A personalised mRNA vaccine for pancreatic cancer has produced promising results in a small initial trial involving people whose cancers were detected early enough to be operated on

Health

8 June 2022

New mRNA vaccines for pancreatic cancer have shown promising results www.alamy.com

Pancreatic cancer is the deadliest of cancers, with few treatment options. Now, an mRNA vaccine treatment, called autogene cevumeran, that is tailored to each individual’s cancer has produced promising results in a small initial trial.

What were the results?

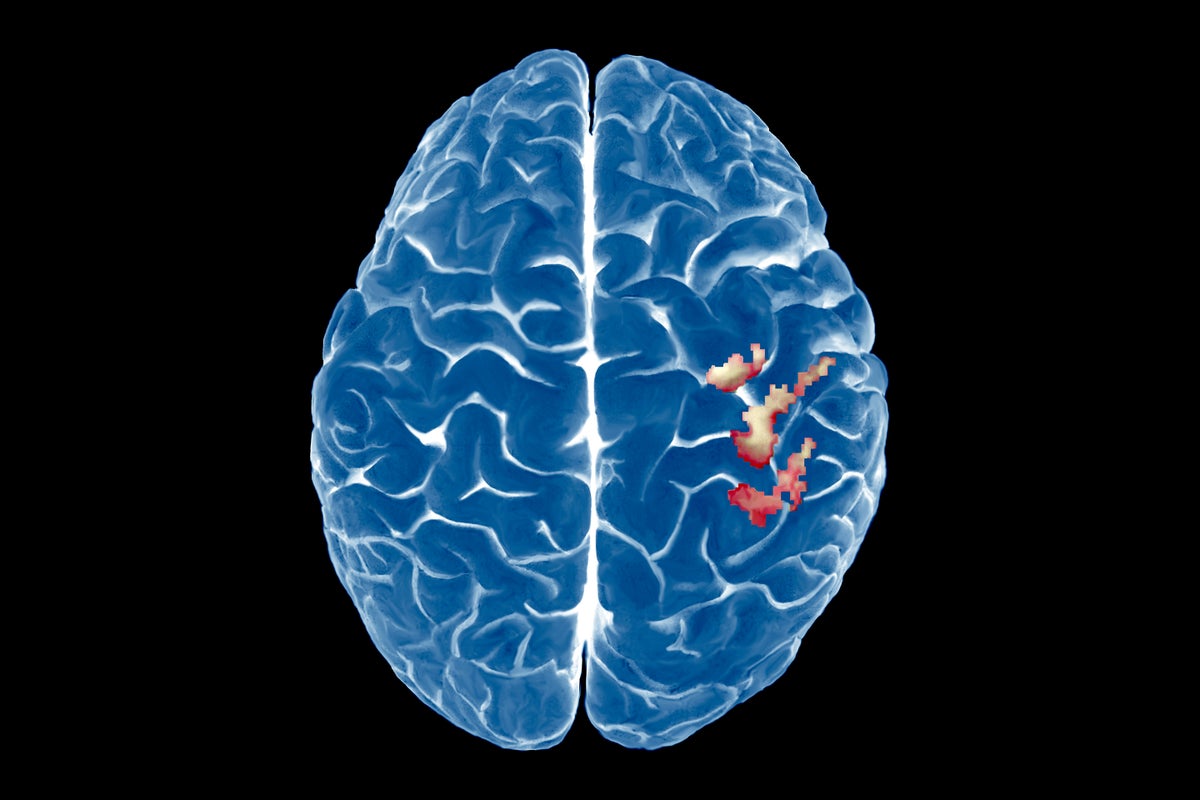

In the trial, 16 people were given the vaccine around nine weeks after having an operation to remove their tumours. In eight, the vaccine didn’t elicit an effective immune response and their cancers returned. But in the other eight, the vaccine resulted in a good response and they remained cancer-free 18 months later. The results were announced by the vaccine’s developer, BioNTech, on 5 June.

Does this mean the vaccine could help up to half of those diagnosed with pancreatic cancer?

Unfortunately not. Firstly, this is a very small initial trial. Larger and longer trials will be needed to confirm the result. Secondly, the trial only involved people whose cancers were detected early enough that they could undergo an operation to remove tumours before they spread to other parts of the body. Only around 10 per cent of people are diagnosed at this stage, says Chris Macdonald, head of research at charity Pancreatic Cancer UK. In other words, even if larger trials confirm these initial results, it remains to be seen if this vaccine can help people with more advanced pancreatic cancer – though that is, of course, the hope.

Why is pancreatic cancer diagnosed late?

The problem is that the symptoms of pancreatic cancer are vague, says Macdonald. By the time it is detected, 70 per cent of people are so ill that it is too late for any treatment.

How does the mRNA vaccine work?

When someone’s tumour is removed, the DNA of the cancer cells is sequenced and compared with healthy cells from the same individual. BioNTech looks for proteins that have mutated in the cancer cells and that therefore distinguish these cells from healthy ones. The company then creates mRNAs – a genetic recipe – coding for up to 20 of these proteins, which are injected into an individual. The aim is to get the immune system to target and destroy any cells producing these proteins. It is the same principle as for the mRNA vaccines against covid-19.

Was the vaccine the only treatment given in the trial?

No. The participants were also given chemotherapy, as is standard after surgery, says Macdonald. In this trial, they also received a drug called atezolizumab, which is a type of PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor. Some cancers tell the immune system not to attack them, and PD-1 inhibitors block that signal.

Will those who responded to the vaccine remain cancer-free?

Only longer follow-ups and larger trials will tell. If some cancer cells survived the combination treatment, they could evolve to resist the immune attack triggered by the vaccine. This is the reason why many tumours initially respond to treatments, but then evolve resistance. “You run the risk with every cancer type,” says Macdonald.

When will this vaccine become more widely available?

That depends on the decisions of BioNTech and regulatory authorities, so it is impossible to say. Because the survival rates for pancreatic cancer are so low, however, regulators are likely to accelerate the approval process if larger trials are successful.

Is this the first mRNA vaccine against cancer?

No, far from it. Researchers have been using the mRNA approach to try to treat cancer since at least 2008. The results have been mixed, but the technology is improving and the success of the mRNA covid-19 vaccines has given the field a big boost. As yet, no mRNA-based cancer vaccine has been approved, but many trials are currently under way or planned.

Are there other kinds of cancer vaccine besides mRNA ones?

Yes, lots of them. Many different approaches are being tested and a few cancer vaccines have already been approved. For instance, sipuleucel-T (sold under the brand name Provenge) is a prostate cancer vaccine created by exposing immune cells to a prostate cancer-linked protein and then injecting those cells back into an individual’s body. There are also several vaccines that prevent cancer by limiting infections by the viruses that cause them, such as the HPV vaccines that are proving extremely effective at preventing cervical cancer-causing infections.

What else could mRNA vaccine technology be used for?

An mRNA vaccine works by making our bodies produce a small quantity of specific proteins. Many highly effective treatments, such as antibodies, are protein-based, but manufacturing proteins is slow and expensive. So if we can use mRNA technology to get our bodies to make large enough quantities of therapeutic proteins, not just vaccines, it could lead to better treatments for a huge range of diseases and disorders.

More on these topics: