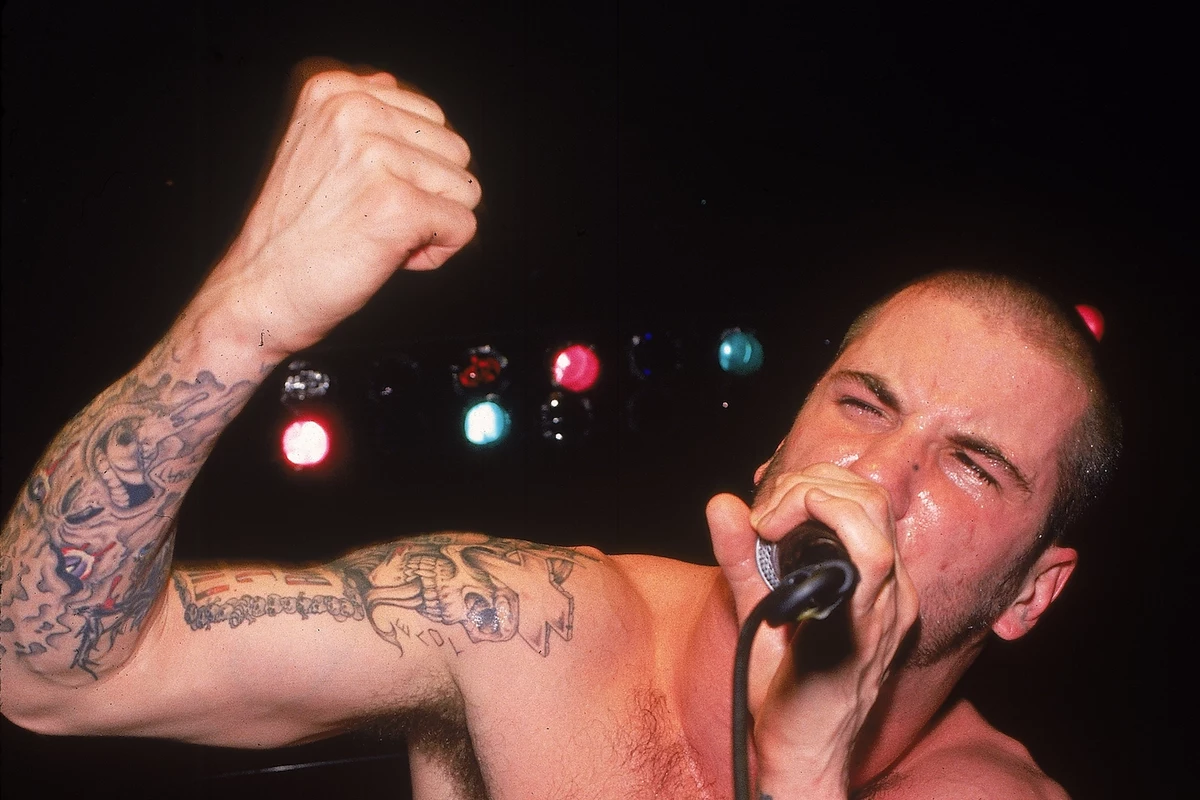

People cool off at a fountain during a heatwave in Athens, Greece, in July 2023

Nicolas Koutsokostas/Shutterstock

As the world warms beyond 1.5°C, large parts of the world will start to have heatwaves so extreme that healthy young people could die within several hours if they fail to find respite, a study has warned. This could result in mass deaths in places where people and buildings aren’t adapted to extreme heat and air conditioning is rare, says Carter Powis at the University of Oxford.

“You could have a very extreme heatwave that departs from historical norms substantially, crosses this threshold and causes much more mortality than you would otherwise expect,” he says. “What we [will] see, particularly in Europe and North America, is an enormous increase in the incidence of these heatwaves [as the world warms] between 1.5 and 2 degrees [C].”

Global warming is already sparking more intense and more frequent heatwaves, so is causing large numbers of fatalities. It is estimated that there were 62,000 heat-related deaths across Europe in the summer of 2022, for instance. However, the vast majority of these were people aged over 65 who may have had existing health issues.

Could global warming result in parts of the world getting so hot that even healthy young people die? Matthew Huber at Purdue University, Indiana, and his colleagues set out to investigate this question in 2010.

Based on theory, they decided the limit of survivability is when the temperature measured by a thermometer covered in a wet cloth exceeds 35°C (95°F). This is the so-called wet-bulb temperature. It reflects the fact that humidity affects our ability to stay cool by sweating. At this wet-bulb reading we can no longer keep core body temperature in check naturally and it will rise to deadly levels if we don’t take action to stay cool in other ways.

At present, the wet bulb temperature very seldom exceeds 31°C (88°F) anywhere on Earth’s surface. Huber’s team concluded that large areas would only start to exceed the 35°C wet bulb limit if the world warmed by more than 7°C – which is thought highly unlikely.

However, recent studies suggest parts of the tropics could exceed this limit at lower levels of warming. What’s more, in practice most people couldn’t survive anything close to a wet-bulb temperature of 35°C. “The original 35-degree limit was meant always as an upper limit,” says Huber.

Last year, Daniel Vecellio at Pennsylvania State University and his colleagues tested 24 healthy young women and men to see how hot and humid it could get before their bodies were unable to stop their core temperature rising – the point at which heat is “noncompensable”. Continued exposure to these conditions for several hours can result in death.

The findings suggest the survivability limit is closer to a 31°C wet-bulb reading, though other factors will affect this in reality. Because the volunteers weren’t acclimatised to heat and were doing everyday tasks during the tests, this should be seen as a lower limit with a 35°C wet-bulb temperature being the upper limit, says Powis.

“Anything between those two is very much in the danger zone,” he says. “There’s not just one threshold that is relevant to everyone. Different populations have different thresholds where there could suddenly be dramatic mortality outcomes.”

Powis and his colleagues have now used data from weather stations and climate models to see where in the world such conditions may currently occur based on Vecellio’s 31°C wet-bulb findings, and how this will change at the world warms.

For instance, with 1°C of global warming – a level already passed – only 3 per cent of weather stations in Europe are likely to pass Vecellio’s threshold more than once in 100 years. With 2°C of warming, 25 per cent are likely to. In the US, 20 per cent of stations are likely to pass the threshold more than once in 100 years with 1°C global warming, rising to 28 per cent for 2°C.

“Sometimes these human survivability limits are useful to understand the problem, but the reality is that we see a significant health burden on the population even at ‘moderate’ temperatures,” says Dann Mitchell at the University of Bristol, UK, who wasn’t involved in the study. “Using a threshold-based temperature can be misleading, because even if it’s hot outside, it doesn’t mean that it’s hot inside.”

“I would like to highlight that all heat-related impacts on human health and well-being are preventable,” says Raquel Nunes at the University of Warwick in the UK. But with heatwaves becoming more frequent, more intense and more prolonged, urgent action is needed to prevent more heat-related deaths, she says.

Topics: