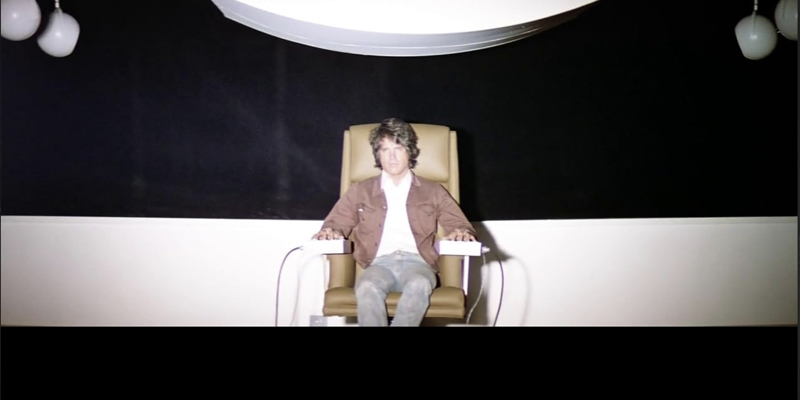

THE EXPERIMENTER tips an empty pitcher over two transparent cups, miming the familiar motion of pouring juice. Then she lifts one cup and pretends to pour its imaginary contents back into the pitcher. She slides the table forward and asks, “Where’s the juice?”

Kanzi, a 43-year-old bonobo watching from behind a screen, extends his finger and points: not to the cup that was just “emptied,” but to the one that should still contain pretend juice. He’s keeping track of something that doesn’t exist.

This isn’t just clever mimicry or a trained response. Kanzi appears to be doing something cognitive scientists have long considered uniquely human: forming what’s called a secondary representation. That’s the mental machinery that lets you hold two contradictory ideas simultaneously, knowing both cups are empty whilst tracking where the imaginary juice “is.” It’s the same cognitive kit that lets a child understand that a stick is really a stick but also, for the purposes of play, a sword. Without this ability, pretence collapses into confusion.

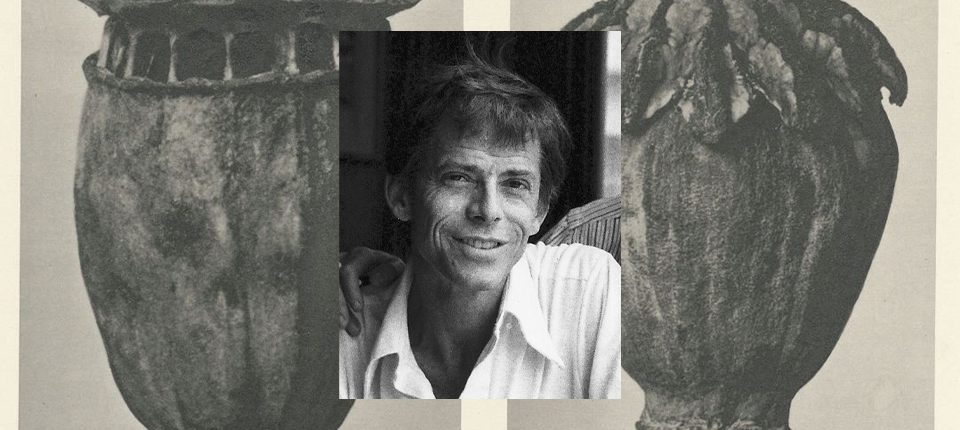

“Secondary representations enable our minds to depart from the here-and-now and generate imaginary, hypothetical, or alternate possibilities that are decoupled from reality,” write Amalia Bastos of Johns Hopkins University and Christopher Krupenye in their study published in Science. These representations underpin not just pretend play but also reasoning about possible futures, making causal inferences, and perhaps most significantly, tracking what others believe – even when those beliefs contradict reality.

The question of whether any nonhuman animal can form secondary representations has simmered in comparative cognition for decades. There’ve been anecdotes, sure. A juvenile chimpanzee observed dragging invisible blocks across the floor with the same posture he used for real wooden blocks. Female chimpanzees in the wild carrying sticks and cradling them like infants. A bonobo who appeared to eat blueberries off a photograph. But anecdotes are vulnerable. Maybe the chimp was just perseverating a rewarded motor pattern. Maybe the bonobo genuinely misperceived the photo as real fruit. Controlled experiments have been lacking.

Kanzi offered a rare opportunity. He’s what researchers call “enculturated”; raised in close contact with humans and trained since infancy to communicate using a lexigram board containing over 300 symbols. Crucially, he responds to verbal prompts, which meant Bastos and Krupenye could scaffold pretend interactions the way human caregivers do with toddlers. That verbal scaffolding is how children typically learn pretence in the first place.

The experiments followed a clever design. First, Kanzi breezed through training trials where he simply pointed to bottles containing real juice versus empty bottles, getting juice rewards when he chose correctly. He was perfect: 100 per cent across 18 trials. Then came the test, mixing those reinforced training trials with unreinforced probe trials at a 3:1 ratio. In probe trials, no reward, no feedback, just the pretend scenario and the question.

If Kanzi could only track reality, he should’ve chosen randomly between two cups he knew were empty. If he was simply drawn to whichever cup the experimenter handled most recently (a phenomenon called stimulus enhancement), he should’ve picked the wrong cup, since that one was “emptied” last. Instead, across 50 probe trials, Kanzi chose the cup containing “imaginary” juice 68 per cent of the time. He got it right on his very first probe trial.

But perhaps Kanzi wasn’t pretending at all. Perhaps he genuinely believed the pretend actions involved real juice. The researchers tested this directly in Experiment 2 by presenting two cups side by side: one empty, one containing actual juice. They pretend-poured into the empty cup and held the pitcher over the real juice without pouring. Then they asked, “Which one do you want?”

If Kanzi thought the pretend action created real juice, he should’ve been confused, choosing randomly between two options he believed both contained juice. Instead, he selected the real juice 77.8 per cent of the time. He could distinguish pretence from reality.

Experiment 3 replicated the findings with pretend grapes instead of pretend juice, and Kanzi succeeded again: 68.9 per cent correct across 45 trials, correct on the very first trial. Throughout all three experiments, something else remained steady: Kanzi’s motivation. In the reinforced training trials interspersed among probe trials, he maintained near-perfect performance (98.6 per cent and 99.3 per cent across experiments). He wasn’t frustrated by the unrewarded pretend trials. He wasn’t acting as though he’d been promised real juice and cheated. He seemed to understand the game.

The researchers systematically excluded alternative explanations. Kanzi couldn’t have learned the correct response through reinforcement because probe trials were never rewarded. He couldn’t have been imitating the experimenters because their pretend actions (pouring, emptying) were nothing like his response (pointing). Perceptual cues and stimulus enhancement predicted the opposite of what he did. The most parsimonious explanation is that Kanzi genuinely represented the pretend objects. That he formed secondary representations.

What remains uncertain is how much Kanzi’s enculturation mattered. Three possibilities present themselves. First, perhaps enculturated apes possess secondary representational abilities typical of their species, but their enhanced communication skills simply make these abilities easier for researchers to recognise experimentally. After all, there’s anecdotal evidence of pretence-like behaviour in wild apes too, and experimental evidence that apes track others’ false beliefs, another capacity requiring secondary representations.

Second, it’s possible that symbol training enhances existing capacities. If using lexigrams requires apes to concurrently represent both the physical symbol and its referent, perhaps routine lexigram use builds greater fluency with secondary representations. Then again, maybe lexigram training genuinely endows apes with a capacity they wouldn’t otherwise possess, fundamentally changing how their minds work.

Bastos and Krupenye favour the first two explanations, but testing between them will require experiments with both enculturated and non-enculturated apes. Violation-of-expectation paradigms that work with human infants might be adapted – for example, would apes be surprised if an actor pretend-poured juice into one cup but then drank from the other? Studies might also capitalise on naturally occurring putative pretence, like stick-carrying behaviour, to probe whether observers are surprised when the pretender stops treating the object maternally.

The implications ripple outward. If bonobos can form secondary representations, this capacity likely existed in our last common ancestor with great apes, which lived roughly 6 to 9 million years ago. That timeline pushes the cognitive foundations for imagination, future planning, and theory of mind much deeper into our evolutionary past than we’ve typically assumed.

Finding secondary representations in pretence contexts also strengthens the interpretation of other contentious research. Studies suggesting that apes track others’ beliefs have faced persistent scepticism; critics argue that apes might simply read behavioural cues like gaze direction to predict actions, without truly inferring mental states. But if bonobos demonstrably form secondary representations in one domain, it becomes more plausible that they deploy them in others. The cognitive machinery exists; the question becomes where it’s applied.

Similarly, research on ape planning has yielded unclear results about whether apes can hold multiple conflicting representations of possible futures in mind simultaneously: precisely the kind of cognitive juggling secondary representations enable. Kanzi’s performance suggests that at least some apes, under some conditions, possess this fundamental capacity.

This doesn’t mean all apes spontaneously engage in elaborate pretend play or constantly simulate alternative futures. Cognitive capacities don’t equal cognitive habits. But it does mean the potential is there, shaped by millions of years of evolution, waiting to be expressed under the right developmental or social circumstances. Kanzi, raised in a human-influenced environment with verbal scaffolding and symbolic communication, found a context where that potential could flower. Whether it would’ve emerged in his natural social world, we simply don’t know.

What we do know is this: the next time you see a child turning a banana into a telephone or fighting dragons with a stick, you’re watching a cognitive achievement with roots extending back to the Miocene epoch, when our ancestors and Kanzi’s still walked the same forests. The capacity to imagine what isn’t there, to decouple mind from world, may be older than we are.

Study link: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adz0743

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!

.jpg)