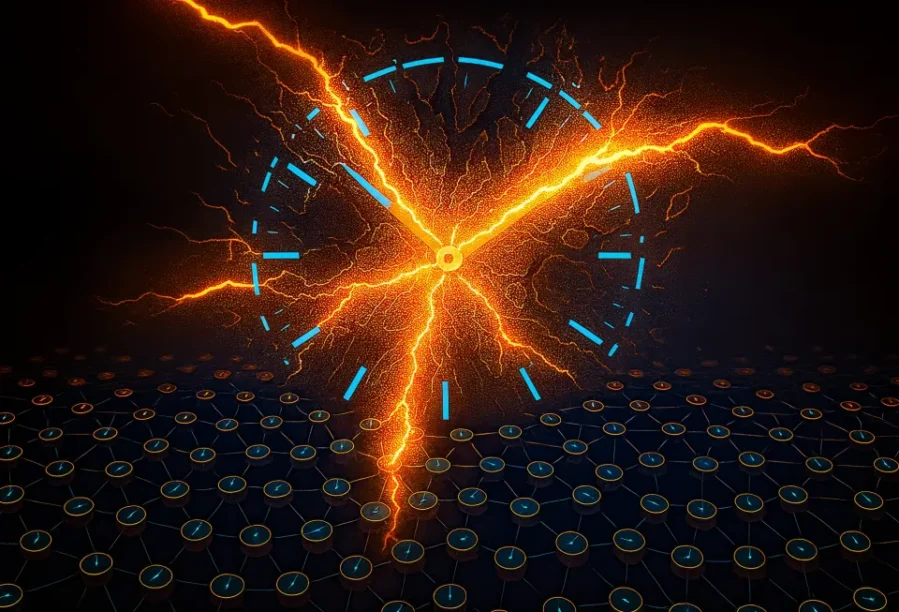

There’s a cruel irony at the heart of neuromorphic computing. Engineers build chips that mimic the brain’s architecture, billions of artificial neurons firing in efficient bursts, only to discover that the larger the system grows, the slower it becomes. The culprit? A synchronization mechanism that has nothing to do with how actual brains work.

The problem is rooted in physics. In conventional neuromorphic chips, a single timing signal has to reach every component. That signal travels at the speed of light, sure, but it still has to physically propagate across the chip. The delay scales with the square root of the number of neurons. Double your neuron count from one million to four million, and your synchronization overhead doesn’t just double, it increases by a factor of two. By the time you’re running systems with hundreds of millions of neurons, interconnected across multiple chips, you’re spending more time waiting for synchronization than actually computing. The whole system crawls at the pace of its most distant component.

Now a team at Yale, led by Professor Rajit Manohar, has published a solution in Nature Communications that sidesteps this limitation entirely. Their system, called NeuroScale, abandons the idea of a master clock. Instead, it lets neurons synchronize only with their immediate neighbors, the ones they’re actually connected to.

The Global Barrier Problem

Neuromorphic chips, custom integrated circuits that mimic how the brain works, are used to study brain computation and develop neuroscience-inspired artificial neural networks. Most large-scale systems, including IBM’s TrueNorth and Intel’s Loihi, use what’s called a global barrier. It’s essentially a synchronization checkpoint that forces every artificial neuron and synapse to pause and align before proceeding to the next computational step. This ensures deterministic results, you get the same output for the same input every time, which is non-negotiable for scientific applications and commercial deployment.

But the researchers note the fundamental limitation:

“A drawback of the current implementations of explicit time is that they either directly or indirectly rely on global synchronization, which limits the scalability of the overall system.”

The mathematics are unforgiving. In a two-dimensional chip layout, that synchronization signal must physically “touch” every neuron. The delay grows as O(√N), where N is the number of neurons. It’s not a software problem you can optimize away. It’s a hard physical constraint, like trying to simultaneously tap every person in a stadium on the shoulder when you can only move at a fixed speed. Real brains, of course, have no such limitation. They’re massively parallel and entirely asynchronous.

Distributed Time, Constant Speed

NeuroScale’s insight is deceptively simple: you don’t need every neuron in the system to be synchronized. You only need connected neurons to agree on their relative timing. If neuron A sends a spike to neuron B, those two need to be in sync. But neuron C, halfway across the chip and not connected to either, can be doing its own thing on its own schedule.

The system implements what the researchers call distributed, event-driven synchronization. Small clusters of connected neurons coordinate locally, but there’s no central timekeeper enforcing order across the entire network. The team emphasizes what this preserves:

“Custom integrated circuits modeling biological neural networks serve as tools for studying brain computation and platforms for exploring new architectures and learning rules of artificial neural networks.”

When the researchers simulated NeuroScale against TrueNorth and Loihi architectures, scaling up to 16,384 cores, the difference was dramatic. NeuroScale’s wall-clock time remained essentially flat, O(1) scaling. The global barrier systems saw their processing times climb along the expected O(√n) curve. At maximum scale, NeuroScale was more than four times faster. Even more impressive: when only a small fraction of the system was active, a common scenario in energy-efficient computing, NeuroScale maintained its performance. The conventional systems still paid the full synchronization cost.

The team verified determinism by running the same neural network on their hardware prototype, their hardware simulation, and a software reference model. The spike patterns matched exactly, neuron by neuron, time step by time step. That one-to-one correspondence is critical because it means algorithm designers can work at the software level without worrying about hardware non-determinism creeping into their results.

What does this enable in practical terms? At a billion neurons, you start approaching the scale of a bee’s brain. That’s enough to handle real-time sensory processing, autonomous navigation, and complex pattern recognition, all while sipping milliwatts instead of megawatts. The distributed architecture also means these systems could keep scaling: ten billion neurons, a hundred billion. The synchronization overhead simply doesn’t grow.

Lead author Congyang Li says they’re now moving to fabricate the actual NeuroScale chip, transitioning from simulation to silicon. They’re also exploring hybrid designs that blend NeuroScale’s distributed approach with elements from conventional neuromorphic systems. For the first time in the field’s history, the fundamental physics barrier to scaling brain-inspired chips may actually be surmountable.

Nature Communications: 10.1038/s41467-025-65268-z

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!