Every Saturday, 13-year-old Caia Farrell goes running with her classmates. When the group passes a giant, idling truck, they cross the street to get away from the exhaust fumes. But it rarely helps.

“Outside my house right now, there are trucks moving back and forth to various construction sites, spewing pollution, idling on corners and polluting our air,” the Philadelphia-based seventh grader recently told EPA administrators during a public hearing.

That exhaust could be hurting Farrell and her classmates more than scientists previously understood. Researchers increasingly are finding a causal relationship between heavy-duty truck emissions and respiratory ailments such as asthma.

Rapid scientific advances also have allowed researchers to take a more granular look at where the majority of those toxic emissions are concentrated. The findings suggest an inequitable distribution, with low-income neighborhoods and communities of color bearing the brunt of toxic pollution.

EPA is trying to address these health impacts with a new rule to rein in emissions from buses, dump trucks and delivery vans. The standard has not been updated in over 20 years. But scientists say EPA’s regulatory analysis does not capture the full extent of just how bad the pollution is for some segments of the population.

Susan Anenberg is a professor at the George Washington University’s Milken Institute School of Public Health and serves on EPA’s influential Science Advisory Board. Anenberg said EPA’s regulatory impact analysis of its proposed clean truck rule, which the agency released in March, used a spatial resolution too coarse to capture neighborhood-scale impacts.

EPA’s analysis also did not include a demographic breakdown of the health benefits of the rule, she said.

“We need to be running the modeling at a higher spatial resolution,” Anenberg said. “This is not a knock against EPA. I’m just highlighting that there’s a gap in our technical capability right now to quantify the true benefits of this regulation.”

Those health benefits could be exponential. While heavy-duty trucks make up less than 10 percent of the U.S. vehicle fleet, they spew a disproportionate amount of harmful air pollution and planet-warming emissions.

Traffic-related air pollution is responsible for about 22,000 premature deaths in the United States every year. Of those deaths, 43 percent are attributable to on-road diesel vehicles. And the overwhelming majority of diesel vehicles in the country would be affected by EPA’s proposed rule.

The draft rule seeks to rein in nitrogen oxide emissions, which are precursors for harmful particulate matter and ozone. NOx emissions also produce a highly reactive gas called nitrogen dioxide, which is associated with the development of new cases of asthma among children.

A 2019 study published in The Lancet Planetary Health journal found NO2 was responsible for about 33 percent of new pediatric asthma cases in Los Angeles and New York City, and about 25 percent of cases in Washington.

EPA itself concluded in its 2016 Integrated Science Assessment that there “is likely to be a causal relationship” between long-term NO2 exposure and the development of respiratory ailments such as asthma.

However, health impacts from NO2 pollution were not taken into account in EPA’s truck rule analysis, Anenberg said.

EPA only calculates the monetized health benefits from reductions in particulate matter and ozone, EPA spokesperson Taylor Gillespie confirmed in an email.

Respiratory consequences are not felt evenly across the country. Black and Native Americans have the highest asthma rates compared to other races and ethnicities. In 2018, Black people in the United States were 42 percent more likely than white people to suffer from asthma, according to federal data.

In 2019, Black children died from asthma-related causes at eight times the rate of white children, according to figures from the Department of Health and Human Services. And Black children were five times more likely to be admitted to the hospital for asthma in 2017.

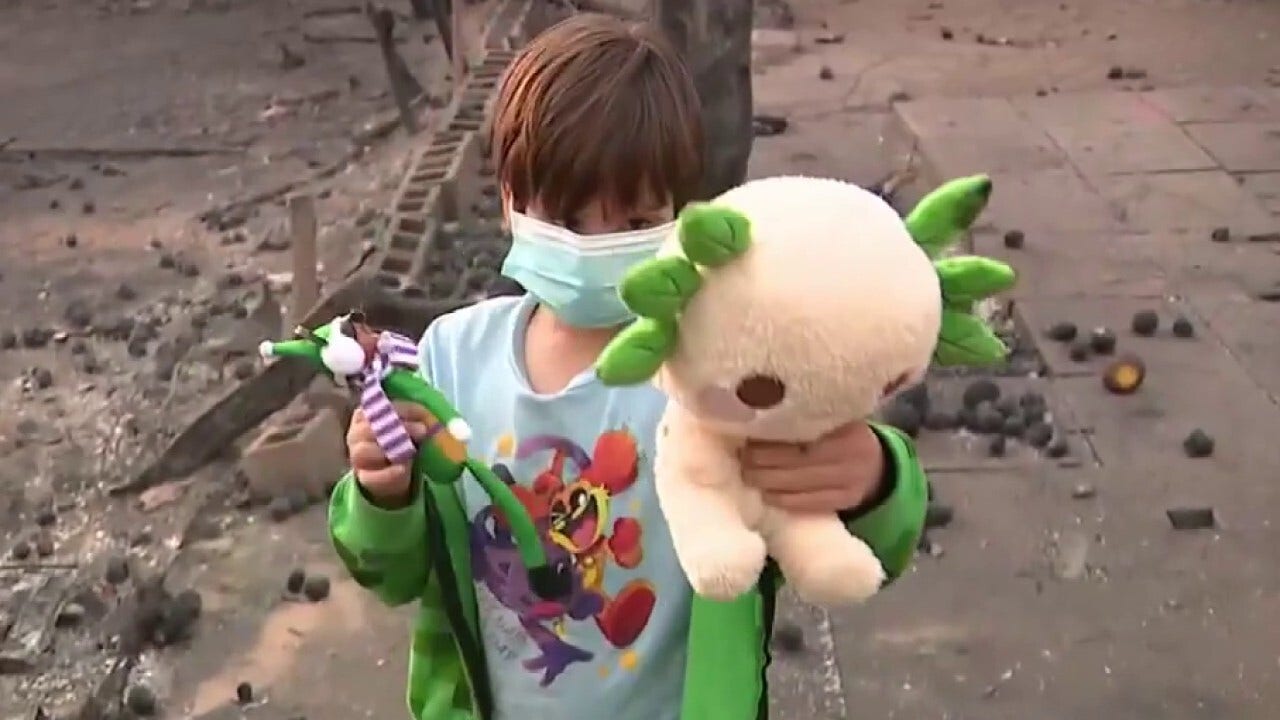

Jonathan Velasquez, 15, lives in a predominately Hispanic and Black neighborhood in Hyattsville, Md. He has suffered from asthma his whole life and says it can limit how much time he wants to spend outside.

“You can’t really do activities that most people do, like going outside to play sports,” he said. “It doesn’t feel good at all, and it makes everyone else worry about you and everything.”

Velasquez said he’s glad to see more electric and hybrid vehicles on the roads, but wishes the government would do more to help his community.

“There’s a lot of pollution, and there are people trying, but the government doesn’t seem to want to help too much,” he said.

The Biden administration has pledged to address environmental inequities in part by reining in toxic pollution from heavy-duty trucks. Those emissions disproportionately affect communities of color and low-income neighborhoods, which are more likely to be located near highways, freight corridors, rail yards and warehouses (Climatewire, May 16).

But there’s tension on how best to address the root of the problem. Environmental and public health groups have urged EPA to issue a truck rule in line with California’s recently enacted Heavy-Duty Omnibus program, which requires a 90 percent reduction in NOx emissions by 2027 compared to 2010 standards.

Truck and engine manufacturers, however, say that approach is technically and economically infeasible. They have advocated for a more gradual process.

EPA’s March proposal outlined two approaches. The first option mirrors California’s rule, but is not as strong. The second, less stringent option is more in line with what truck- and engine-makers have pushed for (Greenwire, March 8).

The agency also has faced criticism from state and local air agencies, who say without federal action to rein in emissions from trucks, it will be difficult for them to achieve federal air quality standards (Climatewire, May 26).

The National Association of Clean Air Agencies estimates that more than a third of the U.S. population lives in an area that does not meet federal air quality standards.

An EPA spokesperson recently said the March proposal is not a final regulation and noted that the rule is the first phase of the agency’s broader plan to address pollution from trucks.

In the meantime, Farrell said she and her friends have to take calculated risks about when to go outside.

“In Philadelphia, we frequently get alerts that our air is dangerous to breathe,” she said.

“On those days, I know it’s not safe for some of my friends to come out to the park or take a walk with me, because the bad air can trigger an asthma attack, which could lead to doctor or hospital visits, lots of medications, and missing school.”

Reprinted from E&E News with permission from POLITICO, LLC. Copyright 2022. E&E News provides essential news for energy and environment professionals.