The novel antiviral drug Paxlovid swiftly entered the U.S. pharmaceutical market in late 2021 as an emergency treatment for people who were vulnerable to severe COVID complications. By May 2023, when the Food and Drug Administration fully approved the oral medication, more than 11.6 million treatment courses had been prescribed, making Paxlovid a go-to regimen for easing COVID symptoms even in people who were only mildly or moderately sick.

But a new study published in the New England Journal of Medicine last week found that Paxlovid (a combination of the drugs nirmatrelvir and ritonavir) may not be as effective at fending off COVID symptoms in some people as scientists and physicians previously hoped. In the study, researchers at the biomedical company Pfizer, which developed Paxlovid, assessed participants enrolled in a phase 2-3 trial. They found that both vaccinated people with a high underlying risk for severe infection and unvaccinated people with a low risk for severe infection experienced COVID symptoms for roughly the same duration regardless of whether they took Paxlovid.

The medication is still beneficial to some people—especially older or immunocompromised people who are at a high risk of hospitalization from COVID. But the findings suggest that the medication does not relieve symptoms for those whose risk of severe infection is low or moderate. “I think the reason why the FDA approved Paxlovid and why guidelines committees have recommended it is because of the evidence from previous studies about its benefits to high-risk unvaccinated people,” says Rajesh Gandhi, an infectious disease physician at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, who recently published a commentary on the new research but was not involved in the study. Paxlovid has been crucial for treating COVID, yet more effective options are needed, he says.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Lead study author Jennifer Hammond, vice president of global product development at Pfizer, says that this investigation is the first major clinical trial of Paxlovid since the creation and distribution of COVID vaccines. She adds that previous research suggesting that Paxlovid is largely effective at preventing hospitalization in high-risk unvaccinated people still holds. The recent study could not make conclusions for these high-risk individuals because most of the trial’s participants were under the age of 65, with a low to moderate risk for developing severe COVID. “We are looking at how we can apply these learnings from this new study to future [drug] development programs,” Hammond says. “The field still has a lot of learning to do about how to accurately assess symptom alleviation and resolution.”

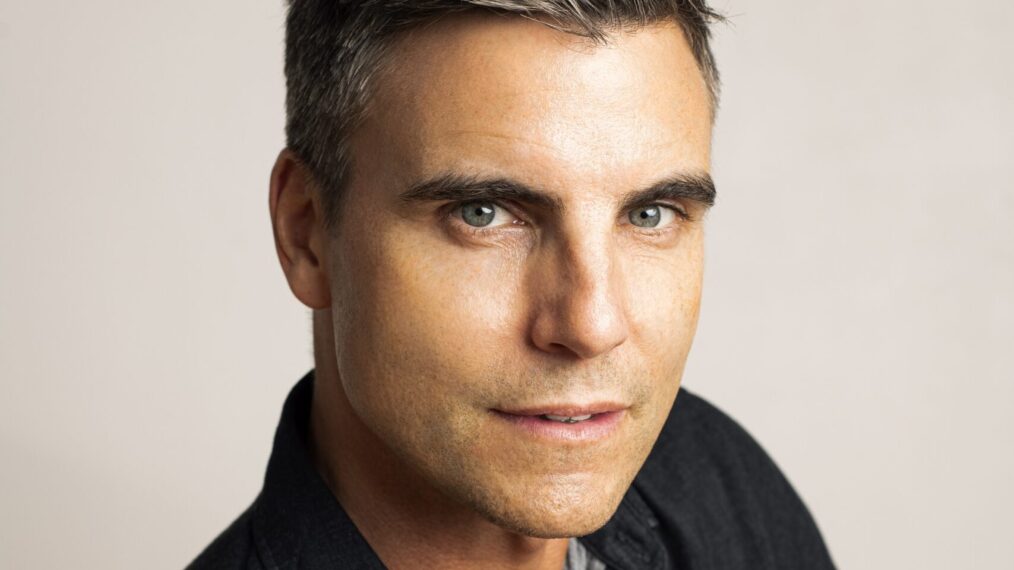

Scientific American spoke with Gandhi about who will still benefit from taking Paxlovid, the significance of this study and ongoing research on alternative COVID treatments.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

What did scientists previously know about Paxlovid’s efficacy?

What we knew about Paxlovid was mainly based on a randomized controlled trial called the EPIC-HR [Evaluation of Protease Inhibition for COVID-19 in High-Risk Patients] study. It was done two years ago and studied people who were unvaccinated and had a high risk of COVID complications, meaning they had some other [preexisting] condition that elevated their chances of hospitalization. In the study, it was found that people who got Paxlovid, compared with people who got the placebo, had an 88 percent reduction in their progression of going to the hospital or a doctor. This is what got Paxlovid approved in the U.S.

Since the development of COVID vaccines, some observational studies have suggested that Paxlovid is also beneficial to vaccinated people with a high risk for severe infection. Yet the latest results suggest otherwise. What makes this new study’s findings more conclusive?

Observational studies are important, but they aren’t necessarily definitive in the way that a randomized study is. In observational studies, researchers follow very, very large numbers of people who either did get the medication or didn’t. This means, though, that they have to consider outside factors—or confounding factors—that might [affect their results]. For instance, if a physician happens to be worried about a particular patient, they may be more likely to give them Paxlovid. Another example is age, which is a very strong risk factor for developing a COVID complication. It wouldn’t be fair to compare 70-year-olds who got Paxlovid with 30-year-olds who didn’t, right? So researchers need to [mathematically] adjust for this. And even still, everyone worries about variables that they never realized were systematically different about the people in their study that skewed the findings.

The beauty of a randomized study is that it’s literally like flipping a coin. You know that the people who get either the placebo or Paxlovid really are comparable because it’s completely randomly assigned.

What do the results of this new study suggest about the medication’s efficacy?

This study evaluated two groups: unvaccinated people with a low risk of COVID complications and vaccinated people with a high risk of COVID complications. There were about 1,300 people enrolled—making it a moderately sized study—and half of them were randomly assigned Paxlovid, and the other half [were given] a placebo. [The researchers’] primary goal was to look at whether Paxlovid reduced the time it took for participants’ symptoms to [resolve]. They found, overall, that both groups had similar durations of symptoms.

It’s Important to note, though, that only about 5 percent of the participants in this study were [aged 65 or older], and we know that older age is one of the strongest [risk] factors for COVID complications. They also had only a small group of people who were severely immunocompromised or had heart or lung disease, which are other big risk factors for complications. It’s hard, then, to make conclusions about Paxlovid in vaccinated high-risk people because there were relatively few in this study.

Why do you think so few people who were aged 65 or older or who were immunocompromised were included?

I’m not entirely sure, but there are a lot of real-life considerations people make when they’re deciding to enroll [in a study]. The risk of hospitalization and death [from COVID] has also gotten lower over time, thankfully, and it takes involving more and more people to accurately evaluate Paxlovid and other developing COVID treatments. [Editor’s Note: In an e-mail to Scientific American, Kit Longley, a spokesperson for Pfizer, said that the researchers enrolled more participants who were younger than age 65 with no comorbidities to provide a contrast with the participants in the previous study, EPIC-HR, who were exclusively older or immunocompromised.]

Who would still benefit from taking Paxlovid?

Many of my colleagues and I do think that despite this new study, there is still a role for Paxlovid in particularly high-risk individuals, even if they’ve been vaccinated. If someone is more than 65 years old or has severe heart disease, lung disease or a condition that makes them immunocompromised, I do still recommend that they get Paxlovid.

Paxlovid can interact with some medications when taken together with them. Which medications are most concerning?

One very commonly used drug that can interact with Paxlovid is a statin that is used to lower cholesterol and prevent heart disease. Tens of millions of people in the U.S. are on statins, and it’s their only medicine. Thankfully, it is safe to stop [some types of statins] for the [five] days one is on Paxlovid and the three days following, as the effects are wearing off. [Editor’s Note: Hammond, the study’s lead author, told Scientific American that people who are considering taking Paxlovid and are on additional medications should consult a physician about any risks for interactions.]

Immunosuppressant medications, on the other hand, are tricky to dose with Paxlovid, and you really don’t want to stop them. People who’ve had a recent organ transplant often take [immunosuppressants], and you wouldn’t want to stop them and risk an organ rejection. We definitely need more research to develop a better COVID drug that doesn’t have that kind of negative interaction.

Is it harmful for a person to take Paxlovid if they are fully vaccinated and have a low to moderate risk of severe disease?

I wouldn’t say there’s an excess risk. I will note, though, that Paxlovid does have short-term side effects. I am one of the people who took it when I had COVID, and it does leave a very bad taste in one’s mouth and can cause nausea. No medicine is 100 percent [perfect], and there’s always some risk that comes with it. If someone with COVID is a completely healthy young person, I definitely don’t see an advantage.

What we don’t quite know yet but hope to know soon is how Paxlovid might help prevent long COVID in people who are considered low or standard risk for COVID complications [Editor’s Note: Another study has found that people with at least one risk factor for severe infection who took Paxlovid had a lower chance of developing long COVID symptoms. Research on Paxlovid’s effects on long COVID is ongoing.]

What future research would you like to see on Paxlovid and other COVID treatments?

Paxlovid is certainly an advancement, and it has a role, but I don’t think it should be where we end. I think that there’s still room and a need for drugs with fewer interactions [with other medications] that are more effective. There is another drug similar to Paxlovid called ensitrelvir that is in clinical trials here but is currently authorized in Japan. We’re hoping to get results for that drug [in the U.S.] sometime later this year. But I’d say, overall, I urge the field to continue to invest in developing new drugs because there’s such an unmet need in people who are still ending up in the hospital with COVID.