RSV is surging—antibody shots and vaccines can protect babies

Cases of respiratory syncytial virus are increasing, but vaccines and antibody shots can keep young children out of the hospital

Nirsevimab (Beyfortus) is one of two available RSV monoclonal antibody shots in the U.S.

FRED TANNEAU/AFP via Getty Images

Winter illnesses are slamming the U.S. A mutant influenza variant is sending scores of people to hospitals, 32 children have died from flu so far this season, whooping cough has killed more than a dozen people, and now respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is surging.

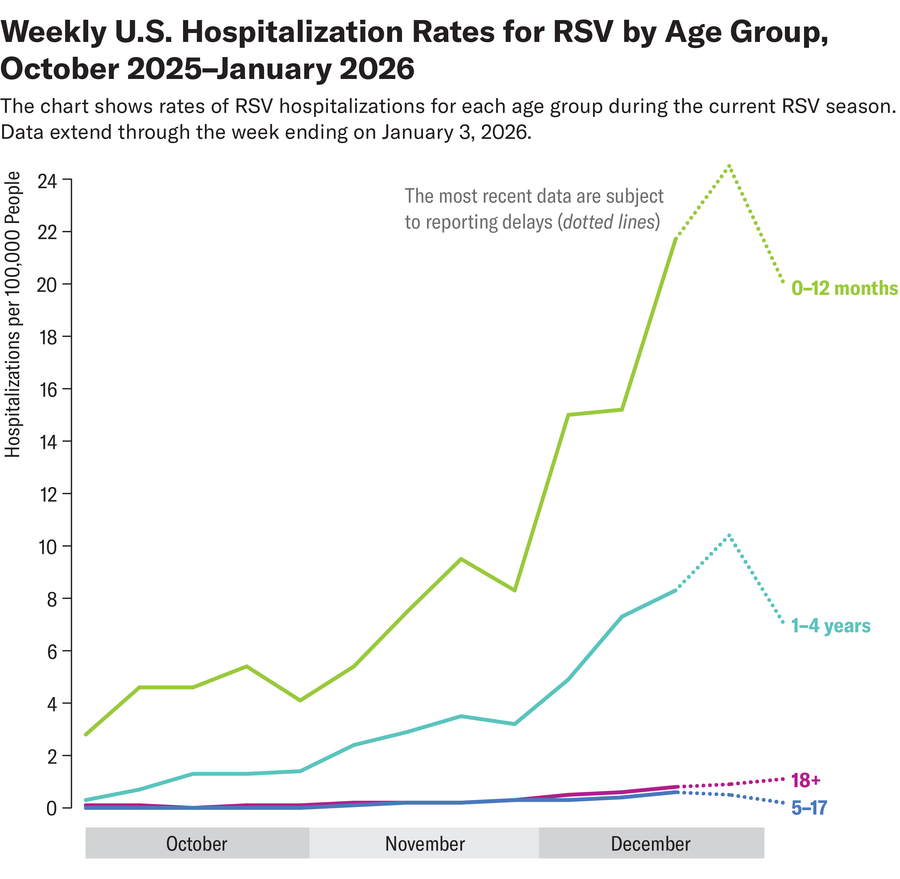

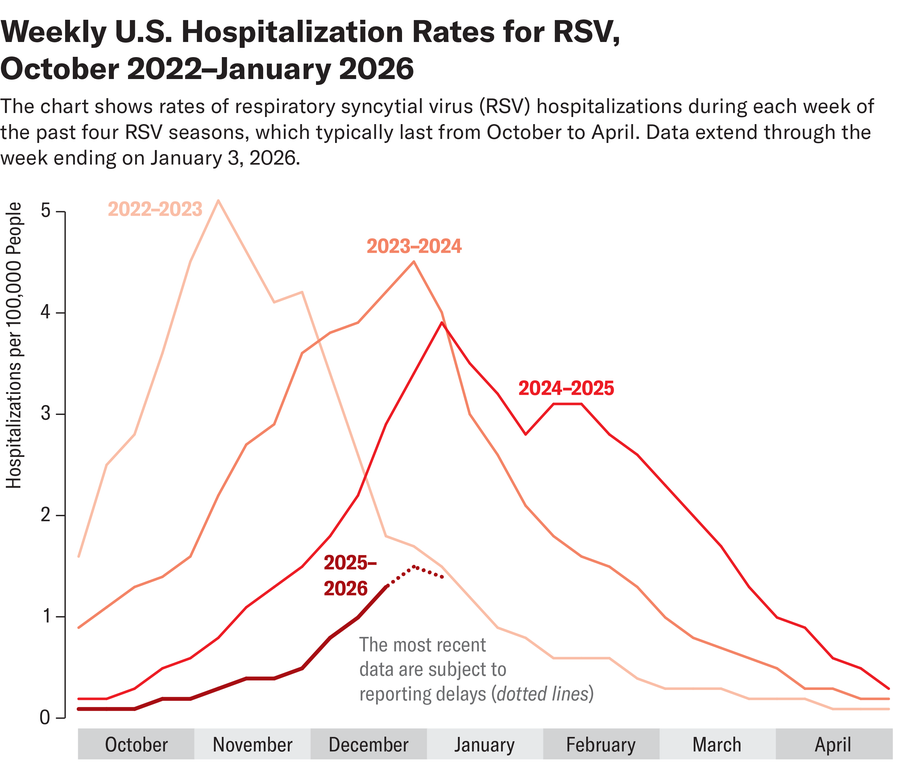

RSV season in the U.S. typically peaks in January and February, with cases often stretching well into March. National emergency room visits and hospitalizations from the virus in kids ages four and younger have dipped slightly but are growing overall in more than a dozen states, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest report on January 16. Overall RSV activity is climbing in many regions; national wastewater surveillance sites—which can forecast future waves of infection in communities—have detected the virus at high concentrations.

“RSV is a really big problem, but we have really effective interventions,” says Yvonne Maldonado, a pediatrician at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

New studies that show RSV vaccination during pregnancy and doses of protective antibodies given to babies in the first eight months of life are both highly effective at preventing severe illness in infants. That protection may even last beyond one RSV season. But the CDC is currently reporting suboptimal RSV vaccination coverage for children and adults—and experts worry those rates will continue to suffer given recent reductions in childhood vaccine recommendations overall. Plus, unfounded doubts about RSV immunization fueled by Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., may set the stage for a more dangerous RSV season.

Nearly everyone gets infected with RSV at some point in their lives. For most healthy individuals, it causes a bad cough, runny nose or fever. The virus can also cause severe illness and long-term complications in older adults. And infections can be particularly life-threatening for young children: the virus is the number one cause of hospitalizations for infants in the U.S.—with the highest risk during the first two months of life. In babies, RSV can cause severe lung infection, or pneumonia, and, in extreme cases, death.

“RSV is a virus that causes the body to secrete a lot of mucus that can get trapped in those tiny airways of little babies and cause a lot of problems with breathing,” says Ruth Karron, a pediatrician and director of the Johns Hopkins Vaccine Initiative. “Kids who are otherwise healthy can actually wind up requiring ventilator support. It’s a really serious disease.”

Luckily, in 2023 two very effective tools became available in the U.S. that protect newborns, who lack fully developed immune systems, from RSV during the early months of life. The vaccine for pregnant people—which is recommended, during the RSV season, to be given between 32 and 36 weeks’ gestation—boosts antibodies to the virus that transfer to the fetus via the placenta. These antibodies target a surface protein on the virus, stopping it from binding to human cells.

If a pregnant person doesn’t get the vaccine or isn’t eligible during RSV season, babies can receive protective antibodies directly through monoclonal antibody shots in the first months of life. These shots are not vaccines. One dose of either of the two available monoclonal shots, nirsevimab (Beyfortus) or clesrovimab (Enflonsia), is recommended for infants eight months and younger—and should be given right before RSV season to ensure protection lasts throughout the months the virus is most active. A second dose may be given to older, higher-risk children, such as those who were born premature.

“Babies who get either the vaccine or the monoclonal antibody can be protected against RSV for as long as six months and potentially longer,” Maldonado says.

Both options are highly effective and safe, but recent studies suggest that the monoclonal antibodies might have some additional benefits over vaccination.

A large recent study in France found that the antibody shot nirsevimab was associated with a lower risk of hospitalization and severe complications from RSV than the vaccine given in utero. That difference became more apparent in later follow-ups, beyond the first month of life, says pharmacoepidemiologist Marie Joelle Jabagi, lead author of the study. “This suggests that duration and timing of protection may play an important role in real-world effectiveness, particularly during a full RSV season,” she says.

One explanation for the results could be because nirsevimab provides direct, immediate immunity to the infant and relatively uniform antibody levels. By contrast, protection from the vaccine depends on the timing of vaccination and how efficiently the antibodies transfer across the placenta, Jabagi says.

Another study published last week found that nirsevimab reduced first-time RSV hospitalizations in infants in Spain by 86 percent during the 2023–2024 season. The data also suggest that protection in some babies even lasted into the following season.

Experts emphasize, however, that even if these recent studies show that nirsevimab may offer greater and longer-lasting protection, the vaccine for pregnant people is still a very effective tool for preventing severe RSV. “I think all these products are phenomenal,” Karron says. “If they are used appropriately, they could really have a huge impact on RSV hospitalization.”

That impact is already being felt in the U.S.: in the 2024–2025 season—the first season after both the vaccine and nirsevimab became available—RSV hospitalization rates dropped as much as 43 percent in children aged zero to seven months old. But experts fear this momentum could sputter under the Trump administration’s recent rehaul of the childhood vaccine schedule. The recommendations for the maternal RSV vaccine and monoclonal antibody doses technically remain unchanged but place a greater emphasis on high-risk infants. Karron worries the language may confuse some parents.

“If you have a full-term healthy baby, you don’t think of that baby as a high-risk child. If you’re reading this and it says ‘only high-risk children,’ it’s an incredible deterrent,” she says. “We really hope that these products continue to be used so that we can keep kids healthy.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.