In mock-ups of the female reproductive tract, bull sperm cluster in groups of two to four, which seems to help them swim upstream

Life

22 September 2022

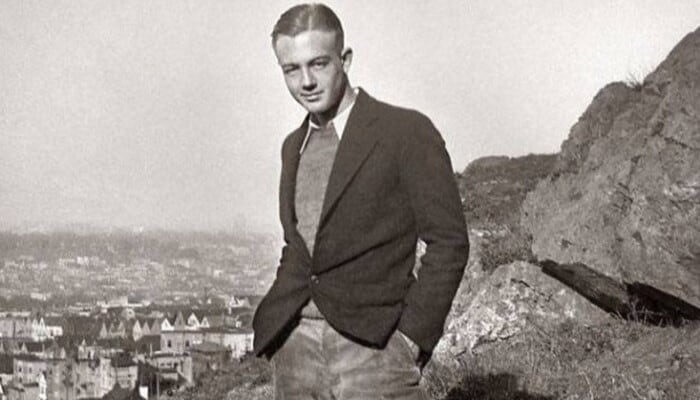

Bull sperm viewed under a microscope, with clusters circled S Phuyal, SS Suarez, C-K Tung

Swimming together in a pack may help sperm to push upstream through thick vaginal and uterine mucus that would wash away those swimming alone.

Sperm have often been represented as individuals racing against each other to fertilise an egg, but these portrayals have been based on flat views of microscope slides and other laboratory settings that don’t reflect their natural context, says Chih-Kuan Tung at North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University.

When placed in a three-dimensional mock-up of the female reproductive tract, bull sperm – which are similar to human sperm – appear to team up in groups of two to four cells.

When Tung and his team first noticed this clustering in their laboratory, they couldn’t understand why it was happening. “In biology, when [cells and structures] do something, they should probably get something out of it,” says Tung. “So that became the question we were asking ourselves: what are these sperm getting out of it?”

To resolve the mystery, the researchers injected 100 million fresh bull sperm into a silicone tube containing fluid that resembled cows’ cervical and uterine mucus – which has the consistency of melted cheese, says Tung. Then, they used a syringe pump to create two speeds of flow.

When there was no flow, the clustered sperm swam in a straighter line than the individual sperm. In an intermediate flow, the clusters could swim upstream, whereas individual sperm couldn’t. When the flow was strong, the clustered sperm pushed through the oncoming current far better than individual sperm – which usually got swept away by the thick stream.

In all these scenarios, there was never one “leader” sperm that was being supported by others in the cluster, says Tung. Rather, the groups were very dynamic, with individual sperm regularly joining and leaving their cluster and changing positions within it. The arrangement resembles how cyclists ride together in a peloton so they encounter less air resistance.

“It could be this kind of mechanism that just allows that at least some of them will eventually get to the oviducts,” says Tung. “Because without this, maybe none of them actually could, because of the strong flow of uterine fluids.”

The clusters probably serve an important role in the thick outflowing mucus in the vagina and cervix as well as in the uterus, where contractions push fluids in multiple directions, he says. Beyond that point, as the sperm reach the oviducts where fluids are thinner and less mobile, it is possible that they start swimming more individually.

The findings open new avenues for helping diagnose unexplained infertility, says Tung. Future analyses may include tests to see how well sperm cluster or to gauge the quality of female reproductive fluids.

Journal reference: Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology , DOI: 10.3389/fcell.2022.961623

More on these topics: