Space elevators are often dismissed as a science fiction dream, but I believe they will exist soon—perhaps in two or three decades. Throughout my career as an aerospace engineer and physics professor, I keep coming back to the concept of a cable stretching from Earth to space, along which people and cargo can easily travel. In recent years I and other researchers have found new ways to tinker with designs and answer questions about how space elevators could work.

There are many reasons to build a space elevator. The obvious one is the major energy and cost savings; it’s a much more practical way to get to orbit than rockets. Another reason that is often overlooked is accessibility. The word “space mission” would be replaced by “transit,” as trips to space become routine and mostly independent of weather conditions. Transits involving humans would be safer than current practices, whereby astronauts must accept a nonnegligible risk to their lives with each launch. A space elevator becomes a bridge to the entire solar system. Release a payload in the lower portion, and you orbit Earth, but do so in the upper portion, and you orbit the sun; all without fuel.

Although I may come across as a space elevator advocate, the truth is, I simply enjoy studying their mechanics. In a world with monumental problems, dreaming of such projects allows me to envision a scenario where we have become responsible custodians on this planet.

My story begins in 2004, when I was a master’s degree student sitting in the office of Professor Arun Misra, hoping he would supervise my thesis. Misra was the leading space expert in the mechanical engineering department at McGill University, so I was more than a little intimidated. The conversation went something like this:

Me: What kind of research do you think I might do?

Misra: Have you ever heard of a space elevator?

Me: No. What is it?

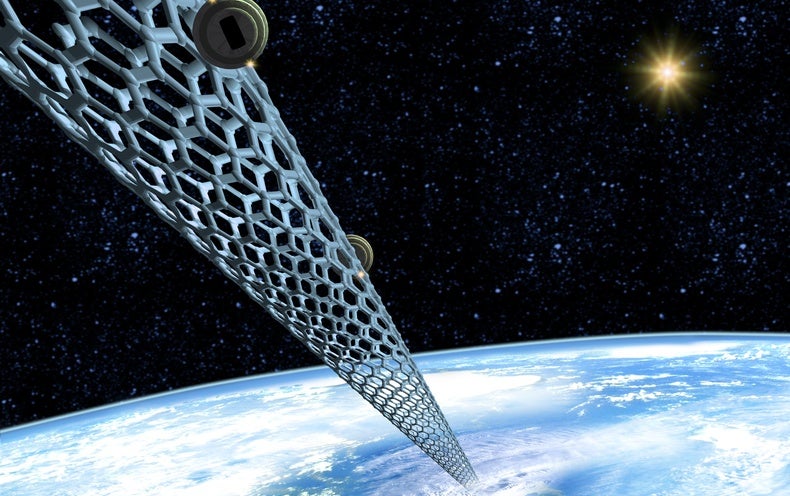

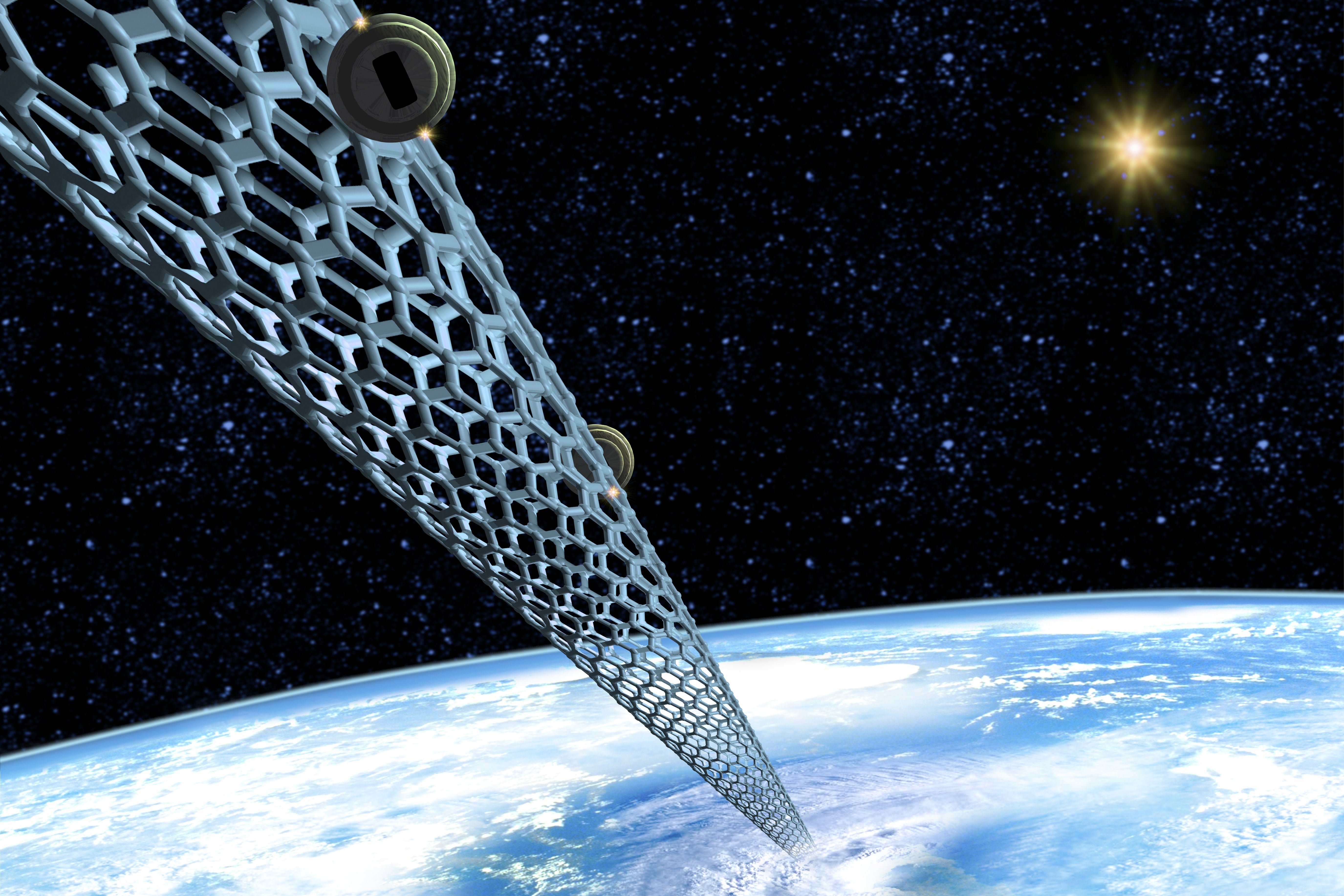

Misra: Imagine a 100,000-kilometer-long cable that extends up from Earth’s equator and is fixed to a satellite at the far end. The system spins along with the Earth. Climbers can scale the cable transporting payloads and then releasing them in space. I was thinking you might study the dynamics of this system.

Me: That sounds … hard.

Misra: Your work will not be hard. Building an actual space elevator here on Earth….

That will be hard.

Flash forward a few years. I had recently published my master’s thesis, entitled The Dynamics of a Space Elevator. I was now working as an engineer in satellite design. While out on the weekend, my friend introduced me to his buddy Colin as “the space elevator guy.” My wife rolled her eyes. I explained to Colin how a space elevator could work.

Me: If you stood on the equator and stared up at a satellite in a geosynchronous orbit (approximately 36,000 kilometers in altitude), it would appear fixed in space, rotating unconnected around the Earth once per day because its speed is just right. Now, that satellite drops a cable to Earth, while simultaneously using fuel to ascend higher. The cable is fastened on the Earth end as the satellite reaches just the right altitude, and the system still rotates along with the Earth. The cable becomes the track that mechanical climbers scale like trains on a vertical railroad, delivering payloads to space.

Colin: But what keeps the cable taut?

Me: A combination of gravitational and centrifugal effects, which compete with one another, and vary along the length of the cable. Below geosynchronous orbit, gravity wins, and beyond it, centrifugal effects win. The result is tension throughout, with a maximum amount exactly at geosynchronous orbit.

Colin: It’s Friday night. Use smaller words.

Me: To build it, we need a material whose specific strength is about 50 times higher than steel. But, in the meantime, me and a handful of other people in the world are pretending that this problem will be solved and tackling other engineering aspects of space elevators while we wait.

Colin: Rad.

My wife and I crossed paths with Colin again in 2014. “How is that space elevator going?” he asked. My wife closed her eyes, her face saying, “Please, no.”

Colin: What I don’t get is why doesn’t the whole cable get yanked down when a climber is loaded onto it at the bottom?

Me: If a climber is situated below GEO, particularly near Earth, the tip of the cable moves down by some small amount, and the tension profile along the cable changes. The real issue is that the portion of cable between the climber and the Earth experiences a drop in tension (like if you held an elastic band vertically in tension, and then affixed a mass halfway along it). If the tension were to drop to zero, the cable would no longer be taut, and the structure would lose its inherent stability. It turns out that a climber (and anything it carries) could have a maximum mass that’s about 1 percent of the total cable mass. This is still a lot of mass, because the cable is expected to be hundreds of tonnes.

Colin: How is that cable material coming along?

Me: I’ve told you, that’s not my thing.

Colin: Get on it, man!

It is now 2022. I was recently presenting a summary of my nearly two decades of occasional work on space elevators in a seminar at Vanier College, where I teach physics. The talk ends and the Q&A portion begins.

Student 1: When will the material for building the elevator be ready?

Me: While the synthesis of potentially suitable materials has progressed in recent years, we are still at least 10 years away from a material solution (one having adequate properties, and that can be manufactured reasonably quickly at a reasonable cost). It’s not unusual for new technologies to await better material science, and fortunately, materials research marches on for reasons unrelated to space elevators.

Student 2: It sounds really cool. But why should we build it?

Me: When you think about it, rockets as a means of transportation are preposterous. For a typical space mission, upwards of 90 percent of the total mass on the launchpad is the fuel! It’s like being in a car with no motor, just a pressurized 100,000-liter fuel tank. We need to replace this inefficient method of escaping Earth’s gravity with a greener road to space.

NASA plans to get humans to Mars before 2040. I suspect that people will indeed walk on Mars (at a cost of hundreds of billions of dollars) before we have an operational space elevator, but for this to be a sustainable endeavor, we’ll need an infrastructure like a space elevator, and better sooner than later.

Student 3: So, when do you think one will be built?

Me: Famed author and engineer Arthur C. Clarke, whose novel The Fountains of Paradise chronicles the building of the first space elevator, was asked this question in the early 1990s. His famous reply was, “Probably about 50 years after everyone quits laughing.” A more modern-day answer might be, “We’ll know we are close when Elon Musk starts taking credit for it.”

Today, I feel much like I did as I sat nervously in Arun’s (yes, we still work together, and I now call him that, and it will always be a bit weird) office. This elegant avenue to space captures my imagination and fills me with hope.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.