Stanford researchers have built a nanoscale optical device that entangles photons and electrons at room temperature, something quantum engineers have been trying to crack for years. The chip, described in Nature Communications, uses a patterned layer of molybdenum diselenide on top of silicon nanostructures to create stable qubits without the need for expensive cooling systems.

If it scales up, the approach could make quantum communication networks actually practical instead of just theoretically possible.

The Temperature Problem

Most quantum devices need to be cooled to near absolute zero, which means bulky cryogenic equipment and massive energy costs. At room temperature, electron spins typically fall apart in femtoseconds—far too fast to do anything useful with them.

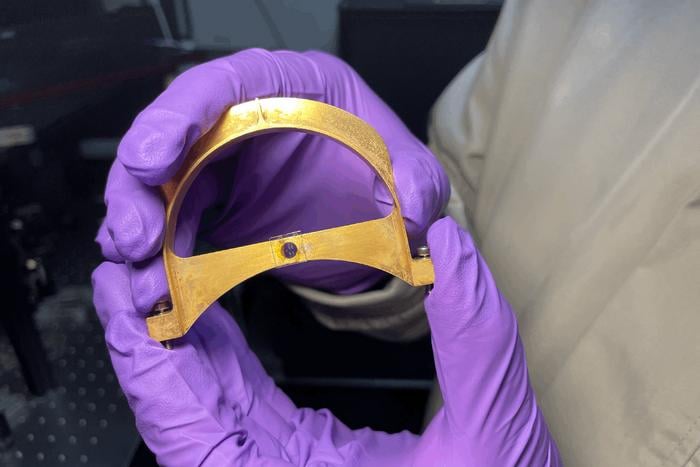

The Stanford team got around this by pairing an ultrathin layer of MoSe2 (a two-dimensional material) with a specially patterned silicon base. The silicon nanostructures guide photons into corkscrew paths, letting researchers control their spin direction with precision. When these “twisted” photons hit the MoSe2, they transfer their spin to electrons, creating coupled quantum states that stick around long enough to actually work with.

“The material in question is not really new, but the way we use it is,” said Jennifer Dionne, a professor of materials science and engineering who led the study.

The device integrates with standard silicon technology, which matters if you ever want to manufacture these at scale. The prototypes are tiny—about the size of a visible light wavelength—and invisible without magnification.

Spinning Photons, Stable Qubits

What makes the platform interesting isn’t just that it stabilizes quantum states at room temperature, but that it lets you manipulate them. By changing the geometry of the nanostructures, the team can steer photon spins up or down and reliably entangle them with electrons. Those entangled pairs become the qubits—the basic information units for quantum communication and computing.

“The photons spin in a corkscrew fashion, but more importantly, we can use these spinning photons to impart spin on electrons that are the heart of quantum computing,” said Feng Pan, a postdoctoral scholar and the study’s lead author.

Pan and Dionne are careful not to oversell what they’ve done. Getting from a lab prototype to actual quantum networks will require new light sources, better detectors, and figuring out how to link multiple devices together. Still, the work gives quantum engineers a new foundation to build on—one that doesn’t require a walk-in freezer.

Dionne’s group is focused on miniaturization now. “If we can do that, maybe someday we could do quantum computing in a cell phone,” Pan said. He figures that’s at least a decade out, maybe more.

The real test will be whether the approach holds up as devices get more complex. But for quantum technology, just getting something to work at room temperature is already notable.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!