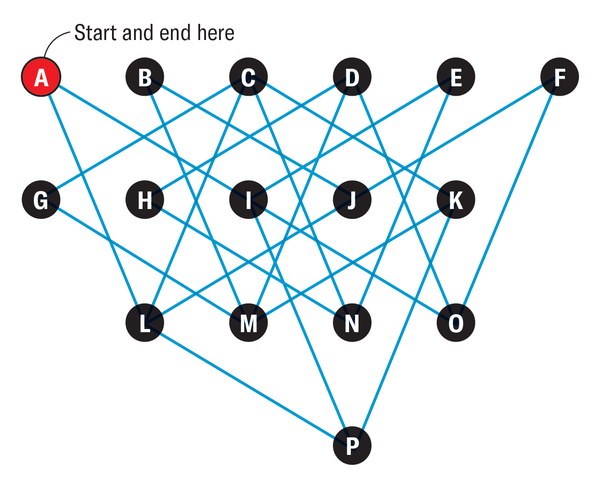

PICTURE a necklace stretching thousands of kilometres into space, each bead a computing node powered by continuous sunlight, working together to answer ChatGPT queries from users on the ground. It sounds like science fiction, but engineers at the University of Pennsylvania have designed a system that could make this vision surprisingly practical.

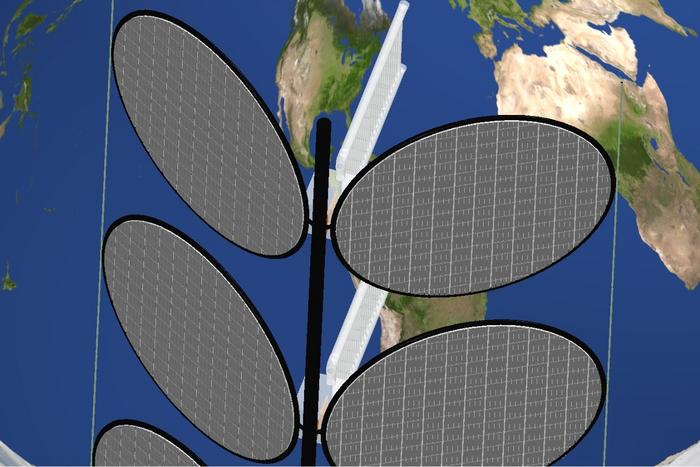

The design resembles a plant more than a satellite. Long vertical stems hold computing hardware whilst thin solar panels branch out like leaves, drinking in sunlight that never sets. The whole structure hangs in orbit, pulled taut by the competing forces of Earth’s gravity and the centrifuge-like effect of orbital motion. “Just as you can keep adding beads to form a longer necklace, you can scale the tethers by adding nodes,” says Igor Bargatin, the mechanical engineer who led the project.

We’ve reached an inflection point with artificial intelligence. Global data centre power consumption sits around 52 gigawatts currently and is expected to double by 2026, driven almost entirely by AI workloads. Most of that growth comes not from training new models but from running them—the billions of queries to systems like ChatGPT that we make every day. Each query demands electricity, and terrestrial power grids are already straining under the load. Several startups and governments have proposed moving data centres into space, where solar power flows continuously and cooling systems don’t compete for Earth’s water. Most designs have been either impractically small or impossibly complex, though.

Bargatin and his colleagues—including associate professor Jordan Raney and doctoral student Dengge Jin—think they’ve found the sweet spot. Their tethered design avoids the two main problems plaguing other space data center concepts. Swarm approaches, where millions of independent satellites each handle a fraction of the computing load, create nightmarish traffic management problems. “If you rely on constellations of individual satellites flying independently, you would need millions of them to make a real difference,” Bargatin says. Rigid structures assembled robotically in orbit, by contrast, could host substantial computing power but their size and complexity put them beyond current capabilities.

The Penn design sits neatly between these extremes. Each data centre consists of thousands of identical nodes linked along a vertical tether chain, aligned radially from Earth like beads on a string pulled straight by orbital forces. The same physics that’s kept tether systems stable in low Earth orbit for decades—including one that stretched 31.7 kilometres in 1996—would keep this chain taut and properly oriented. The longest chain they’ve modelled could stretch tens of kilometres and support up to 20 megawatts of computing power. Equivalent to a medium-sized terrestrial data centre.

What makes the design particularly clever is how it handles the eternal problem of space structures: keeping solar panels pointed at the Sun without constantly burning propellant. The team’s solution relies on something freely available in space—sunlight itself. By angling the solar panels slightly into a chevron configuration, incoming photons exert just enough pressure to act as a restoring force, much like wind orienting a weather vane. “We’re using sunlight not just as a power source, but as part of the control system,” says Bargatin. “Solar pressure is very small, but by using thin-film materials and slightly angling the panels toward the computer elements, we can leverage that pressure to keep the system pointed in the right direction.”

The orbit they’ve chosen helps too. Dawn-dusk sun-synchronous orbits, at roughly 1,600 kilometres altitude, remain in constant sunlight because the orbital plane precesses with Earth’s annual motion around the Sun. The satellite stays perpetually aligned with the terminator—that line dividing day from night on Earth’s surface below. No eclipses mean no batteries, no thermal cycling, and continuous power generation.

Each computing node would be modest by terrestrial standards—about 2 kilowatts of power driving perhaps two CPUs and several GPUs with high-bandwidth memory. Two thin-film solar panels, each 3 metres across and less than 100 micrometres thick, would generate the electricity. Water circulating through aluminium tubes would absorb waste heat from the processors and radiate it away through flat graphite-finned panels—the only way to shed heat in the vacuum of space, really. That same water loop provides a bonus: roughly 20 millimetres of liquid surrounding the electronics offers substantial shielding against ionising radiation, a major killer of space-based electronics.

Of course, thousands of computing nodes orbiting overhead are worth little if micrometeoroid impacts keep knocking them sideways. Raney and Jin used computer simulations to model impacts from debris travelling at 11 kilometres per second—the typical collision velocity in low Earth orbit. “It’s not a matter of preventing impacts,” Raney says. “The real question is how the system responds when they happen.”

The results were reassuring. When a 0.1-gram micrometeoroid—about half a millimetre across—strikes a solar panel’s outer edge, it sets off complex oscillations rippling through the chain. But those vibrations spread and dissipate naturally along the tether’s length. “It’s a bit like a wind chime,” says Raney. “If you disturb the structure, eventually the motion dies down naturally.” After an hour or two (sometimes less, depending on the mode), maximum angular deflections stabilise at around 0.3 degrees for a 101-node chain, or just 0.05 degrees for a 1,001-node chain. The chevron-shaped solar panels provide passive stabilisation that keeps oscillations centred around zero.

Redundancy provides additional resilience. Three tethers connect each node rather than one, so even a direct hit wouldn’t sever the chain. “Each node is supported by multiple tethers,” notes Raney. “So even if an impact severed a tether, the system would continue to function.”

The biggest limitation is latency. Round-trip light travel time to a satellite at 1,600 kilometres altitude adds only about 10 milliseconds—negligible for most applications. But training large AI models demands massive datasets transmitted continuously between computing nodes, which makes orbital training impractical with current technology. Inference, however, works beautifully. “Much of the growth in AI isn’t coming from training new models, but from running them over and over again,” says Bargatin. “If we can support that inference in space, it opens up a new path for scaling AI with less impact on Earth.” Model parameters, totalling perhaps 10 gigabytes, could be loaded before launch and updated occasionally.

Communication would rely on laser links between nodes and existing relay satellites like SpaceX’s Starlink constellation, which already provides the backbone bandwidth needed. A 20-megawatt orbital data centre devoted to AI inference would need at most 10 to 20 terabits per second of downlink capacity for user data—well within Starlink’s capabilities. For typical operations, requirements would be far lower, about 0.02 terabits per second per 2 megawatts, because user queries, responses, and screen shares compress efficiently.

Deployment would be straightforward compared to robotic assembly of rigid structures. Thousands of thin disk-shaped nodes could be stacked a few centimetres thick each, with the flexible tether coiled around them, all fitting inside a rocket fairing. Once in orbit, a small ion engine would gently tug the chain, unreeling nodes one by one like pulling beads through water. The same engines at each end could later perform orbit corrections and, eventually, controlled de-orbit when the hardware becomes obsolete after about five years.

The environmental argument is compelling. Launching a single 10-kilogram, 2-kilowatt node on a partly reusable Falcon 9 would produce about 630 kilograms of carbon dioxide emissions. Operating that same node on Earth for five years, assuming a typical natural gas grid, would produce roughly 40,000 kilograms of CO2—more than 60 times the launch emissions. A fully reusable future Starship would cut launch emissions roughly in half.

Bargatin envisions these systems eventually forming a belt around Earth. “Imagine a belt of these systems encircling the planet,” he says. “Instead of one massive data centre, you’d have many modular ones working together, powered continuously by sunlight.” Thousands of tethered data centres, each a vertical chain of computing nodes, could collectively deliver cloud computing and AI assistance worldwide without drawing on terrestrial power grids.

The team acknowledges substantial work remains, particularly on developing lightweight radiators capable of dissipating heat from sustained computing loads in space. But the core architecture relies on well-understood physics and tested technology. Tethers have flown in space since the 1960s. Thin-film solar cells exist. Commercial GPUs have survived ionising radiation doses far exceeding what they’d experience over a five-year mission. Laser communication between satellites is routine.

What’s new is putting these pieces together in a configuration that’s both ambitious enough to matter and simple enough to actually deploy. “This is the first design that prioritises passive orientation at this scale,” says Bargatin. “Because the design relies on tethers—an existing, well-studied technology—we can realistically think about scaling orbital data centres to the size needed to meaningfully reduce the energy and water demands of data centres on Earth.”

Whether we’ll actually see computing nodes hanging like beads on orbital necklaces remains uncertain. But as AI’s appetite for electricity continues growing, the appeal of power that never sets becomes harder to ignore.

Study link: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.09044

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!