Enzymes made by gut bacteria in larvae of the beetle Zophobas morio can degrade polystyrene used in packaging, and could help recycle plastics

Environment

9 June 2022

Enzymes produced by gut bacteria in larvae of the beetle Zophobas morio can digest polystyrene. The enzymes could be adapted to degrade plastic in recycling plants.

A previous study had found that another type of beetle larvae can eat and digest the expanded polystyrene used in packaging thanks to the action of Serratia fonticola bacteria in their guts.

Now, researchers have identified polystyrene-degrading bacterial species in the guts of Z. morio larvae – which are known as “superworms” because of their size.

“We are the first ones to use a high-resolution method [to identify] potential polystyrene-degrading enzymes in the microbes of the superworm guts. We could also identify the bacterial lineages that possess these polystyrene-degrading capabilities,” says Christian Rinke at the University of Queensland, Australia.

Rinke and his colleagues found that the main polystyrene-digesting bacterial species included Pseudomonas aeruginosa and species belonging to the Rhodococcus, Corynebacterium and Sphingobacterium groups.

They found that these microbes produced a class of enzymes called hydrolases that use water to degrade the plastic polymer into styrene monomers, which are then broken down inside bacterial cells.

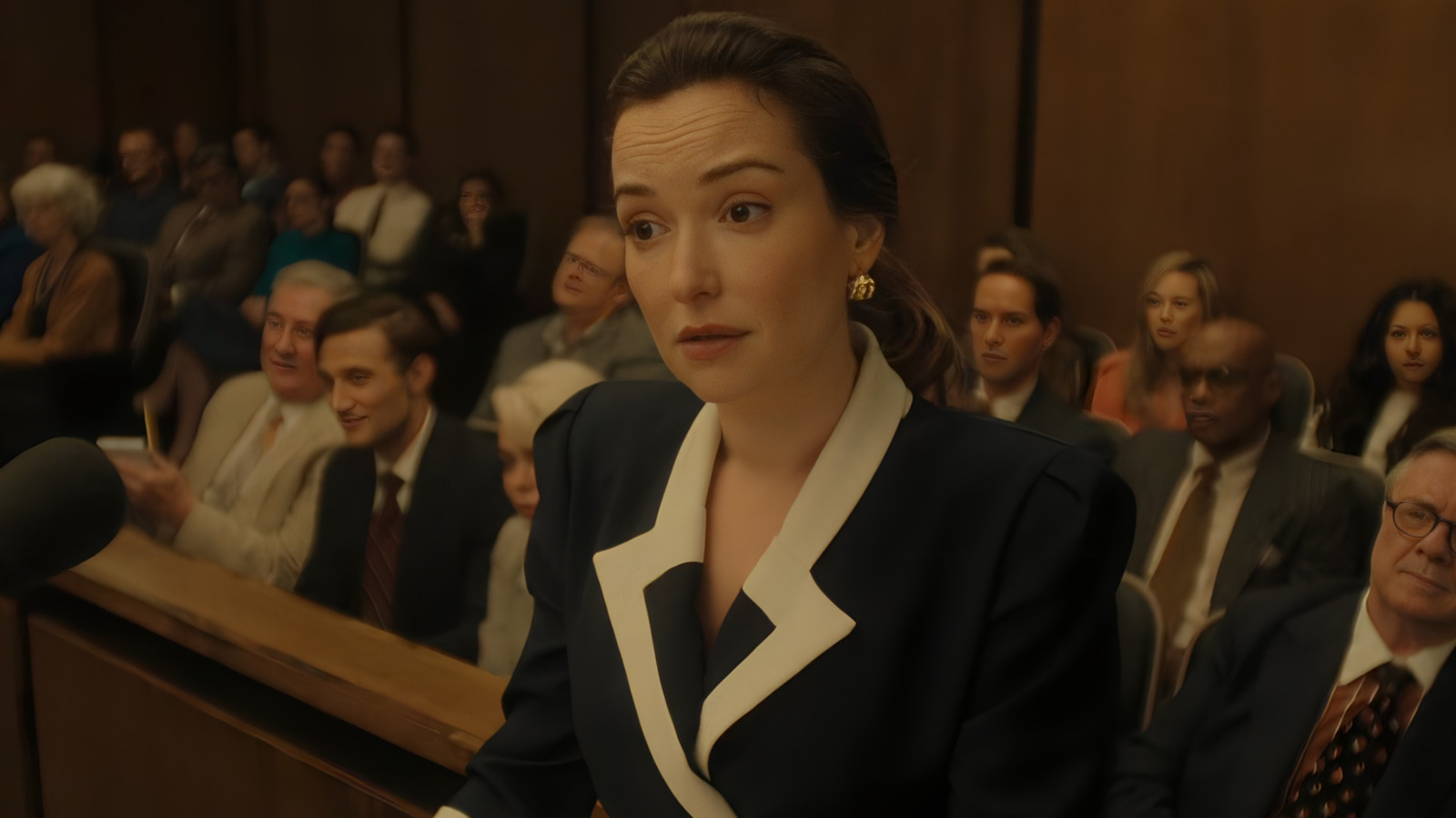

The common Zophobas morio “superworm” can eat polystyrene The University of Queensland

The team divided 171 superworms into three groups that were each fed either wheat bran, polystyrene or no food at all for three weeks. The researchers found that the worms began to chew their way into blocks of polystyrene within a day.

“We confirmed that superworms can survive on a solely polystyrene diet and even gain a small amount of weight compared to a starvation control group, which suggests that the worms can gain energy from eating polystyrene,” says Rinke. “The polystyrene-reared superworms even completed the entire life cycle, formed pupae and emerged as adult beetles.”

However, the polystyrene-eating superworms put on less than a quarter of the weight gained by larvae that ate bran, suggesting eating plastic comes at a cost to their health.

“A possible way to work with the superworms is to provide food waste or agricultural bioproducts with the polystyrene. This could be a way to improve the health of the worms and to deal with the large amount of food waste in Western countries,” says Rinke.

But the researchers are more interested in creating a superworm-free system that takes inspiration from the insects.

“We will focus on creating a system that mimics the mechanical degradation of plastic by the superworm, followed by further degradation by bacterial enzymes… into metabolites that can then be used by other microbes to produce chemical compounds of higher value, such as the bioplastic polyhydroxyalkanoate,” says Rinke.

“This work is a useful supplement to the research on the degradation of plastics by insect gut microbes and enzymes,” says Jun Yang at Beihang University in China. Nevertheless, further work to tweak the enzymes and optimise the composition of microbial communities for efficient plastic degradation will be needed before application, adds Yang.

“It is still too early to make any predictions about when a bioprocess for polystyrene recycling will be available. It will take time to isolate and characterise these enzymes… and then engineer them to meet the stringent requirements for developing a bio-based recycling process,” says Ren Wei at the University of Greifswald, Germany.

Journal reference: Microbial Genomics, DOI: 10.1099/mgen.0.000842

More on these topics:

.jpg)

![[Spoiler] Dies in Season 7, Episode 5 — Recap [Spoiler] Dies in Season 7, Episode 5 — Recap](https://washingtonweeklytimes.com/wp-content/themes/jnews/assets/img/jeg-empty.png)