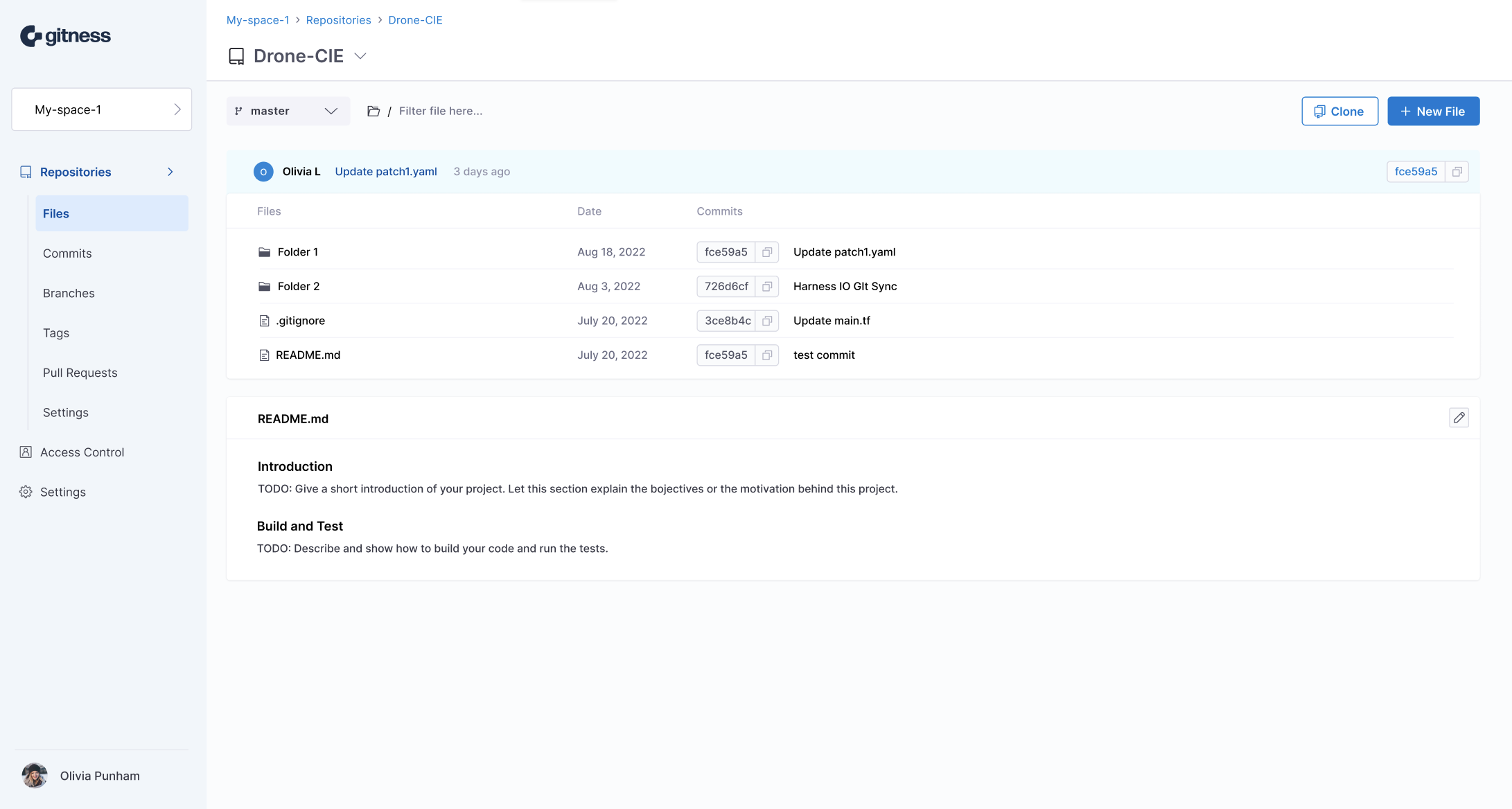

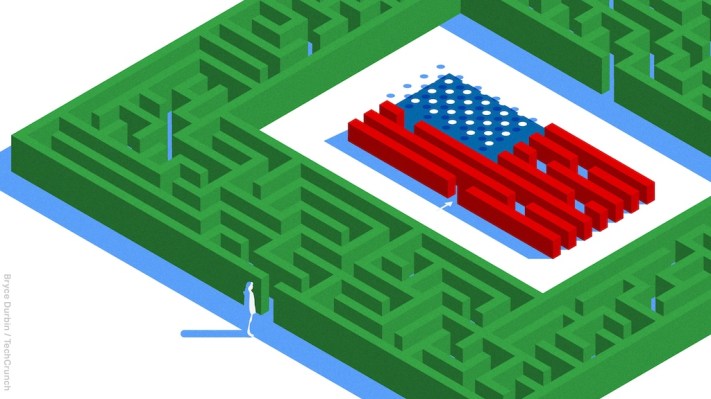

Climate change is the greatest threat humanity has ever faced, and the United States has begun mobilizing an army to fight it: the American Climate Corps. Formerly conceptualized as the Civilian Climate Corps, the new initiative will “put more than 20,000 young people on career pathways in the growing fields of clean energy, conservation and climate resilience,” the White House said in a statement announcing the launch Wednesday. That means civilian gigs like managing forests to prevent wildfires, preserving coastal wetlands to mitigate sea-level rise, and retrofitting buildings to be more energy efficient.

“We’re seeing just a tremendous sense of urgency from young people who want to get into the business of helping build that more sustainable future,” Ali Zaidi, the White House national climate adviser, tells WIRED. “Our goal is both to recruit from a diverse set of backgrounds—nobody left out, everybody welcome—but also to field a full team against the broad set of climate solutions that we know are available.”

The American Climate Corps is a rebirth of the Civilian Conservation Corps, or CCC, which put 3 million people to work during the Great Depression developing the national parks, building roads and trails, and managing forests. Now the idea is to prepare communities and the landscape for the ravages of climate change while creating jobs and stimulating local economies. “It’s nice to see the Biden administration acting to provide youth with opportunities to acquire training for 21st-century green jobs,” says environmental economist Mark Paul of Rutgers University. “And also to acquire an outlet to channel their frustration and anxiety regarding the current climate crisis plaguing the nation.”

The beauty of a national program, Paul says, is that it can be adapted to meet a community’s needs. Mountain towns, for instance, desperately need hands to clear the built-up dead vegetation that’s fueling ever-bigger wildfires. Coastal communities need help restoring seaside ecosystems that naturally absorb storm surges. Urban areas need people and funds to plant more trees, mitigating the “heat island effect,” in which the built environment traps the sun’s energy, making cities much hotter than rural areas.

There’s some reason to hope that the program can cut through partisan bickering and be embraced in red and blue districts: A poll released in 2020, conducted by Data for Progress and the Justice Collaborative Institute, found that 80 percent of Democrats and 74 percent of Republicans wanted the Civilian Conservation Corps to return. “Hurricanes don’t swerve based on whether a state is red or blue,” says Zaidi. “Wildfires don’t pick and choose based on who you voted for in the last election. So the climate crisis is showing up to all of our doorsteps.”

Like the CCC before it, the American Climate Corps aims to put people to work. (A sign-up form for interested workers is already online.) But while the CCC employed millions over about a decade, in its first year the Climate Corps plans to involve something more like 20,000. “Is it enough? Absolutely not. But I think that we can and should think of this as a crucial demonstration program,” says Paul. “My hope is that this program will be substantially scaled moving forward.”

The additional goal of the Climate Corps is decarbonization—which will in turn create more jobs by juicing the green economy, including the booming heat pump industry. One of the corps’ most important components is perhaps its least sexy: “implementing energy efficient solutions to cut energy bills for hardworking families.” That means installing better insulation and windows so it takes less energy to heat and cool buildings, and solar-powered heat pumps, which run without any fossil fuels. These will also go a long way in keeping down indoor temperatures during the summer. “Let’s remember that heat is actually the number one killer of Americans when it comes to climate-related disasters,” says Paul.

Many green jobs require skilled labor, which was already in short supply before last year’s Inflation Reduction Act got on track to create an estimated 1.5 million more of them. “We need to lower the barrier of entry for a broader set of Americans to be able to enter the clean energy workforce,” says Zaidi. “Our ambition is only limited at this point by our capacity to build and to deliver these solutions.”